The best-known ghost story from ancient Egypt is known, simply, as A Ghost Story but sometimes referenced as Khonsemhab and the Ghost. The story dates from the late New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570 - c.1069 BCE) and specifically the Ramesside Period (1186-1077 BCE).

It was found in fragments on ostraca (pottery with writing on it) which scholars such as Georges Posener (in 1960 CE) and Jurgen von Beckerath (in 1992 CE) claim are copies of a much older story from the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE). This would make sense as the traditional view of the afterlife in Egypt as a paradise was often questioned in texts from that era (such as The Lay of the Harper or A Dispute Between a Man and his Soul), and Khonsemhab reflects this view in his conversation with the ghost.

A Ghost Story tells the tale of the High Priest of Amun Khonsemhab and his encounter with a restless ghost whose tomb has deteriorated. The story exists on four ostraca discovered in and around the necropolis of Deir el-Medina near Thebes between c. 1880 CE and 1905 CE. These ostraca today are housed in museums in Paris, Florence, Vienna, and Turin and each one relates another section of the story. The conclusion of the tale, unfortunately, has not yet been found.

As is the case with ghost stories from around the world, the Khonsemhab tale operates on two levels: entertainment and cultural education. An audience would have been entertained while at the same time receiving instruction on the importance of honoring the dead by caring for their final resting places.

The Story

Scholars differ on interpreting the text. Some claim it is a first-person narration by a speaker who spends the night in the necropolis at Thebes and encounters an angry spirit. This nameless narrator then goes to the high priest to seek his help and Khonsemhab raises the spirit to talk to it. The first-person narrator interpretation rests entirely on one of the early lines. Other scholars claim it is a third-person narration which tells how Khonsemhab encountered the spirit in the necropolis and then dedicated himself to helping it find peace.

The beginning of the story is as fragmentary as the conclusion which breaks off, so it is understandable how one concludes the "I" mentioned at the start indicates first-person narration. The story makes more sense as third-person omniscient narration, however, as no first-person narrator makes an appearance after the opening lines and these lines could, in fact, be dialogue spoken by Khonsemhab. Some translations, in fact, omit the "I" in the opening lines entirely, attributing them to Khonsemhab, without any effect on the story's cohesion.

Either way, after two lines which relate some sort of journey, Khonsemhab returns to his house and calls on the spirit to come to him and identify himself, promising to help him by building a new sepulcher and providing him "with all sorts of good things." It is clear that the high priest is already aware of the spirit's troubles. The ghost appears and says his name is Nebusemekh. Khonsemhab asks the spirit what is troubling him and Nebusemekh replies that his tomb has fallen and no one now remembers where he is buried so that proper offerings are no longer brought. Nebusemekh says he is "exposed in the wintry wind, hungry without food" and fears he may soon cease to exist or, as he puts it, "to overflow like the inundation" and be lost because his soul has no home to contain it.

Khonsemhab sits down next to the spirit and weeps for him in his sad state. The spirit then relates who he was in life:

When I was alive upon the earth I was overseer of the treasury of King Mentuhotep and I was lieutenant of the army, having been at the head of men and nigh to the gods. I went to rest in Year 14, during the summer months, of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Mentuhotep. He gave me my four canopic jars and my sarcophagus of alabaster and he had done for me all that is done for one in my position. He laid me to rest in my tomb with its shaft of ten cubits. See, the ground beneath has deteriorated and dropped away. The wind blows there and seizes the tongue. Now as for your having promised me `I shall have a sepulcher prepared anew for you' I have it four times already that it will be done in accordance with them. But what am I to make of the promises you have just made to me so that all these things may succeed in being executed? (Simpson, 113-114)

Khonsemhab assures the spirit that he will do everything he can for him saying, "Please express to me a fine commission such as is fit to be done for you and I will surely have it done for you," but the spirit is not convinced. Nebusemekh says, "Of what use are the things you would do? Unless a tree is exposed to sunlight, it does not sprout foliage," meaning that he does not expect the priest to be able to provide him with the kind of home he once had as Khonesemhab does not have those kinds of resources; just as a tree cannot blossom without sunlight, his tomb cannot be rebuilt on promises and goodwill. The priest has assured him already that, if he cannot build him a new tomb, he will have five men servants and five maidservants bring him food and water as offerings daily, but the spirit would not be consoled.

Nebusemekh disappears, but Khonsemhab does not forget what he has promised. He sends men to search for the ruined tomb, and they find it "twenty-five cubits distant along the king's causeway at Deir el-Bahri" and return to tell their master. Khonsemhab is pleased with this news and celebrates with the men and, afterwards, summons an official to tell him about the project. The story ends with the line "He returned in the evening to sleep in the Ne and he..." but the rest of the tale is lost. The "Ne" in the line refers to the necropolis at Thebes, and it is thought that Khonsemhab returns to where he was at the beginning of the story to tell Nebusemekh that he will soon have a new home.

The Text

In the course of the tale here, one will find "l.p.h." after a king's name. This is the English equivalent of the Egyptian phrase Ankh wedja seneb, meaning "life, prosperity, health," which appears after royal names in ancient inscriptions. The following text follows Beckerath's translation as reprinted in W.K. Simpson's The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, Stelae, Autobiographies, and Poetry.

It omits the first-person narrator's line from the beginning of the story, "Now while I was looking toward the west, he went up onto the roof" which often appears in translations as the third line below. Ellipses throughout indicate missing words from the story while brackets and parentheses suggest probable words/sentences which are unclear in the original. The text reads:

[...according to] his habit...after the way he had done...He ferried across and reached his house. He caused [offerings to be] prepared saying, "I will provide him with all sorts of good things when I go to the west side." He went up onto the roof and he invoked the gods of the sky and the gods of the earth, southern, northern, western and eastern, and the gods of the underworld, saying to them: "Send me that august spirit." And so he came and said to him: "I am your...who has come to sleep during the night next to his tomb." Then the High Priest of Amun Khonsemhab said to him: "Please tell me your name, your father's name, and your mother's name that I may offer to them and do for them all that has to be done for those in their position." The august spirit then said to him: "Nebusemekh is my name, Ankhmen is my father's name, and Tamshas is my mother's name."

Then the High Priest of Amun-Re, King of the Gods, Khonsemhab said to him; "Tell me what you want that I may have it done for you. And I shall have a sepulcher prepared anew for you and have a coffin of gold and zizyphus-wood made for you, and you shall [rest therein] and I shall have done for you all that is done for one who is in your position."

The august spirit then said to him: "No one can be overheated who is exposed to wintry wind, hungry without food... It is not my desire to overflow like the inundation, not...not seeing my tomb... I would not reach it. There have been made to me promises..."

Now after [he] had finished speaking, the High Priest of Amun-Re, King of the Gods, Khonsemhab, sat down and wept beside him with a face full of tears. And he addressed the spirit, saying, "How badly you fare without eating or drinking, without growing old or becoming young. Without seeing sunlight or inhaling northerly breezes. Darkness is in your sight every day. You do not get up early to leave."

Then the spirit said to him: "When I was alive upon the earth I was overseer of the treasury of King Mentuhotep and I was lieutenant of the army, having been at the head of men and nigh to the gods. I went to rest in Year 14, during the summer months, of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Mentuhotep. He gave me my four canopic jars and my sarcophagus of alabaster and he had done for me all that is done for one in my position. He laid me to rest in my tomb with its shaft of ten cubits. See, the ground beneath has deteriorated and dropped away. The wind blows there and seizes the tongue. Now as for your having promised me `I shall have a sepulcher prepared anew for you' I have it four times already that it will be done in accordance with them. But what am I to make of the promises you have just made to me so that all these things may succeed in being executed?"

Then the High Priest of Amun-Re, King of the Gods, Khonsemhab, said to him: "Please express to me a fine commission such as is fit to be done for you and I will surely have it done for you. Or I will [simply] have five men (servants) and five maid servants, totaling ten, devoted to you in order to pour libation water for you and I will (have) a sack of emmer delivered daily to be offered to you. And also the overseer of offerings shall pour libation water for you."

Then the Spirit of Nebusemekh said to him: "Of what use are the things you would do? Unless a tree is exposed to sunlight, it does not sprout foliage. (But) stone never proceeds to age; it crumbles (only) through..."

...King Nebhepetre, l.p.h., ...there The High Priest of Amun-Re, King of the Gods [commissioned] three men, each one... And he ferried across and went up...The men searched for the tomb near the holy temple of King Nebhepetre, l.p.h. [the Son of Re, Mentuhotep], l.p.h. And they found...in it, it being twenty five cubits distant along the king's causeway at Deir el Bahri.

Then they went back down to the riverbank and they [returned to] the High [Priest] of Amun-Re, King of the Gods, Khonsemhab, and found him officiating in the god's house of the temple of Amun-Re, King of the Gods. And he said to them: "Hopefully you've returned having discovered the excellent place for making the name of that spirit called Nebusemekh endure unto eternity." Then the three of them said to him with one voice: "We have found the excellent place for [making the name of that august spirit endure"]. And so they sat down in his presence and made holiday. His heart became joyful when they told him...until the sun came up from the horizon. Then he summoned the deputy of the estate of Amun Menkau and informed him about his project.

He returned in the evening to spend the night in Ne, and he....

Commentary

As noted, it is assumed that Khonsemhab remained true to his word and the story ended happily for the spirit of Nebusemekh. Simpson notes that the "High Priest Khonsemhab was probably a fictitious character" but that the setting of the necropolis of Thebes would have been familiar to those hearing the story (112). Placing the tale in a familiar setting and choosing a High Priest of Amun as the central character would have made the story more believable and relatable for an ancient Egyptian audience. It would have worked the same way as setting any ghost story in a well-known "spooky" locale in the present day.

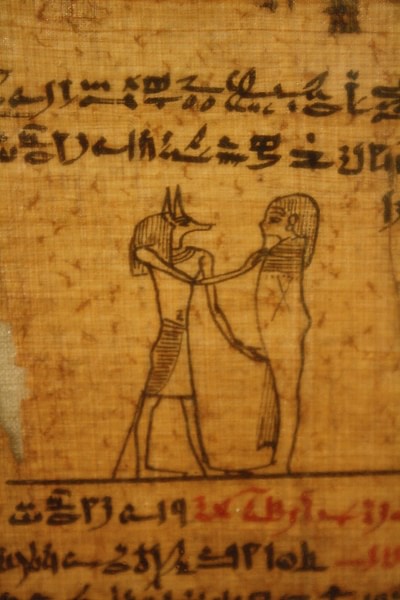

Ghosts were not considered "spooky" in ancient Egypt, however; they were simply a natural part of existence and one which the Egyptians usually took pains to guard against. The mortuary rituals which honored the dead were intended to make sure no one came back from the afterlife dissatisfied at all. The proper rites surrounding death and burial were important in all ancient societies and the Egyptians were no different in this.

Since the afterlife was considered simply a continuation of one's life on earth, and as it was hoped that the spirit of the deceased would be judged favorably by the god Osiris and allowed to pass on to that paradise, there was no reason for a spirit to return to earth unless it was troubled; and that trouble often had to do with either improper observance of burial or the destruction or looting of one's tomb. The tomb was considered the "house of the spirit" and if one's tomb were forgotten, if the proper rites of remembrance were not observed, the spirit would not have peace. The appearance of a ghost, unless summoned for a particular reason or visiting in a dream, was never considered a good sign.

Even so, communication with the dead was sometimes sought for counsel in dealing with problems or making important decisions. The dead were thought to be able to communicate with the living through dreams and certain wise women were consulted as seers to interpret these dreams and foretell the future. According to Egyptologist Rosalie David, these seers operated both within and outside of the temple and funerary cults in efforts to either facilitate a meeting between the living and the dead or interpret a dream concerning the deceased. She writes, "these approaches included the use of oracles and magic, letters to the dead, dreams and other forms of divination" (271). In the case of Khonsemhab, he chooses to summon the ghost directly and speak to it plainly rather than rely on an intermediary and, as a high priest, he would be expected to be able and willing to do this.

In this story, the ghost of Nebusemekh is not presented as scary but as a soul in need of help. The story emphasizes the importance of regularly maintaining tombs and remembering and honoring the dead. When Nebusemekh appears, he is greeted by Khonsemhab as a guest with a problem, not a ghost there to haunt, and the high priest shows him all hospitality in agreeing to help him with his situation. The story in its entirety would have been entertaining but would also have served the purpose of instilling an important cultural value in the listeners as it encouraged them to be mindful of and respect those who had passed on to the other side.

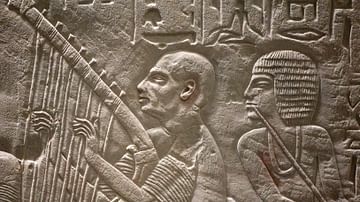

Respect for the dead, as noted, was an important cultural value to the Egyptians, no matter what the social status of the dead person was, but the author of the tale wants to make sure this point comes across and so makes Nebusemekh a lieutenant in the army under the great hero-king Mentuhotep II (c. 2061-2010 BCE) who united Egypt under Theban rule and initiated the period of the Middle Kingdom. Mentuhotep II is believed to be the king in the story because of his famous tomb at Deir el-Bahri, the necropolis featured in the story, and also his enduring fame.

Mentuhotep II's name is often substituted in translations (such as the one above) for the name Rahotep which appears in line III.6 when a translation is paginated, at the point where the ghost says, "When I was alive upon the earth, I was overseer of the treasury of King Rahotep". The ghost goes on to say, however, that he died in year 14 of the reign of Mentuhotep. This makes no sense as Rahotep (c. 1580-1576 BCE) was the first or second king of the 17th Dynasty while Mentuhotep reigned long before him as first king of the 11th Dynasty.

It is thought that the author may have confused the two kings since Rahotep, according to his stele at Coptos, was also associated with unifying the country under Thebes during the time of the Hyksos' occupation of Lower Egypt. It may also have been that at the time of composition Rahotep's name was associated with the earlier hero's as a kind of 'second Mentuhotep' and audiences of the time would have understood the allusion.

The actual name of the king is not as important as what that name would have signified to an audience: Nebusemekh was an important man closely associated with a great king and if his tomb could be allowed to fall into ruin so could anyone's. The details of the piece all go toward a single end of emphasizing the importance of respect for the dead and continual practice of the rites of remembrance.