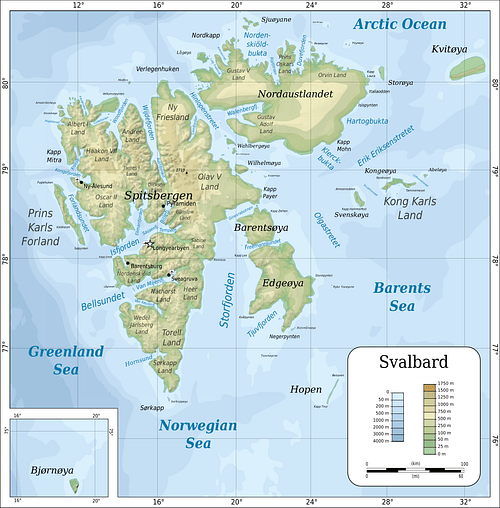

Svalbard is an archipelago in the Arctic Ocean on the northwest corner of the Barents Shelf. It is 800 kilometres (497 mi) north of mainland Norway and sits roughly midway between the top of Norway and the North Pole. It is bordered by Greenland (Denmark) in the west and Franz Josef Land (Russia) in the east. Svalbard (Old Norse for "Cold Coast") was formerly known by its Dutch name of Spitsbergen ("jagged mountains").

Svalbard consists of nine main islands, with Spitsbergen (formerly West Spitsbergen) being the largest with an area of 37,673 square kilometres (14, 545 square miles). The total area of the Svalbard archipelago is 62,700 square kilometres (24,208 square miles). Longyearbyen, the administrative centre of Svalbard, is the world's northernmost permanently inhabited settlement, named after John Munro Longyear (1850-1922), whose Arctic Coal Company started coal mining and surveying operations in Svalbard in 1906.

British mountaineer and explorer, Sir Martin Conway (1856-1937), who led an expedition to Svalbard in 1896, referred to the archipelago as 'no man’s land' or terra nullius because several nations had been mining, hunting, and exploring the area since the official discovery of Svalbard in 1596. The archipelago was international common land, unclaimed by any specific nation-state until Norwegian sovereignty was recognised by the Versailles peace negotiations at the end of World War I (1914-1918).

On 9 February 9 1920, the Spitsbergen Treaty was signed in Paris, and it came into force on 14 August 1925 when Svalbard came under Norwegian administration and legislation.

Despite this, the discovery of Svalbard and its early exploration have been debated. Due to a lack of historical sources and inconclusive evidence, several competing and controversial claims of discovery have been put forward, including that of Norway.

Four Discovery Theories

The Dutch discovery of Svalbard in 1596 is acknowledged as historical fact, but this is the western viewpoint and competes with an earlier Russian claim. There is also a Norse claim and a suggestion that Svalbard was settled during the Stone Age, around 3000 BCE. The four theories are:

Stone Age settlement.

In the 1970s, two Scandinavian archaeologists put forward the theory that Stone Age hunters may have formed a settlement on Spitsbergen. Flint objects were excavated at an 18th-century Russian whaling site at Russekeila. The archaeologists stated:

It has for a long time been clear to archaeologists that there should be possibilities for finds from the Stone Age on the Spitsbergen Islands. In NorthEast Greenland people have lived for long periods under much harder conditions; if man has not followed the reindeer to Franz Josefs Land and Svalbard it would be the only place in the world this has not happened. (quoted in Bjerck, 97)

Field surveys identified ten flint locations, dating to c. 4500-2500 years ago. Archaeologists have been divided over whether the artefacts were human-made or naturally flaked stone. An analysis of the lithic (stone) material in 1997 concluded they were not Stone Age artefacts.

A branded Nenet (Russian arctic) reindeer shot on Svalbard in 1911 led to the plausible explanation that the animal crossed the Barents Sea on drift ice, and Stone Age hunters may have followed a prehistoric reindeer's route.

The archaeological record is fragmentary at best, and the Stone Age settlement hypothesis has been largely dismissed. Yet, it is conceivable there may have been a prehistoric human presence on Svalbard, given climatic conditions were milder than they are today. The Inuit peoples inhabiting Greenland's Arctic and subarctic regions were the first explorers and cartographers of the Arctic and may have had knowledge of the upper Arctic islands.

The Norse claim or Viking theory

The name 'Svalbard' was mentioned in the 14th-century Islandske Annaler (Icelandic Annals) and recorded that Svalbard was discovered in 1194 by Norse sailors. In the Landnámabók (Book of Settlements, compiled in the early 12th century), there is a possible sailing instruction: "from Langanes on the north side of Iceland it is four doegrs sea to Svalbard on the north of Hafsbotn" (quoted in Rudmose Brown, 312).

The location of this 'Svalbard' is contentious. Hafsbotn was the ocean to the north of Norway and northeast of Greenland. Spitsbergen is only 1351 kilometres (840 mi) from Langanes, so it could refer to Spitsbergen's west coast, the island of Jan Mayen (a small volcanic island in the North Atlantic Ocean, 965 kilometres (600 mi) west of Norway) or even Greenland's east coast. In Old Icelandic, doegr can mean either a twelve- or 24-hour period. Using the twelve-hour definition pinpoints Jan Mayen as the most likely location of the Svalbard mentioned in the annals.

Norwegian historian Gustav Storm (1845-1903) was the first to suggest that the 'Svalbard found' recorded in the 1194 annals was evidence of early Norse visits to the archipelago. The suggestion gained popularity with the Norwegians, who were in the grip of nationalistic fervour, leading to the dissolution of the union between Norway and Sweden in 1905.

There was no exploration or surveying of the land said to be 'Svalbard,' and no further written sources, but the Norse were bold navigators, having discovered Greenland in 986 and Iceland in 870, so it is possible that Norwegian Vikings did indeed discover Svalbard.

The Russian or Pomor theory

By the late 1800s, an argument for the Russian discovery of Svalbard had emerged. In 1901, a Danish royal letter from 1576 was translated, suggesting that the Pomors had regularly sailed to Grumant, which is the Russian name for Spitsbergen. The Pomors – the indigenous population of Pomomerie (the Arkhangelskaya Oblast region in northeastern Russia that lies south of the White Sea) – were skilled sailors. They inhabited the coast of the White Sea and were already hunting on the nearby archipelago of Novaya Zemlya (also called Nova Zembla) in the early 16th century and possibly earlier.

It is known that Russian Pomors went to Spitsbergen between 1715 to 1850 to hunt polar bears, reindeers, foxes, walruses, and seals and wintered over in hunting stations. Russian archaeologists have discovered at least six sites on Spitsbergen, with one possibly dating to 1545. As with the Norse claim, archaeological evidence is inconclusive. Western historians have objected to the argument for Russian discovery because there is no mention of Pomors in whaling literature, nor are Pomor settlements marked on any maps before 1596.

The Barentsz theory

The Dutch discovery of Svalbard in 1596 by Willem Barentsz (1550-1597) is the commonly accepted historical narrative, although the controversial question remains: were there people on Svalbard before the Dutch reached it?

Willem Barentsz’s Discovery of Svalbard

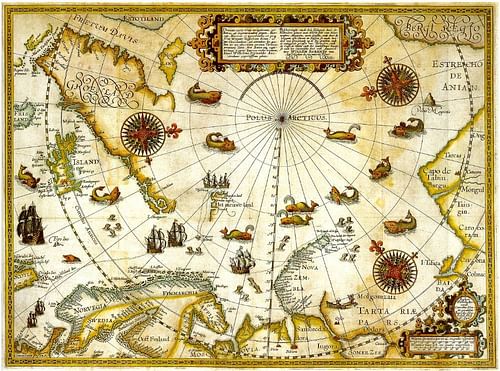

Willem Barentsz (c. 1550-1597) – anglicized as William Barents or Barentz – was a Dutch cartographer and navigator. He was born in Terschelling, an island in the northern Netherlands, and made three voyages in search of the coveted Northern Sea Route to Asia. The Dutch were already engaged in commercial activities in the Arctic and with northern Russia during the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly whaling and cod-fishing as well as exploration.

Between 1584 and 1668, there were attempts to find the Northeast Passage above Norway so that trading ships could reach Cathay (China) and the Spice Islands (the Moluccas) faster, and this search was part of Dutch global expansion plans. Their rivals, the British, had obtained a charter of incorporation for the Company of Merchant Adventurers of London in 1555. Generally known as the Muscovy Company, in 1556, they sent the early Arctic explorer and navigator Stephen Borough (1525-1584) in search of a Northeast Passage. He discovered the Kara Strait between Novaya Zemlya and Vaygach Island but found it full of ice and was forced to return to England.

Barents' first expedition in 1594, commissioned by a group of Amsterdam merchants, reached Novaya Zemlya, discovering the Orange Islands off the coast and mapping the archipelago before encountering icebergs and turning back. His second expedition in 1595, financed by the States General (Dutch parliamentary body), reached no farther than the Kara Sea and returned home after two crew members were attacked and killed by a polar bear.

The two expeditions were regarded as failures. Barents' third and final voyage was financed by the city of Amsterdam, and two ships under Barents' command set off in May 1596. Jacob van Heemskerk (also given as Heemskerck, 1567-1607) and Jan Cornelisz Rijp (d. 1613) captained the two ships, with Barents serving as pilot on De Witte Swaen (The White Swan). After discovering Bear Island (the southernmost island of the Svalbard archipelago), Spitsbergen was sighted on 17 June 1596. Barents is given historical credit for the discovery of Svalbard, and the Barents Sea along the northern coasts of Norway and Russia is named after him. The northwest corner of Spitsbergen was mapped, and the Dutch coat of arms erected before the two ships sailed again to Bear Island.

Barents and Rijp had a difference of opinion over the direction the ships should take, with Rijp wanting to explore Spitsbergen and Barents and Heemskerk wishing to cross the Barents Sea to Novaya Zemlya to map its northern coast. They parted ways, and Barents sailed to Novaya Zemlya with the intention of reaching the Vaygach Strait, but The White Swan became trapped in ice in August 1596, forcing Barents and his crew to overwinter there.

Gerrit de Veer (c. 1570 to c. 1598), who was an officer on Barents' second and third voyages, chronicled the expeditions and captured the moment the ship was crushed by ice:

Whereby all that was about and in it began to crack, so that it seemed to burst in a 100 peeces, which was most fearfull both to see and heare, and made all the haire of our heads to rise upright with feare. (quoted in Conway, 15).

The crew used lumber from the ship to build a hut to survive the gruelling conditions that were so cold the men slept with warmed cannonballs under their bedding. The shelter was named Het Behouden Huys ("safe home"), and Barents and his crew lived there until June 1597. They fought off polar bears and scurvy, which claimed many lives, including William Barents', who died on 20 June 1597.

Dutch attempts to discover the Northeast Passage ended with Barents' final voyage, and it was not successfully navigated until 1878-1879, when Finnish-Swedish explorer, Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld (1832-1901), sailed through it in the Vega.

Booming Whaling Industry

Curiously, Barents did not seem to note Svalbard's natural resources, such as oil and fur. It was not until May 1607 that English navigator Henry Hudson (d. 1611) on the Hopewell found whales, walruses, and seals in the waters around Spitsbergen. Hudson was not aware of Barents' discovery of Svalbard, but it is possible that he discovered Jan Mayen, calling it Hudson's Tutches (Touches). This gave rise to a claim to Spitsbergen in 1614 by the Muscovy Company on behalf of James I of England (r. 1603-1625). This claim was also based on the false assumption that the English explorer, Hugh Willoughby (d. 1554), who had attempted to find a northeastern route from Europe to the Far East, had discovered the Svalbard archipelago in 1553.

By 1612, the Dutch had started whaling activities in the Arctic, establishing the settlement of Smeerenburg in 1619. The Dutch Noordsche Compagnie, a whaling cartel, was established in 1614 and competed with the Muscovy Company, both companies sending whaling vessels to Spitsbergen. Europe needed oil for lamps and soaps, and baleen (whalebone) for corsets, umbrellas, and hoop skirts. The Dutch dominated the whaling industry with the help of experienced Basque harpooners, who boiled whale blubber in large copper pots at shore stations. There were more than 10,000 whalers in Spitsbergen and between 200-300 whaling ships by the late 17th century, including the French, Spanish, Hanseatic, and Danish. The Dutch alone had killed 1,255 whales, which yielded 41, 344 casks of blubber. By 1750, the feverish hunting of the Greenland right whale resulted in a diminished population and the abandonment of whaling stations, including Smeerenburg.

The Dutch had not demanded sovereignty over Svalbard following Barents' discovery, due to the Mare Liberum principle of 1609 – the Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo de Groot (1583-1645) had declared the high seas were open to all and paved the way for multiple nations' involvement in the Svalbard whaling industry. The Danish, however, also tried to claim Svalbard when Christian IV of Denmark (r. 1588-1648) argued that Spitsbergen was part of Greenland. The English referred to Spitsbergen as Greenland in an effort to deny the Dutch discovery and annexed Svalbard in 1614 for King James I – a claim ignored by the Dutch.

Trappers & Sealers

As the whalers abandoned Svalbard for new hunting grounds on the open seas, the next phase of Svalbard's history began with fur trappers and sealers arriving. In 1697, Russian vessels called lodyas with a crew of 24 men were seen in Spitsbergen waters and were sent by private companies such as the White Sea Fishing Company, private adventurers, and even monasteries. Pomor trappers came from Mezen, Archangel, Kola, Kem, Onega, and Rala on the White Sea and hunted polar bears, reindeers, foxes, seals, and walruses.

The first task of a Pomor hunting crew was to build its isbuschka or headquarters, and many of these stations, complete with Russian Orthodox crosses, have been excavated on Svalbard at Whales Point, Gotha Cove, and Cape Lee. The Pomors would overwinter, being replaced by a fresh hunting party the following year. During the long polar night (October-February), the Pomors faced the challenge of fighting off lethargy.

It will now be asked how the trappers employ themselves during the winter. Can you picture to yourselves pale, emaciated men, with dull, unillumined eyes, sitting in a damp barrack, lighted by an oil-lamp? Such are Archangel trappers in Spitsbergen during the long, dark night of winter. Like automata, each one ties a rope into an endless number of knots, and again unties it, and thus, now tying the knots, now undoing them again, spends nearly half the winter. At first sight, this pastime must seem strange, even ludicrous, but for the trappers it is a serious occupation. (quoted in Conway, 241).

The large Pomor settlement at Russekeila became known for its famous inhabitant, Ivan Starostin, who spent 39 winters on Svalbard, dying in 1826. Cape Starashchin is named after him.

In the 1790s, 2,200 Russian hunters in 270 ships were in Spitsbergen, but by the 1820s, intense hunting had led to diminishing walrus herds in particular, and Russian trading companies did not see a profitable return. The last mention of Pomor trappers in historical sources was in the winter hunting season of 1851-1852. The Pomors also found it difficult to compete with the Norwegians who reached the hunting grounds earlier – it was a 50-day voyage from the White Sea to Spitsbergen.

The Norwegians took over, overwintering for the first time in 1795-1796 and often occupying abandoned lodyas. They tended to hunt in the previously unknown eastern parts of Spitsbergen, and this led to some discoveries. Elling Carlsen (1819-1900), a well-known Norwegian seal hunter and explorer, circumnavigated the whole archipelago in 1861 and discovered Kong Karls Land, an island group in the archipelago. In 1898, Norwegian hunters came across a new island midway between Svalbard and Franz Josef Land, which they named Victoria Island.

The Arctic Coal Rush & the Industrialisation of Svalbard

Although polar bears were hunted until being protected on Svalbard in 1973, coal exploitation in the early 1900s was the next phase of Svalbard's history, particularly on the west coast. Coal had been discovered in Kings Bay by English sealer Jonas Poole (1566-1612) in 1610, but its economic potential was not fully realised until the Arctic Coal Company of Boston, Massachusetts, was established by American businessman John Munroe Longyear. He founded Long Year City (since 1926, Longyearbyen) in 1906, which accommodated miners working for the company (mostly Norwegian). By 1912, the Arctic Coal Company was extracting 40,000 tons.

No rules governed who could claim land, and between 1898 and 1920, over 100 land claims were made. The Swedes set themselves up in Svea and the Russians in Barentsburg and Pyramiden (closed in 1988 and now a preserved Soviet-era ghost town that can be visited). The two British mining companies were the Scottish Spitsbergen Syndicate and the Northern Exploration Company.

As the coal rush intensified, permanent settlements increased. The first school in Longyearbyen was built in 1920 by the Church of Norway and the Norwegian state-owned coal company, Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani, Svalbard radio started broadcasting in 1911, and a prefabricated hotel (Hotellneset) was erected as early as 1896 (later used by the Arctic Coal Company).

In January 1920, Spitsbergen's largest mining disaster in the American mine (known as Mine 1) killed 26 miners, and over the decades since, mining operations have closed due to safety and environmental concerns. Store Norske will close its last mine in the Svalbard archipelago in 2023.

The Global Seed Vault

Svalbard is best known today as a remote place in the high Arctic where Norwegian law requires residents to carry guns to protect themselves against polar bears and where no burials or cats are allowed (due to the permafrost and birdlife).

Svalbard's future may be to save humanity. The Global Seed Vault (also called the Doomsday Vault), situated deep inside a former Norwegian coal mine above Longyearbyen airport, was built in 2008 to secure millions of seed samples from the world's crop collections.