The popular view of life in ancient Egypt is often that it was a death-obsessed culture in which powerful pharaohs forced the people to labor at constructing pyramids and temples and, at an unspecified time, enslaved the Hebrews for this purpose.

In reality, ancient Egyptians loved life, no matter their social class, and the ancient Egyptian government used slave labor as every other ancient culture did without regard to any particular ethnicity. The ancient Egyptians did have a well-known contempt for non-Egyptians but this was simply because they believed they were living the best life possible in the best of all possible worlds.

Life in ancient Egypt was considered so perfect, in fact, that the Egyptian afterlife was imagined as an eternal continuation of life on earth. Slaves in Egypt were either criminals, those who could not pay their debts, or captives from foreign military campaigns. These people were considered to have forfeited their freedoms either by their individual choices or by military conquest and so were forced to endure a quality of existence far below that of free Egyptians.

The individuals who actually built the pyramids and other famous monuments of Egypt were Egyptians who were compensated for their labor and, in many cases, were masters of their art. These monuments were raised not in honor of death but of life and the belief that an individual life mattered enough to be remembered for eternity. Further, the Egyptian belief that one's life was an eternal journey and death only a transition inspired the people to try to make their lives worth living eternally. Far from a death-obsessed and dour culture, Egyptian daily life was focused on enjoying the time one had as much as possible and trying to make other's lives equally memorable.

Sports, games, reading, festivals, and time with one's friends and family were as much a part of Egyptian life as toil in farming the land or erecting monuments and temples. The world of the Egyptians was imbued with magic. Magic (heka) predated the gods and, in fact, was the underlying force which allowed the gods to perform their duties.

Magic was personified in the god Heka (also the god of medicine) who had participated in the creation and sustained it afterwards. The concept of ma'at (harmony and balance) was central to the Egyptian's understanding of life and the operation of the universe and it was heka which made ma'at possible. Through the observance of balance and harmony people were encouraged to live at peace with others and contribute to communal happiness. A line from the wisdom text of Ptahhotep (the vizier to the king Djedkare Isesi, 2414-2375 BCE), admonishes a reader:

Let your face shine during the time that you live.

It is the kindliness of a man that is remembered

During the years that follow.

Letting one's face "shine" meant being happy, having a good spirit, in the belief that this would make one's own heart light and lighten those of others. Although Egyptian society was highly stratified from a very early period (as early as the Predynastic Period in Egypt of c. 6000-3150 BCE), this does not mean that the royalty and upper classes enjoyed their lives at the expense of the peasantry.

The king and court are always the best-documented individuals because then, as now, people paid more attention to celebrities than their neighbors and the scribes who recorded the history of the time documented what was of greater interest. Still, reports from later Greek and Roman writers, as well as archaeological evidence and letters from different time periods, show that Egyptians of all social classes valued life and enjoyed themselves as often as they could, very like people in the modern day.

Population & Social Classes

The population of Egypt was strictly divided into social classes from the king at the top, his vizier, the members of his court, regional governors (eventually called 'nomarchs'), the generals of the military (after the period of the New Kingdom), government overseers of worksites (supervisors), and the peasantry. Social mobility was neither encouraged nor observed for most of Egypt's history as it was thought that the gods had decreed the most perfect social order which mirrored that of the gods.

The gods had given the people everything and had set the king over them as the one best-equipped to understand and implement their will. The king was the intermediary between the gods and the people from the Predynastic Period through the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) when the priests of the sun god Ra began to gain more power. Even after this, however, the king was still considered god's chosen emissary. Even the latter part of the New Kingdom (1570-1069 BCE) when the priests of Amun at Thebes held greater power than the king, the monarch was still respected as divinely ordained.

Upper class

The king of Egypt (not known as a 'pharaoh' until the New Kingdom period), as the gods' chosen man, "enjoyed great wealth and status and luxuries unimaginable to the majority of the population" (Wilkinson, 91). It was the king's responsibility to rule in keeping with ma'at, and as this was a serious charge, he was thought to deserve those luxuries in keeping with his status and the weight of his duties. Historian Don Nardo writes:

The kings enjoyed an existence largely free from want. They had power and prestige, servants to do the menial work, plenty of free time to pursue leisure pursuits, fine clothes, and numerous luxuries in their homes. (10)

The king is often depicted hunting and inscriptions regularly boast of the number of large and dangerous animals a particular monarch killed during his reign. Almost without exception, though, animals like lions and elephants were caught by royal game wardens and brought to preserves where the king then "hunted" the beasts while surrounded by guards who protected him. The king would hunt in the open, for the most part, only once the area had been cleared of dangerous animals.

Members of the court lived in similar comfort, although most of them had little responsibility. The nomarchs might also live well, but this depended on how wealthy their particular district was and how important to the king. The nomarch of a district including a site such as Abydos, for example, would expect to do quite well because of the large necropolis there dedicated to the god Osiris, which brought many pilgrims to the city including the king and courtiers. A nomarch of a region which had no such attraction would expect to live more modestly. The wealth of the region and the personal success of an individual nomarch would determine whether they lived in a small palace or a modest home. This same model applied generally to scribes.

Scribes & Physicians

Scribes were valued highly in ancient Egypt as they were considered specially chosen by the god Thoth, who inspired and presided over their craft. Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson notes how "the power of the written word to render permanent a desired state of affairs lay at the heart of Egyptian belief and practice" (204). It was the scribes' responsibility to record events so they would become permanent. The words of the scribes etched daily events in the record of eternity since it was thought that Thoth and his consort Seshat kept the scribes' words in the eternal libraries of the gods.

A scribe's work made him or her immortal not only because later generations would read what they wrote but because the gods themselves were aware of it. Seshat, patron goddess of libraries and librarians, carefully placed one's work on her shelves, just as librarians in her service did on earth. Most scribes were male, but there were female scribes who lived just as comfortably as their male counterparts. A popular piece of literature from the Old Kingdom, known as Duauf's Instructions, advocates a love for books and encourages young people to pursue higher learning and become scribes in order to live the best life possible.

All priests were scribes, but not all scribes became priests. The priests needed to be able to read and write to perform their duties, especially concerning mortuary rituals. As doctors needed to be literate to read medical texts, they began their training as scribes. Most diseases were thought to be inflicted by the gods as punishment for sin or to teach a lesson, and so doctors needed to be aware of which god (or evil spirit, or ghost, or other supernatural agent) might be responsible.

In order to perform their duties, they had to be able to read the religious literature of the time, which includes works on dentistry, surgery, the setting of broken bones, and the treatment of various illnesses. As there was no separation between one's religious and daily life, doctors were usually priests until later in Egypt's history when there is a secularization of the profession.

All of the priests of the goddess Serket were doctors and this practice continued even after the emergence of more secular physicians. As in the case of scribes, women could practice medicine, and female doctors were numerous. In the 4th century BCE, Agnodice of Athens famously traveled to Egypt to study medicine since women were held in higher regard and had more opportunity there than in Greece.

Military

The military prior to the Middle Kingdom was made up of regional militias conscripted by nomarchs for a certain purpose, usually defense, and then sent to the king. At the beginning of the 12th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom, Amenemhat I (c. 1991-c.1962 BCE) reformed the military to create the first standing army, thus decreasing the power and prestige of the nomarchs and putting the army directly under his control.

After this, the military was made up of upper-class leaders and lower-class rank and file members. There was the possibility of advancement in the military, which was not affected by one's social class. Prior to the New Kingdom, the Egyptian military was primarily concerned with defense, but pharaohs like Tuthmose III (1458-1425 BCE) and Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) led campaigns beyond Egypt's borders in expanding the empire. Egyptians generally avoided travel to other lands because they feared that, if they should die there, they would have greater difficulty reaching the afterlife. This belief was a definite concern of soldiers on foreign campaigns and provisions were made to return the bodies of the dead to Egypt for burial.

There is no evidence that women served in the military or, according to some accounts, would have wanted to. The Papyrus Lansing, to give only one example, describes life in the Egyptian army as unending misery leading to an early death. It should be noted, however, that scribes (especially the author of the Papyrus Lansing) consistently depicted their job as the best and most important, and it was the scribes who left behind most of the reports on military life.

Farmers & Laborers

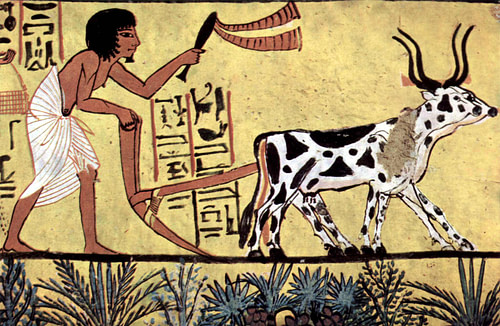

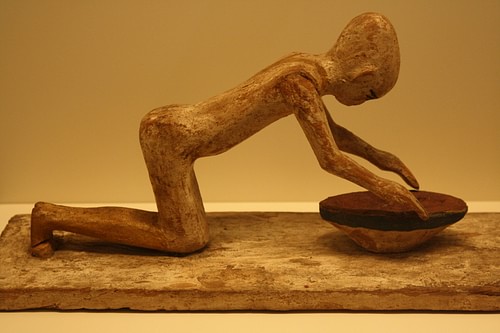

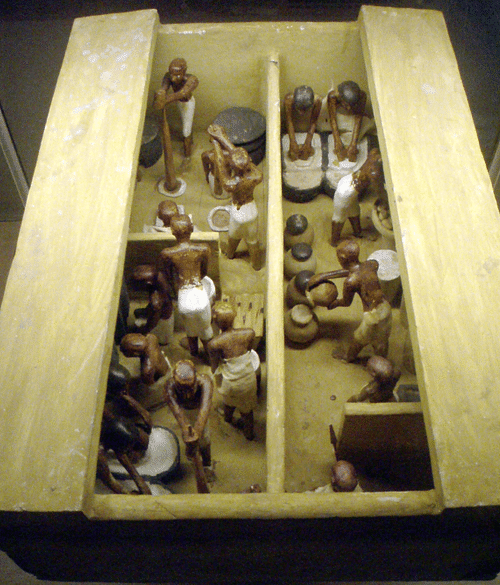

The lowest social class was made up of peasant farmers who did not own the land they worked or the homes they lived in. The land was owned by the king, members of the court, nomarchs, or priests. A common phrase of the peasants to start the day was "Let us work for the noble!" The peasants were almost all farmers, no matter what other trade they cultivated (ferryman, for example). They planted and harvested their crops, gave most of it to the land owner, and kept some for themselves. Most had private gardens, which women tended while the men went out to the fields.

Up until the time of the Persian invasion of 525 BCE, the Egyptian economy operated on the barter system and was based on agriculture. The monetary unit of ancient Egypt was the deben, which according to historian James C. Thompson, "functioned much as the dollar does in North America today to let customers know the price of things, except that there was no deben coin" (Egyptian Economy, 1). A deben was "approximately 90 grams of copper; very expensive items could also be priced in debens of silver or gold with proportionate changes in value" (ibid). Thompson continues:

Since seventy-five liters of wheat cost one deben and a pair of sandals also cost one deben, it made perfect sense to the Egyptians that a pair of sandals could be purchased with a bag of wheat as easily as with a chunk of copper. Even if the sandal maker had more than enough wheat, she would happily accept it in payment because it could easily be exchanged for something else. The most common items used to make purchases were wheat, barley, and cooking or lamp oil, but in theory almost anything would do. (1)

The lowest class of society produced the goods used in trade and therefore provided the means for the entire culture to thrive. These peasants also made up the labor force which built the pyramids and other monuments of Egypt. When the Nile River flooded its banks, farming became impossible and the men and women would go to work on the king's projects. This work was always compensated, and the claim that any of the great structures of Egypt were built by slave labor - especially the claim of the biblical Book of Exodus that these were Hebrew slaves oppressed by Egyptian tyrants - is not supported by any literary or physical evidence at any time in Egypt's history. The claim by certain authors such as Egyptologist David Rohl that one misses the evidence of a mass enslavement of Hebrews by looking at the wrong time period is untenable since no such evidence exists no matter what period of Egyptian history one examines.

Work on monuments like the pyramids and their mortuary complexes, temples, and obelisks provided the only opportunity for upward mobility of the peasantry. Especially skilled artists and engravers were in high demand in Egypt and were better paid than unskilled laborers who simply moved the stones for the buildings from one place to another. Peasant farmers could also improve their status by practicing a craft to provide the vases, bowls, plates, and other ceramics people needed. Skilled carpenters could make a good living creating tables, desks, chairs, beds, storage chests, and painters were required for decoration of upper-class homes, palaces, tombs, and monuments.

Brewers were also highly respected, and breweries were sometimes run by women. In early Egyptian history, in fact, they seem to have been entirely operated by females. Beer was the most popular drink in ancient Egypt and was frequently used as compensation (wine was never that popular except among royalty). Workers at the Giza plateau were given a beer ration three times a day. The beverage was thought to have been given to the people by the god Osiris, and breweries were presided over by the goddess Tenenet. Beer was taken very seriously by the Egyptians as the Greek pharaoh Cleopatra VII (69-30 BCE) learned when she imposed a beer tax; her popularity plummeted more for this one tax than for her wars with Rome.

The lower class could also find opportunity through work in metals, gems, and sculpting. The exquisite jewelry of ancient Egypt, gems mounted delicately in ornate settings, was created by members of the peasantry. These people, the majority of the Egyptian population, also filled the ranks of the army, and in rare cases, could become scribes. One's job and position in society, however, was usually handed down to one's son.

Homes & Furnishings

These artists were responsible for creating the furnishings for the lavish palaces, upper-class homes, and temples of Egypt as well as the tombs which were considered a person's eternal home. The king, his queen, and family lived in a palace which was richly decorated and had their needs tended to by servants. Scribes lived in or near the mortuary or temple complexes in special apartments and worked from scriptoriums while, as noted, nomarchs lived in greater or lesser accommodations according to their level of success. The peasants who provided the food for the upper classes also helped build their homes and supply them with chests, drawers, chairs, tables, and beds while they themselves could not afford any of these things. Nardo writes:

After a hard day's work, the farmers returned to their houses, which stood near the fields or in small rural villages located nearby. An average agricultural peasant's house featured walls made of mud bricks. The ceiling was fashioned from bundles of plant stems, and the floors consistend of hard-beaten earth covered by a layer of straw or mats made from reeds. There were one or two rooms (perhaps occasionally three) in which the farmer and his wife and children (if any) lived. In many cases, the stabled some or all of their farm animals in the same rooms. Because such modest homes lacked bathrooms, the residents had to use an outside latrine (a hole in the ground) to relieve themselves. Needless to say, water had to be hauled in buckets from the river or the nearest hand-dug well. (13)

By contrast, the palace of the pharaoh Amenhotep III (1386-1353 BCE), known as Malkata today, covered over 30,000 square meters (30 hectares) and included spacious apartments, conference rooms, audience chambers, a throne room and receiving hall, a festival hall, libraries, gardens, storerooms, kitchens, a harem, and a temple to the god Amun. The palace's outer walls were painted bright white while the interior colors were vibrant blues and yellows and greens.

The entire structure, of course, had to be furnished and these articles were supplied by the lower class workers. In its time the palace was known as 'the house of rejoicing' and other similar names. It is known as Malkata today from the Arabic for 'place where things are picked up' owing to the massive debris field found there from the ruined palace.

The apartments and homes of scribes, as with those of the nomarchs, were opulent or modest depending on their level of success and the region in which they lived. The author of the Papyrus Lansing, Nebmare Nakht, claimed to live in grand style and to own land and slaves on par with a great king. This claim is no doubt true, too, as it is well established that priests were able to achieve the same level of wealth and power as some rulers in Egypt, and scribes would have had that same opportunity.

Crime & Punishment

In ancient Egypt, as in every era of human history, the wealth of one person was often coveted by another who might choose to steal it, and in such cases, Egyptian law was swift. After the New Kingdom there was a police force, but even before this time, people were brought before the local official and charged with crimes ranging across the spectrum of criminal activity in the modern day. The state did not involve itself in local affairs unless the criminal had robbed or vandalized state property, such as robbing or defacing a tomb. Egyptologist Steven Snape writes:

The opportunities for criminal activity provided by the concentration of weatlth and property in towns and sities were seized upon wholeheartedly by some ancient Egyptians, just as they have been within all societies. Equally, significant centres of population and administration provided places where justice could be done and punishments meted out. However, the picture we get from ancient Egypt is that the administration of justice was pushed as far down to local level as possible. Villagers were expected to regulate their own affairs. (111)

Judgment and justice were ultimately the responsibility of the vizier, the king's right-hand man, who delegated that responsibility to officials beneath him, who further delegated to others. Even prior to the New Kingdom, there was an administrative building in any city called the Judgment Hall where cases were heard and verdicts rendered. In small towns and villages, these courts might be held in the market place. The local court was known as the kenbet, made up of community leaders of sound moral judgment, who would hear cases and decide on guilt or innocence.

In the New Kingdom, the judgment hall and the kenbet were gradually replaced by oracular judgments in which the god Amun would be consulted directly on a verdict. This was accomplished by a priest of Amun asking the statue of the god a question and then interpreting his answer through various means. Sometimes the statue would nod its head, and other times there would be different signs given. If the defendant were found guilty, then punishment was swift.

Most punishments were fines for minor offenses, but rape, robbery, assault, murder, or tomb robbing could result in mutilation (cutting off of the nose, ears, or hands), incarceration, forced labor (essentially slavery for life in many cases), or death. The Great Prison at Thebes held convicted felons who were used for manual labor on the Temple of Amun at Karnak and other projects.

There was no death row in Egyptian prisons since a person who was found guilty of a serious offense meriting the death penalty was executed immediately. There were no lawyers to argue a case and no appeals made after a verdict was rendered. The priests were entrusted by the people to give a fair and just hearing to any complaint and to judge according to the precepts of the gods, knowing that they faced a far worse fate in the afterlife should they fail in these duties.

Family & Leisure

Priests could be male or female. The chief priest of any religious cult was usually the same sex as the deity they served; the head of the Cult of Isis was female, that of the Cult of Amun, male. Priests could and did have families, and their children usually became priests after them.

This was the paradigm for all of Egypt as far as succession went: the children carried on the occupation of the parents, usually the father. Women had almost equal rights in ancient Egypt. They could own their own businesses, their own land, and their own homes, could initiate divorce, enter into contracts with men, have abortions, and dispose of their own property as they saw fit; this was a level of sexual equality which no other ancient civilization approached and which the modern era only initiated - under duress - in the mid-20th century CE.

At least four women ruled Egypt, the best known two being Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) and Cleopatra VII. This was not the norm, however, as most rulers were male. Royal women, for the most part, had slaves and servants who cared for the children and had no responsibility for cleaning or tending the home. They assisted their husbands in receiving foreign dignitaries and advancing certain policies. Women of the upper classes knew a similar lifestyle but might have taken more time caring for the children, while in the lower classes, the care of the home and children were wholly the woman's responsibility.

Marriages in ancient Egypt were more of a secular than religious affair. Most marriages, in any of the classes, were arranged by the parents. Girls were usually married around the age of 12 and boys around age 15. Royal children were often betrothed to those of foreign kings to seal treaties when they were little more than infants, though it was forbidden for women to leave Egypt as brides for foreign rulers since it was thought they would not be happy outside of their own land.

Since Egypt was the best of all places, it was considered disrespectful to a young woman to send her off to some lesser place. It was perfectly acceptable for foreign-born women to come to Egypt as brides, however. Once in Egypt, these women were accorded the same respect as natives. Women of all social classes were considered on par with their husbands, even though the man was considered the head of the household. Nardo notes:

Upper-class husbands and wives dined, held parties, and went hunting together, while both well-to-do and poorer women shared many legal rights with men. In fact, ancient Egyptian women seem to have enjoyed more freedom in their private lives than women in most other ancient societies, even if men made most of the really important decisions. Egyptian men benefitted from positive, loving relationships as much as their wives did. (23)

Although the wives of farmers did not go out to the fields with their husbands (for the most part), they still had plenty of work to do keeping the house clean, tending to any animals not used in plowing, administering to the needs of the elderly in the family, and raising the children. Women and children also would tend the family garden, which was an important resource for any family. Cleanliness was an important value of the Egyptians, and one's person and home needed to reflect that.

Women and men of all classes bathed frequently (priests more than any other profession) and shaved their heads to prevent lice and cut down on maintenance. When an occasion called for it, they wore wigs. Men and women also both wore makeup, especially kohl under the eyes, to help with the sun's glare and keep the skin soft. Tomb inscriptions and paintings also often show men and women plowing and harvesting in the fields together or building a home.

The life of the ancient Egyptians was hardly all work, however. They found plenty of time to enjoy themselves through sports, board games, and other activities. Ancient Egyptian sports included hockey, handball, archery, swimming, tug of war, gymnastics, rowing, and a sport known as 'water jousting,' which was a sea battle played in small boats on the Nile River in which a 'jouster' tried to knock the other out of his boat while a second team member maneuvered the craft.

Children were taught to swim at an early age, and swimming was among the most popular sports, which gave rise to other water games. The board game of Senet was extremely popular, representing one's journey through life to eternity. Music, dance, choreographed gymnastics, and wrestling were also popular, and among the upper classes, hunting large or small game was a favorite pastime.

There was also a sport called 'shooting the rapids,' which is described by the Roman playwright Seneca the Younger (1st century CE) who lived in Egypt:

The people embark on small boats, two to a boat, and one rows while the other bails out water. Then they are violently tossed about in the raging rapids. At length they reach the narrowest channels and, swept along by the whole force of the river, they control the rushing boat by hand and plunge head downward to the great terror of the onlookers. You would believe sorrowfully that by now they were drowned and overwhelmed by such a mass of water when, far from the place where they fell, they shoot out as from a catapult, still sailing, and the subsiding wave does not submerge them but carries them on to smooth waters. (cited in Nardo, 20)

After or even during such events, spectators enjoyed their favorite beverage: beer. The favored recipe most often consumed was Heqet (also given as Hecht), a honey-flavored beer similar to, but lighter than, the later mead of Europe. There were many kinds of beer (generally known as zytum), and it was frequently prescribed as a medicine as it made the heart lighter and improved one's spirits. Beer was brewed commercially and at home and was especially enjoyed at the many festivals the Egyptians celebrated.

Festivals, Food & Clothing

All of the Egyptian gods had birthdays which needed to be celebrated, and then there were individual birthdays, the anniversaries of great deeds of the king, observances of acts of the gods in human history, and also funerals, wakes, house-warming events, and births. All of these and more were celebrated with a party or a festival.

The festivals of ancient Egypt were each unique in character depending on the nature of the event, but all had in common drinking and feasting. The Egyptian diet was mainly vegetarian and consisted of grains (wheat) and vegetables. Meat was very expensive, and usually only royalty was able to afford it. Meat was also difficult to keep in the arid Egyptian climate, and so animals who were ritually slaughtered had to be used quickly.

Festivals were the perfect opportunity for indulging in every kind of excess, including meat eating for those who chose to do so, though self-indulgence was not appropriate at every gathering. Each celebration or commemoration had its own unique characteristics as historian Margaret Bunson explains:

The Beautiful Feast of the Valley, in honor of the god Amun, held in Thebes, was celebrated with a procession of the barks of the gods, with music and flowers. The Feast of Hathor, celebrated at Dendera, was a time of pleasure and intoxication, in keeping with the myths of the goddesses' cult. The feast of the goddess Isis at Busiris and the celebration honoring Bastet at Bubastis were also times of revelry and intoxication. (91)

These festivals were "normally religious in nature and held in conjunction with the lunar calendar in temples" but could also "commemorate certain specific events in the daily lives of the people" (Bunson, 90). At funerals, as one would expect, people dressed in respectful black (though the priests usually wore white) while at birthdays or other celebrations one wore whatever one pleased. At the Festival of Bastet, women wore nothing but a short kilt which they often raised in honor of the goddess.

Clothing in ancient Egypt was linen woven from cotton. In the Predynastic and Early Dynastic Periods, women and men both wore simple linen kilts. Children went naked from birth until around the age of ten. Bunson notes that "In time women wore an empire-type long skirt that hung just below their uncovered breasts. Men kept to the simple kilts. These could be dyed in exotic colors or designs although white was probably the color used in religious rituals or court events"(67). By the time of the New Kingdom women wore linen dresses which covered their breasts and went to their ankles while men wore the short kilt and sometimes a loose shirt.

Lower-class women, female slaves, and female servants are often shown wearing only a kilt through the New Kingdom period. At this same time, royal or noble women are shown wearing form-fitting dresses from the shoulder to the ankles and men are seen in sheer blouses and skirts. In the colder weather of the rainy season, cloaks and shawls were used.

Most people, of every social class, went barefoot in emulation of the gods who had no need for footwear. On special occasions, or when someone was going on a long journey or to a place where they might injure their feet or in colder weather, they wore sandals. The cheapest sandals were made of woven rushes while the most expensive were of leather or painted wood. Sandals do not seem to have a great deal of importance to the Egyptians until the Middle and New Kingdoms when they came to be seen as status symbols. A person who could afford good sandals was obviously doing well while the poorest people went barefoot. These sandals were often painted or decorated with images which could be quite elaborate.

At festival times - and there were many of them throughout the Egyptian year - the clothing of the priests was white, but people could wear anything they wanted or almost nothing at all. The Egyptians wanted to live life to its fullest, to experience all their time on earth had to give, and looked forward to its continuance after death.

One's earthly life was only a part of an eternal journey, and one's death was seen as a transition from one phase to the next. A proper burial was of the utmost importance to the ancient Egyptians of every class. The body of the deceased was washed, dressed in wrappings (mummified), and buried with those objects which they would want or need in the afterlife. The more money one had, of course, the more elaborate one's tomb and grave goods, but even the poorest people provided proper graves for their loved ones.

Without a proper burial one could not hope to move on to the Hall of Truth and pass the judgment of Osiris. Further, if a family did not honor the dead properly at death, they were almost guaranteeing the return of that person's spirit, which would haunt them and cause all manner of trouble. Honoring the dead meant not only paying respects to that individual but to the individual's contributions and achievements in life, all of which were made possible by the goodness of the gods.

Living with mindfulness of kindness, harmony, balance, and gratitude toward the gods, they hoped to find their hearts lighter than the feather of truth when they came to stand in judgment before Osiris after death. Once they had been justified, they would pass on to an eternity of the very daily life they had left behind when they died. Everything in their lives which seemed lost at death was returned in the afterlife. Their emphasis, in every aspect of their lives, was to create a life worth living for an eternity. No doubt many individuals often failed at this, but the ideal was one worth striving for and imbued the daily lives of the ancient Egyptians with a meaning and purpose which infused and inspired their impressive culture.