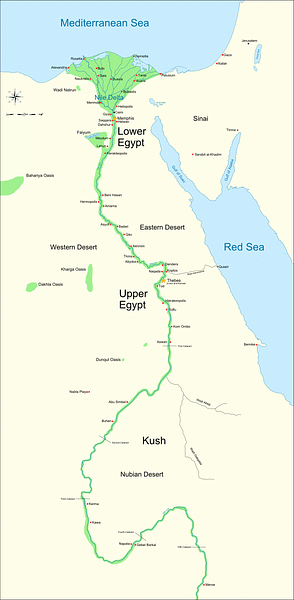

The Dodekaschoinos (literally "Twelve Cities" in Greek) was the name of a region in Lower Nubia that became an important province of the Ptolemaic Kingdom after it was annexed from Meroitic Nubia by the Egyptian kingdom. The area fell under Roman influence in the 1st century BCE following Egypt's conquest in 30 BCE. Its area extended between the 1st and 2nd Cataracts of the Nile in ancient Kush although parts are within modern-day Egypt.

History of the Region Under the Ptolemaic Kingdom

The beginning of Ptolemaic influence in Nubia began when Ptolemy II (283-246 BCE) led a campaign against the kingdom of Meroe c. 275 BCE and successfully conquered the province which was afterwards referred to as "the Twelve Cities". It then fell under the administration of the Egyptian nomes (a term for the provinces Egypt was divided into). It was at first technically a part of the Thebaid nome, but in reality, it was governed by the commander in charge of the soldiers garrisoned in the region. This situation remained unchanged until sometime in the 2nd century BCE when the region was reintegrated into the Elephantine nome with its civilian governor instead of being a part of the Thebaid nome.

The Dodekaschoinos retained much of its native administration, and a Nubian governor appears to have been appointed and had authority over the Nubian inhabitants of the province. Many Nubian inhabitants of the region integrated into Ptolemaic and later Roman society like their Egyptian counterparts, acquiring Greek language and education, citizenship rights and Greek or Roman names. Kushite or "Aethiopian" slaves are also known from throughout the Ptolemaic and Roman world, but particularly in Upper Egypt which was nearest to Nubia.

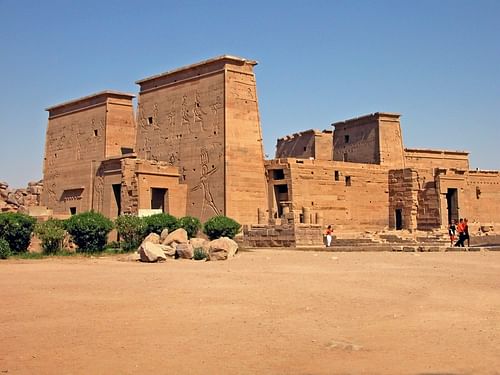

The Dodekaschoinos was part of the secession of Upper Egypt (205-185 BCE) that was supported by the Meroitic kingdom which sought to regain formerly Nubian territory through an alliance with the rebellious Egyptian factions. When Ptolemy V retook the province (c. 185-184 BCE), he dedicated the Dodekaschoinos and Philae to Isis as an attempt to legitimise the Ptolemaic rule of the region and ingratiate the Temple of Isis in Philae.

Trade & Cultural Significance

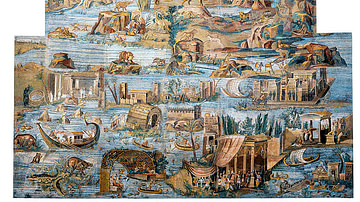

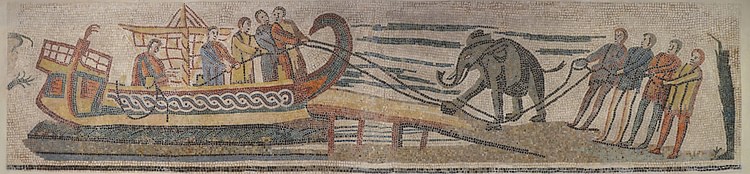

Its conquest by Ptolemaic Egypt opened up new trade routes to the Ptolemaic Kingdom from Nubia to the border cities of Ptolemais Theron and Elephantine. Elephantine, in particular, was at the centre of the trade in ivory, gold, iron, and slaves, which were transported further north by the caravan routes connecting the border trade cities to the Red Sea port cities and the rest of Egypt. African elephants were also imported for warfare, and this is mentioned in a dedication by Ptolemy III (246-222 BCE) who boasts of being the first to tame "Troglodytic" and "Aethiopian" elephants and use them for war in an inscription recorded by Cosmas Indicopleustes in his Christian Topography (c. 550 CE):

Great King Ptolemy, son of King Ptolemy [II] Queen Arsinoe, the Brother- and Sister Gods, the children of King Ptolemy [I] and Queen Berenice the Savior Gods, descendant on the paternal side of Heracles the son of Zeus, on the maternal of Dionysus the son of Zeus, having inherited from his father the kingdom of Egypt and Libya and Syria and Phoenicia and Cyprus and Lycia and Caria and the Cyclades islands, led a campaign into Asia with infantry and cavalry and fleet and Troglodytic and Aethiopian elephants, which he and his father were the first to hunt from these lands and, bringing them back into Egypt, to fit out for military service. (McCrindle, 58)

The use of African elephants in warfare by the Ptolemaic Dynasty came to an end after the battle of Raphia (217 BCE) against the Seleucid Empire made it clear that they were no match for the Asiatic elephants that were imported from the East, but the trade in ivory and exotic animals from the Nubian province remained lucrative, and elephants continued to be exported for various purposes.

It has been suggested that the conquest of Egypt by foreign powers in the mid-1st millennium BCE and the subsequent invasions of Lower Nubia upset pre-existing power structures and factored in the rise of the Meroitic dynasty in Nubia. The changes to existing power structures and Nubian relations with their neighbours to the north and south during this period were needed to secure its position as the dominant power south of Egypt that allowed Nubia to dominate the immensely lucrative trade from East Africa and the Red Sea silk route. This trade between more southern regions of Africa, Asia, and Egypt was integral to Meroe's importance as a hub of trade for the known world in spices, slaves, gold, iron, timber, animals, ivory, silks, and other items until Aksum superseded it as a trading power around the 4th century CE. These changes also brought new cultural influences to Nubia as it developed closer connections with the Mediterranean and Asia. Archaeological finds of Greek and Roman artefacts like jewellery and games testify to Meroe's wide trade network during this time which was closely intertwined with increasing Mediterranean trade from Northeast Africa as a whole.

During this time architectural influences from Ptolemaic Egypt also impacted Nubia. Temples like that at Musawwara et Sufra were erected in collaboration with Ptolemaic builders, displaying elements of Greek and Egyptian styles as well as traditional Kushite designs. The "Royal Baths", a water sanctuary in Meroe dating to the 3rd century BCE, bear elements of Hellenistic and Roman architecture comparable in some respects to Alexandria or Cyrene. Depictions of Hellenised Nubian deities and Greek deities like Pan have been found at the site.

Relationship with Philae

Philae had been a religious and political hub of the region since the Late Period of Ancient Egypt when Nectanebo I (379-361 BCE) constructed a temple to Hathor which continued to be renovated under later pharaohs. The fate of this city was often intertwined with that of Lower Nubia and Upper Egypt's fluctuating border as a result of its location, and it was often used as a nexus point between Lower Nubia and Upper Egypt and a meeting place for the rulers of Egypt and Nubia. It was the symbolic line of demarcation between Egypt and the Dodekaschoinos in the Ptolemaic and Roman periods.

A network of commerce existed between Nubia and the Ptolemaic kingdom through Philae and the Dodekaschoinos. The regional temples oversaw trade and donations as well as fostering cultic connections throughout Egypt and Kush. The Ptolemaic kings erected temples to Thoth and to Nubian gods like Arensnuphis and Mandulis in the Dodekaschoinos, and during some festivals, Nubian gods (i.e. the statues and their attending priests) made pilgrimages from the Nubian temples to Philae in processions down the Nile. Ptolemaic rulers from Ptolemy II all the way down to Cleopatra VII (51-30 BCE) patronised this site. Various dedications record occasions where Ptolemids visited Philae for religious purposes. Some Nubians held priestly offices at Philae and represented the Meroitic king in diplomatic capacities at the Temple to Isis at Philae. Nubian envoys to Philae are mentioned in various Ptolemaic and Roman contexts bearing gifts, tribute, and diplomatic messages.

The Dodekaschoinos After the Roman Conquest of Egypt

After the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BCE, the region faced further conflicts and changes as Augustus (27 BCE -14 CE) recognised both the potential dangers that Nubia held to his rule and the opportunities that its conquest could bring. The first prefect of Roman Egypt, Cornelius Gallus, faced rebellions in Upper Egypt and Lower Nubia as a result of taxation c. 29 BCE, but he was able to quickly quell these rebellions and attempted to assert Roman authority over Nubia according to a stela erected at Philae which reads:

Praefectus Aegypti Cornelius Gallus says to pride oneself on his victory he achieved: "Gaius Cornelius Gallus son of Gnaeus, the Roman cavalryman, first prefect of Alexandria and Egypt after the defeat of kings by [Augustus] Caesar son of the divine, and the vanquisher of Thebaid's revolution in fifteen days, defeated the enemies twice during it in a general battle, and took over five cites by force: Boreses, Coptos, Ceramici, Diospolis Megaly, and Ophion, and having captured the leaders of these revolutions. Having led his army beyond the cataract of the Nile, where neither the armies of the Romans nor those of the kings of Egypt had gone before, and subjugated Thebaid, the source of dread for all kings, and given listening to the ambassadors of the king of Aethiopia and taken that king into protection, and appointed a ruler for the Tiracontoschoenus [Dodekaschoinos]. . .in (?) Aethiopia, he [Gallus] presented this dedication and gave thanks to the ancestral gods and the Nile, his helper." (Translation from M. Solieman)

These actions and the hubristic boasts made concerning his achievements led to Augustus stripping him of command and replacing him with Gaius Petronius who was evidently more successful concerning the conflict with Nubia and less over-reaching in his ambitions in his first prefecture. Augustus replaced him with Aelius Gallus in 26 BCE, but when Gallus went east to lead Augustus' planned conquest of Arabia (c. 25 BCE) Queen Amanirenas of Meroe took the opportunity to invade the Dodekaschoinos and then Upper Egypt. They successfully occupied Syene, Philae, and Elephantine, where they expelled the Jews, and in the process of their raids and occupations, they carried off Roman prisoners and several bronze statues of Augustus. One of these statues, known today as the "Meroe Head", was found in 1910 CE where it was buried, beneath a Meroitic temple to the Nubian god Arensnuphis, a patron of warfare among other things.

In 24 BCE Petronius was restored to the position of prefect of Egypt, and in 23 BCE he led a punitive expedition south into Meroe allegedly as far south as the city of Napata, which he sacked. After recovering prisoners and statues as well as taking hundreds of Nubian captives he retreated north, establishing the new border of Roman territory at Primis (Qasr Ibrim). Queen Amanirenas retaliated with vigour and made attempts to retake Primis in 22 BCE which Petronius stalled. Afterwards, the Meroitic kingdom made overtures to Petronius in hopes of a negotiation, but Petronius chose to refer these to Augustus. Around 22-21 BCE Augustus agreed to all the terms set by Amanirenas' envoys while Meroe returned many (but evidently not all) of the stolen statues and ceased hostilities. The agreed-upon border restored the shape of Roman Nubia to roughly that of the Ptolemaic province, with the restored border falling on the southern edge of the Dodekaschoinos.

In the Roman Imperial period, the trade routes and political connection between Nubia and the Dodekaschoinos strengthened, and Nubians continued to have a strong religious and diplomatic presence as far north as Philae. A large proportion of the Sub-Saharans generally referred to as “Aethiops” who inhabited Egypt and the rest of the Roman Empire as citizens, subjects, or slaves originated in and emigrated or were exported from Nubia. The importance of the temple networks continued until Philae's conversion to Christianity in the 4th century CE when Christianity became the dominant religion in Egypt and Nubia and many temples were abandoned, destroyed, or converted into chapels.