Donato Bramante (c. 1444-1514 CE) was an Italian Renaissance architect whose most famous project was the design for a new Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome, even if this work remained unfinished at his death. Bramante had also designed the influential Tempietto of San Pietro, a classical-inspired circular temple in Rome, and parts of the Sant'Ambrogio Basilica and monastery complex of Milan. The architect's Palazzo Caprini in Rome, with its lower storey of arched shop fronts and classical columns above, was hugely influential on palace buildings thereafter. For these works, Bramante is justifiably considered the founding father of High Renaissance architecture and a master of reimagining elements from classical antiquity to create simple yet elegant buildings built on a grand scale.

Early Life

Donato Bramante was born Donato di Pascuccio near Urbino, Italy, around 1444 CE. His parents were farmers, and his father, aiming to obtain a better life for his son, sent him off to study painting. Bramante may have been a student in the workshop of the artist Piero della Francesca (c. 1420-1492 CE) in Urbino. Early on, Bramante was interested in the perspective effects employed by Andrea Mantegna (c. 1431-1506 CE) in his paintings and frescoes. Interestingly for Bramante's future career, these illusionary techniques very often involved elements of architecture. In 1477 CE, Bramante moved to Bergamo where he is known to have painted murals, some with trompe-l'oeil effects. Unfortunately, only fragments remain of these works. Next to no other biographical details survive of what the young artist did up to his mid-thirties, and no complete paintings or sketches can be securely attributed to him, even if it seems he never gave up painting entirely.

The Milan Years

Bramante lived and worked in Milan from 1480 CE. There he spent time at the court of Ludovico Sforza, who reigned as regent and then Duke of Milan (1480-94 & 1494-99 CE respectively). His move into architecture first appears in the historical record in 1485 CE and was perhaps influenced by contact with Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519 CE), who had moved to Ludovico's court in 1482 CE. Leonardo and Bramante corresponded, and the former would have introduced the latter to the work of the great Florentine architect Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446 CE), who famously designed the great Dome of Florence's cathedral and whose views on perspective and reconsideration of architectural and urban spaces were influential throughout the Renaissance. Brunelleschi promoted classical proportions, simple geometry, and harmony in a new architectural language which challenged the hitherto dominance of medieval architecture. Another influence on Bramante was the work of the architect Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472 CE), also an advocate of boldly reusing features of classical architecture.

Bramante's first known architectural project was the Church of Santa Maria Presso San Satiro, notable for its illusionistic choir making the church interior seem much larger than it really is. The east exterior provides another illusion of perspective and so the church as a whole is already an indicator of how Bramante used his training as a painter and so differed from his predecessors, as the historian P. Murray here notes:

This feeling for architectural space as a series of planes and voids, like those in a painting, rather than a series of three-dimensional solids, like in architecture, distinguishes Bramante from Brunelleschi and from most of the Florentine architects of his own generation. (113)

Between 1492 and 1497 CE, he worked on Milan's Santa Maria delle Grazie church, famous today for its refectory which houses the Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci. Bramante likely designed and built the church's new apse, transept, crossing, and dome.

A contemporary project was the new canonica (clergy residence) and cloister for the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio (Saint Ambrose), Milan's patron saint. Some of the columns have small bumps, and these represent cut-off boughs in recognition that early columns in antiquity were made from tree trunks. Bramante designed two more cloisters for the adjacent monastery, which is today an elegant part of the Catholic University of Milan.

The architect was also given a brief by Ludovico Sforza in 1493 CE to assess the fortifications along Lombardy's border with Switzerland. Another task for Ludovico was the design and organisation of public spectacles. Bramante continued to move around the Lombardy region, likely designing the massive rectangular piazza in Vigevano between 1492 and 1494 CE. Always busy with his chief patron's many projects, we know that in his free time the architect wrote sonnets and was a keen amateur musician. Bramante's poetry reveals a keen sense of humour and a man who did not take himself or life too seriously.

Move to Rome

In 1499 CE Bramante relocated to Rome. Probably, he was persuaded to leave Milan by the imminent French invasion towards the end of that year. Rome, with its wealthy patrons and abundance of ancient buildings, was an attractive option for an architect with experience and an interest in antiquity. He soon gained employment, and in 1500 CE, Bramante designed the cloister for the Santa Maria della Pace church.

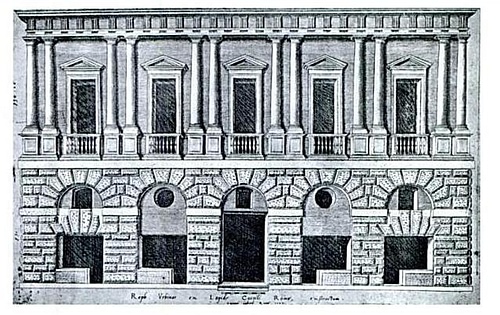

In 1501 CE he designed the Palazzo Caprini, also known as the 'House of Raphael' after the artist Raphael (1483-1520 CE) began living there from 1517 CE. The building is now unrecognisable after a late-16th century CE restoration. However, Bramante's version, with its upper floor of classical orders and lower rusticated floor of arched shop fronts combining to create a strictly symmetrical facade, was hugely influential on palace buildings in Italy for the next two centuries. There is another connection between Bramante and Raphael, at least according to the art historian Giorgio Vasari in his The Lives of the Most Excellent Italian Architects, Painters, and Sculptors (1550 CE, revised 1568 CE). Vasari states that Bramante designed the architectural elements for Raphael's School of Athens fresco in the Vatican (c. 1511 CE), and as a show of thanks, the artist painted Bramante in the scene as the Greek mathematician Euclid (active 300 BCE). Bramante can be seen as himself in the fresco on the opposite wall, the Disputa, also by Raphael. Bramante appears in the left foreground showing a book to the painter Fra Angelico (c. 1395-1455 CE).

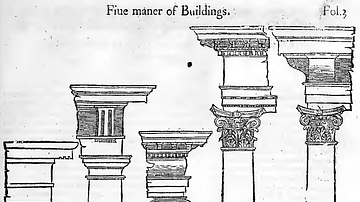

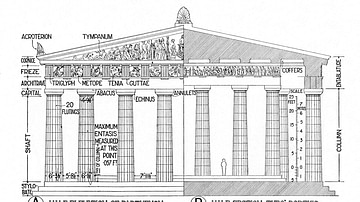

Working for Pope Alexander VI (r. 1492-1503 CE), Bramante was likely the designer of several monumental fountains, notably in Piazza Santa Maria and Saint Peter's square. In 1502 CE Bramante was commissioned to design and build the circular Tempietto of San Pietro in Montorio, again in Rome. The building, located on what was considered the site of Saint Peter's crucifixion, was completed c. 1510 CE and was the first Renaissance structure to use the complete Doric order from antiquity. The design is an excellent example of Renaissance humanism thinking expressed in architecture. The 16 classical columns (fittingly, all were recovered from ancient buildings) are not only elegant and undecorated but the circle design of the temple was considered the perfect shape for a church as that was thought to be the noblest of geometrical forms. In addition, Christian buildings that commemorated martyrs were traditionally centrally-planned structures. Thus, the Tempietto is an excellent example of the blending of classical and Christian ideas.

A new pope was elected in 1503 CE, Pope Julius II (r. 1503-1513 CE), and he turned out to be one of the greatest patrons of art during the Renaissance and a man on a mission to improve Rome's fortunes in all things. Julius' interest in Bramante began in 1504 CE when he was employed to remodel the Vatican Palace and the Villa Belvedere, which had, over the centuries, become something of a sprawling mess of buildings. Bramante's solution was to create a central court enclosed by two galleries or covered loggias, which used Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian columns. A number of courtyards connected by ramps and stairs ascended from the Vatican Palace to the Belvedere. A problem with some of the courtyard foundations delayed the completion of the project until after Bramante's death, and the palace part of the project never got underway at all. Very little of Bramante's designs can be seen at the site today following extensive rebuilding over the years.

Another of Rome's buildings Bramante is associated with (although not with absolute certainty) is the Cancelleria Palace, completed c. 1511 CE. Bramante made several new streets across the city, too. The sheer quantity of new building work in this period required innovations in materials that were cheap and quick to install. This led to Bramante pioneering the use of cast vaults and stucco.

Saint Peter's Basilica

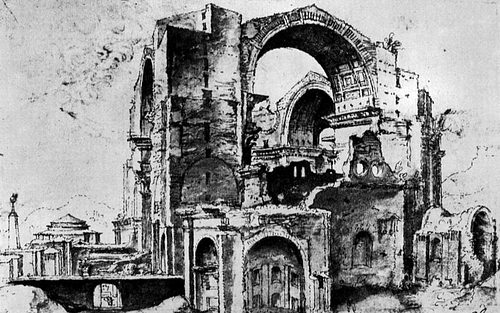

Julius II had an even more prestigious project for Bramante: to build a massive new church, St. Peter's Basilica. This seemingly never-ending project began in 1506 CE when the first foundation stone was laid on 18 April. The project was one of the most ambitious ever undertaken, and it eventually came to involve just about every Renaissance architect of note. Bramante was made the superintendent of the Pope's architectural plans. First, the area was cleared, which necessitated the removal of the badly decayed Basilica of Constantine. Indeed, so many old buildings were swept away for his reshaping of the Vatican that the architect gained the unfortunate nickname of 'Ruinante'. Bramante's lasting contribution to what would become Saint Peter's Basilica was the four giant piers and their arches. As it turned out, his original designs were changed, but the central cross of what Bramante had envisaged as a Greek cross plan, remained. Indeed, the centralised plan of the church would be much copied across Italy.

While Bramante was busy building in the Vatican, Michelangelo (1475-1564 CE) was nearby decorating the Sistine Chapel ceiling (1508-1512 CE). Michelangelo would himself be involved in the basilica project after Bramante's death. The artist laments in the following letter the changes subsequent architects had made to Bramante's original plans:

One cannot deny that Bramante was as skilled in architecture as anyone since the time of the ancients. He it is who laid down the first plan of St Peter's, not full of confusion, but clear, simple, luminous and detached in such a way that it in no wise impinged upon the Palace. It was held to be a beautiful design, and manifestly still is.

(Anderson, 77)

Death & Legacy

When Pope Julius II died in 1513 CE, Bramante was kept on by his successor Pope Leo X (r. 1513-1521 CE), but by then his own health was failing. The architect may have submitted a plan to Leo X for better controlling Rome's water system which would avoid the regular floods caused by the River Tiber. Bramante died in Rome on 11 April 1514 CE. Appropriately enough, he was buried in St. Peter's.

Unfortunately, Bramante's writings, which we know covered many subjects relevant to architecture such as studies in perspective, fortifications, and Gothic architecture, have not survived. His influence, though, lived on through his buildings, which were copied by other architects for centuries. The circular Tempietto on Montorio is just one example. With its elegant facade and barrelled centre rising straight through a ring of columns to a soaring dome, it was imitated everywhere thereafter and can still be seen today in buildings worldwide, from London's Saint Paul's Cathedral to the United States Capitol.