Edouard Manet (1832-1883) was a French modernist painter whose work is celebrated for its candid realism. Works like Olympia, an entirely modern nude, broke the artistic convention that great art should not concern itself with contemporary life. By capturing Parisian café society, Manet inspired later artists to break entirely free from any artistic convention they wished.

Early Life

Born in Paris on 23 January 1832, Manet's family was a wealthy one of lawyers, civil servants, and landowners. Manet's father, Auguste, was a high court judge while his mother, Eugénie Désirée Fournier, also had high connections. Both parents enjoyed an independent income from wealth inherited from their own parents. Edouard's uncle, Edmond Fournier, encouraged an interest in art in the young boy for whom he made sketches and took to Parisian galleries. Manet went through his school years without any apparent distinction despite being enrolled in the prestigious Collège Rollin in Paris. There he started a life-long friendship with the journalist Antonin Proust (1832-1905).

An attempt to join the French Navy met stormy waters when he failed the entrance exams in 1848. Undeterred, Manet joined as a cadet and promptly found himself in Rio de Janeiro in time to catch its famous Carnival. Manet used the long sea voyage well, sketching the sea and his fellow mariners.

Artistic Influences

Back in France again, Manet persuaded his father that he could pursue a career as an artist, and he enrolled in the school of Thomas Couture (1815-1879) in 1850. His father was reluctant, having wanted Edouard to study law, but he supported his son through his career, which meant Manet was not obliged to live off his art. Manet was an admirer of past masters like Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) and the use of dark backgrounds, flat figures, and sharp opposites of light and shade. In 1853, Manet visited Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium to see the great artworks there. He was also impressed with the freedom Dutch and Italian contemporary artists had to paint everyday life. In the 1850s in Europe, Japanese prints became popular and their 'flatness', and unexpected cutting of scenes would inspire Manet and others.

Another influence was the Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) who used brushstrokes as an effect instead of the hitherto preoccupation with making them invisible. Then there was the tantalising work of the realist Gustave Courbet (1818-1877), who chose everyday peasant life as his subject and who daringly applied paint using a palette knife. Manet was tiring of the traditional methods young artists were encouraged to use to improve their craft such as endlessly sketching plaster casts of body parts or ancient statues. Manet was inspired by artists like Delacroix and Courbet, who had shown that a career outside the Salon system was possible (even if Delacroix did become a Salon judge himself). Manet wanted to paint life as it happened outside the studio. Setting up his own studio in February 1856, he took things slowly, copying paintings to find his way artistically through experimentation. His first complete and truly original work, which captures his search for the ordinary, was The Absinthe Drinker of 1859, a massive canvas 6 ft (1.8 m) high. A new force in art had appeared.

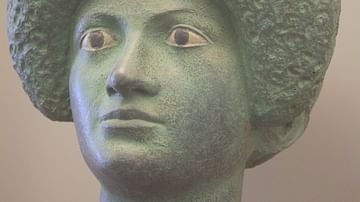

Appearance & Family

Manet was a handsome man with a red-blonde beard but prematurely receding hair. The very opposite of the archetypal Bohemian artist, he had a penchant for fine clothes; he frequently sported a top hat and cane and strolled at leisure through Parisian café society, the ultimate flâneur. He had great manners, charm, and optimism, and he made friends easily.

In 1849, Manet met the Dutch girl Suzanne Leenhoff, they married in October 1863. Suzanne had been employed by Manet's father to teach Edouard piano. The pair were lovers long before they married and (probably) had a child together, Léon-Edouard, born in January 1852. The scandal this would have caused if made public meant Léon-Edouard was treated as Suzanne's younger brother, and Manet never formally acknowledged his son (except indirectly in his will). Both Suzanne and Léon-Edouard appear in many of Manet's paintings of calm domestic life. Another close associate was the impressionist painter Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) who eventually married Manet's brother. A fourth important woman in Manet's life was his most noted pupil, Eva Gonzalés (1849-1883) who died young, aged 33.

Challenging Conventions

Manet's style was shocking to the Establishment. He left seemingly wild brush strokes visible and avoided the careful build-up of texture using gradual transitions of colour expected of fine artists. Manet also shocked by not painting traditional subjects: historical and mythological scenes or landscapes that were picturesque. Manet's choice of everyday Parisian life, especially its café culture, portraits of ordinary folk, and imaginative still life works were all at odds with the ultra-conservative art world and the Paris Salon where such works were exhibited and sold.

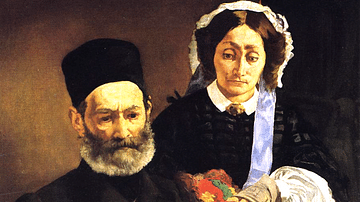

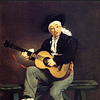

Manet made further provocations with exactly how he imagined the world. His Absinthe Drinker was a seemingly homeless man; unsurprisingly, it was rejected by the Salon in 1859. The uproar caused Manet to briefly return to a more classical approach. Manet's portrait of his parents, Monsieur et Madame Manet, and The Spanish Singer, both much more conservative works, were accepted by the Salon in 1861, the latter even gaining a commendation. Meanwhile, his Fishing, which shows Manet and Suzanne, was exhibited in St. Petersburg (but not bought).

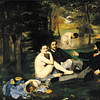

Manet's 1863 painting Lunch on the Grass (Déjeuner sur l’herbe) was a powerful return to his radical approach. Picnics were an everyday activity, but Manet made his shocking by having the two men in the scene clothed in contemporary attire, one woman half-dressed, and the second naked (who, staring at the viewer, seems unashamedly so). If this scene had been painted in the traditional way, as a timeless allegory or mythological subject, it would have been accepted when it was displayed in the Salon des Refusés. As it was, Manet's contemporary realism made the whole thing obscene for many critics, who also took exception to his obvious brushwork and gaudy colours. Emperor Napoleon III (r. 1852-1870) was in no doubt as to the painting's irreverence, describing it bluntly as "an offence against modesty" (Rodgers, 9). The painting's clear nod to several masterpieces of Renaissance art was lost in the furore.

Edouard Manet: A Gallery of 30 Paintings

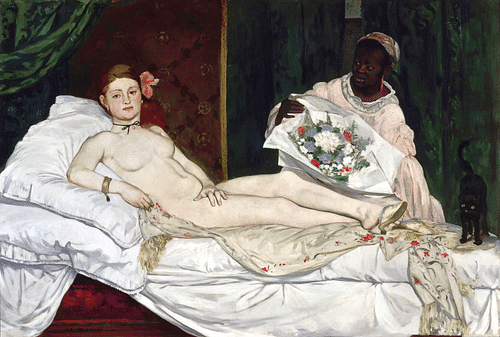

More scandal followed. Manet's painting in the 1865 Salon exhibition was just as shocking as his picnic two years before. It is surprising Olympia was accepted, but the Salon would soon regret its decision. The central nude figure was Manet's long-time model Victorine Meurent, shown reclining on her bed and confidently gazing directly at the viewer. Once again, Manet's nude was shockingly modern and unconventional. One critic stormed that Manet was a "brute who paints green women with dish brushes" (Rodgers, 115). The critics, focussing on the nude courtesan and her confident stare, missed the other innovations Manet was presenting: the unusual colours, the way the two figures seem to move towards the viewer, and the flatness of the composition. Faced with the uproar, the Salon rehung the painting higher up on the wall, hoping it would be less likely to prick the sensitivity of the bourgeoise public strolling through the gallery.

After his father's death in 1862, Manet inherited an independent income, and so he now only needed to seek the favour of critics for his own satisfaction and ambition. He could also take heart from the shrewd assessment of the Belgian artist Alfred Stevens (1823-1906): "Mediocrities do not cause such a clamour" (Rodgers, 29). Encouraged by fellow artists and friends like the poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) and Émile Zola (1840-1902), Manet focussed now on everyday modern Parisian life and painting his way, capturing the people who frequented cafés, brasseries, and café concerts. However, Manet, like many of his contemporaries, still strove for 'official' recognition and continued to regularly submit to the Salon. Rejections abounded, and after two of his paintings were returned with the hideous red 'R' in 1876, Manet decided to show off his work in his own studio. When the World Fair was held in Paris in 1867, Manet set up his own pavilion on Place d'Alma and showed 53 of his works. Manet did not sell a single painting in his one-man show, but the lack of customers at least gave him time to paint a memorable panorama of the fair as seen across the way from his booth.

The Manet Style

While Manet's travels to Spain in 1865 resulted in paintings of aspects of Spanish culture such as bullfights, Paris was his first love, and one of the finest examples is Music in the Tuileries Gardens. Painted in 1862, it has often been called the first modern painting. Fashionable, real-life figures like the composer Jacques Offenbach are captured in a bustling outdoor scene, a contemporary activity captured in a contemporary manner. There was still a nod to the Old Masters in the epic scope of the scene, but here was modern art indeed. The critics were outraged as usual.

Manet's scenes often show figures in solitude, even if they are surrounded by crowds such as on a café terrace, an effect achieved by never having the subjects look at each other. The viewer is often left wondering what the relationship is between these disconnected figures. Beautiful women were a favourite subject, notably Victorine Meurent and Berthe Morisot, who Manet painted eleven times.

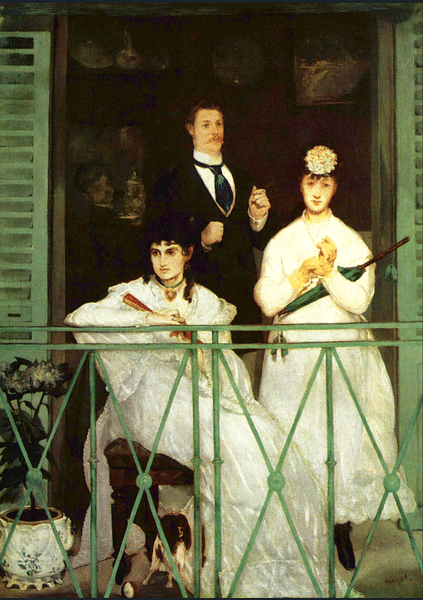

Manet also liked intimate scenes with a very tight focus and presented with more theatre than realism. An example of this is his 1868-9 painting, The Balcony. Here, three figures stand on a balcony with their relationship left a mystery. Manet expertly uses colour, contrasting the dark interior behind the figures with white clothing and the turquoise of the shutters and railings. A second example of the artist's skill in unusual scenes is the Lunch in the Studio, also of 1868. The central figure is probably Léon-Edouard, and he seems to deliberately hide the lunch on the table behind him. Once again, the relationship between the three figures in the scene is left unclear, and, like many of Manet's works, they seem to crowd towards the viewer, who is, nevertheless, left an idle spectator, since none of the three is looking at anything in particular. Critics were baffled by both of these paintings, but they were selected for the 1869 Salon.

Manet sometimes used pastels on canvas, particularly for intimate portraits. He made sketches and etchings, which he worked from to produce oil on canvas versions. In oils, Manet used the alla prima technique (aka 'wet on wet') which was to paint directly on an unprepared canvas, allowing him to scrape off the day's work if he was dissatisfied. Manet used black very often, especially for clothing and framing a face in portraits, and he liked to emphasise contrasts of colour.

Manet was one of the least 'impressionistic' of the modern artists often grouped by that name. He strived to capture the realism of daily life and was less interested in capturing momentary episodes of light, something which characterised the impressionists. With this approach, he captured not only life in Paris but still life subjects, portraits, cats (especially lithographs), horse races, and seascapes, usually at Boulogne, where he often visited for a holiday.

The Batignolles

Through the 1860s, Manet became the recognised leader of modern Parisian artists – he was older and richer than most of the others. They hung about cafés, passionately discussing what should be the new direction of art, especially the Café Guerbois and others in the Batignolles area of Paris. This group, which included such future household names as Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Manet's good friend Edgar Degas (1834-1917), and Claude Monet (1840-1926), became known as 'the Batignolles'. There were also literary men in the group like Émile Zola. There were often heated discussions in the group. Manet once got into an argument with the critic Louis-Edmond Duranty that boiled over into a duel in 1870. Manet wounded his opponent, but the pair soon became friends again. Later that year, the artists broke up during the terrible siege of Paris in the Franco-Prussian War when Manet joined the National Guard to defend his city. This was followed by a civil war that interrupted the artist's career, although he did make several sketches of the ghastly realities of war.

Growing Recognition

The 1870s was a good decade for Manet after the troubles of the war. Over 30 of his works were bought by the French art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (1831-1922) and these greatly appreciated in value as Manet's reputation grew. Durand-Ruel organised an exhibition in London, and the 1872 Salon showed two of Manet's paintings, Battle of Kearsage and Alabama. He became close to Monet, and although Manet was little interested in light per se, his work began to show an impressionist influence, particularly in the use of brighter colours. Le Bon Bok (The Beer Drinker), a vibrant portrait, was accepted by the 1873 Salon and met with wide acclaim. The costs of his large new studio were helped by the commission of Races at the Bois de Boulogne.

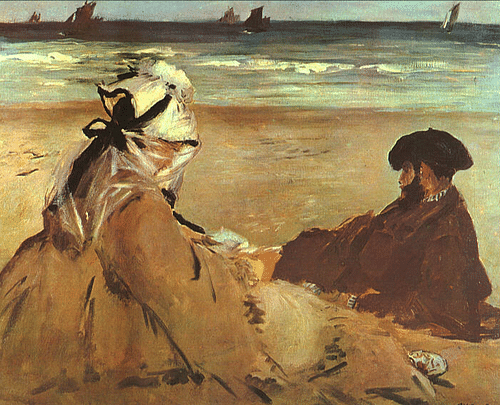

Another influence of the impressionists on Manet was the idea of painting outdoors – plein air – as opposed to sketching a scene and then painting it in the studio. Manet practised the technique for several seascapes at Boulogne in 1873 and with Monet at Argenteuil on the Seine in 1874. The technique requires quick light strokes and can be seen in his Sur la Plage (On the Beach). The painting has a lighter colour palette, but Manet still finds space for his beloved black in the man's clothing. The less-impressionistic Argenteuil was shown in the 1874 Salon. More forays into plein air painting occurred during Manet's visit to Venice in 1875.

Manet's work could still puzzle. The Railway Station, accepted by the Salon in 1874, has two figures who are not interacting, the girl even has her back to the viewer. The title was a misnomer since no station is shown, only the steam of the trains. The work is perhaps indicative of Manet's drift towards the style that would later become known as symbolism – a rejection of realism for more humble subjects presented in a way that provoked the imagination and emotion of the viewer. Following rejections for the 1875 Salon, Manet organised his own exhibition with the invitation cards printed with his personal motto: Faire vrai et laisser dire ("Make it truthful and let others say what they like"). 4,000 people came to his studio, but none were buyers. Another shocking courtesan portrait, Nana, was rejected by the Salon in 1877 but displayed in a dealer's shop where it gained notoriety.

Manet's health was now failing from the effects of syphilis, which often confined him to his studio. He returned to painting Parisians in the city, at the races, and on water. His Boating (1874) and In the Conservatory (1878) were both accepted for the 1879 Salon. In 1880 he had a solo exhibition organised by Georges Charpentier, a publisher. Two more pictures were accepted by the Salon, including At Père Lathuilles, perhaps his favourite restaurant. In his confinement, Manet increasingly turned to still life, usually the flowers that were sent to him daily by friends. In 1881, he finally gained recognition from the Salon when he won second prize for his rather conventional portrait of the politician Henri Rochefort, an award that meant any of his subsequent entries would now be automatically accepted (although he was too ill to ever submit again). The cherry on the cake came when Manet's life-long friend Antonin Proust became Minister of the Fine Arts and awarded the artist the Légion d’Honneur.

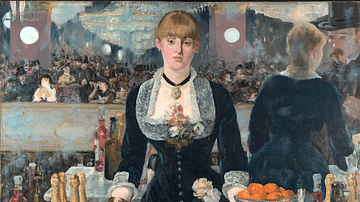

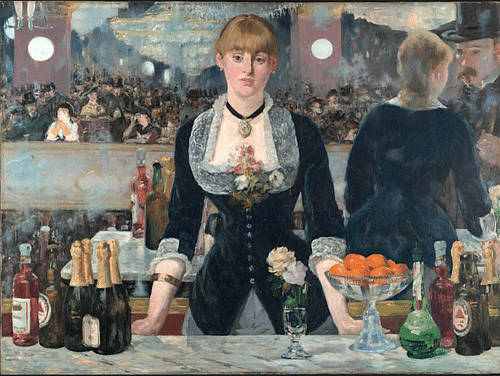

Also around 1881, Manet reached what many regard as his artistic summit: the iconic Bar at the Folies-Bergère. Showing a barmaid stood behind her bar, the background is a mirror that reflects the shows for which this fashionable grand café was famous. It shows Manet's move away from realism – the barmaid's reflection is impossible – and, instead, he provokes an emotional reaction from the viewer. He captures a woman unhappy with her work as the gay life of the customers goes on behind her in reflection. There is even a characteristic Manet touch, the comedy of the acrobat's feet in the top left corner. This masterpiece is Manet's last farewell to the Parisian café life he loved so well.

Legacy

Manet's illness caused gangrene in his left leg, which was amputated; the artist died from the operation on 30 April 1883, aged 51. He was buried in Passy Cemetery in Paris. Official recognition continued, notably with the acceptance of Olympia by the Louvre and exhibitions in the United States and elsewhere. Manet's work, especially his choice of humble daily life and preoccupation with deliberately flattening the scenes, influenced his contemporaries and a generation of younger artists that included Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901), and Henri Matisse (1869-1954). At Manet's funeral, his old friend Degas noted regretfully that "he was greater than we thought" (Thomson, 209).