Edward the Confessor, also known as Saint Edward the Confessor, reigned as king of England from 1042 to 1066 CE. Edward was reliant on the powerful Godwine (aka Godwin) family to keep his kingdom together but his achievements included a relatively peaceful reign in a turbulent century for England and the foundation of Westminster Abbey. With no children, Edward's successor was Harold Godwinson, aka Harold II (r. Jan-Oct 1066 CE) who would have to defend his right to the throne against several rivals, most dangerous of whom was Edward's distant cousin William the Conqueror (l. c. 1027-1087 CE). Seen by many later rulers as the spiritual founder of the English and now British monarchy, Edward was made a saint in the 12th century CE, and his crown (or surviving parts of it) is still used in the British coronation ceremony.

Succession

Edward was born c. 1003 CE at Islip in Oxfordshire, the son of King Aethelred II (aka the Unready, r. 978-1016 CE) and Emma of Normandy (c. 985-1052 CE). Edward's brother was Edmund Ironside who had briefly reigned as king in 1016 CE until his death that year in November. In the rather messy dynastic happenings of pre-conquest England, Edward succeeded King Harthacnut (r. 1040-1042 CE), the son of King Cnut (r. 1016-1035 CE) and brother of King Harold I (r. 1040 CE). Harthacnut had died of a seizure without an heir on 8 June 1042 CE. Edward was Harthacnut's half-brother (they shared the same mother) and he had been in exile in Normandy for 25 years until the king had recalled him and set him up as both co-ruler and heir. Harthacnut had been an unpopular ruler because of his severity and excessive taxes, and his demise, probably caused by a drinking bout, was lamented by few.

By a chance of three kings all dying within seven years, then, Edward, who was now more Norman than English, unexpectedly found himself on the throne at age 40. The new king's coronation was held at Winchester Cathedral on 3 April 1043 CE. For a man who seemed to like hunting more than anything else, and whose character is sometimes described by historians as weak, his reign was to be largely peaceful, a situation greatly helped by the reduction in Viking raids, a victorious campaign against Macbeth, King of Scotland (r. 1040-1057 CE) in 1054 CE, and the successful containment of the rebellious Welsh in the 1060s CE. As it turned out, Edward's most dangerous enemies were not his neighbours but inside his own court.

The Godwines

Edward married Edith Godwin (aka Edith of Wessex or Eadgyth Godwin, d. 1075 CE) on 23 January 1045 CE, a handy alliance to the kingdom's most powerful family. Indeed, it was Edith's father, Godwin, the Earl of Wessex, who largely ensured Edward kept his throne from rival Scandinavian claimants descended from various of his predecessors. There was some friction between the two as Godwin preferred to promote Saxons into key court positions while Edward favoured Normans. Another embarrassment was the wild behaviour of Godwin's eldest son Earl Swegen (aka Swein) who infamously kidnapped the abbess of Leominster and then murdered her cousin, Earl Beorn. Things blew up in 1051 CE when the Godwines refused Edward's orders to intervene in a dispute between the townsfolk of Dover and the visiting Eustace of Boulogne where a fracas had occurred and one of Eustace's men was killed. Edward organised a trial, the result of which was prominent members of the Godwines family were banished to Ireland, and the king even sent his wife Edith to a convent.

The Godwines were not keen to give up their lands, and when they returned in force to England just one year later, it looked like civil war would erupt. Fortunately, the Witan, the king's council of advisors, encouraged Edward to give the Godwines back their lands and titles. The Godwines proved too powerful and their followers too loyal for the king to sideline them for any length of time. Edith was brought out of her confinement and took her rightful place as queen again.

After Earl Godwin died on 12 April 1053 CE, his son Harold Godwinson (b. c. 1023 CE) inherited his title as Earl of Wessex and role as leader of the family and most powerful military commander in England (Earl Swegen having died on a pilgrimage to the Middle East). Harold's brothers were also powerful men in the kingdom: Tostig, Earl of Northumbria, and Gyrth, Earl of East Anglia. In order not to be completely dominated by the Godwins and ensure his earls had a more balanced distribution of land, King Edward insisted that Harold gave up East Anglia.

William of Normandy

It was around 1051 CE - significantly, when the Godwines were in exile and out of favour - that William, Duke of Normandy visited Edward. The man who became better known as William the Conqueror would later claim the English king had promised him the throne in gratitude for the hospitality the king had received in Normandy during his exile. The two were distantly related, Count Richard I of Normandy (l. 932-966 CE) being both Edward's grandfather and William's great-grandfather. It may also be true that Edward was happy to nominate William as his heir because it was only a contingency arrangement, that is, he intended to produce a son of his own, even if it meant remarrying. In addition, the favour given to William may have been a deliberate strategy to counterbalance the enormous power of the Godwines.

Another element to William's claim (at least according to Norman chroniclers), was that Harold Godwinson had visited Normandy in March 1064 CE, where he had been captured by Count Guy of Ponthieu and then handed over to William. The medieval sources are unclear or conflicting as to why Harold sailed from Bosham in Sussex in the first place. Some say his ship was blown off course in a storm, others that he intended to meet William in Normandy to inform him the Norman was Edward's nominated successor, and still others that Harold was attempting to release English prisoners held in Normandy.

According to pro-William sources such as William of Poitiers (c. 1020-1090 CE), a condition of Harold's release was that Harold promised to become William's vassal and prepare the way for an invasion of England. All of this may merely have been a justification for William to invade England in 1066 CE, and the Anglo-Saxon sources dispute much of the story. As it turned out, according to the Anglo-Saxon sources, on his deathbed Edward selected Harold Godwinson, who had become his closest advisor, as his successor.

Harold had indeed been using his time well. He proved himself a useful leader for the king, building his reputation on such successful military conquests as the attack on Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, King of Wales in 1063-4 CE, after which he was widely applauded as the subregulus (under-king) and dux Anglorum (commander-in-chief of the English). In 1065 CE Harold had also sorted out a rebellion in Northumberland caused by his own brother Tostig's harsh rule there. Tostig was banished to Flanders, and there were rumours that Harold had engineered the whole episode in order to gain even greater favour with King Edward. In short, Harold Godwinson, brother-in-law to the king, was the man of the moment in England, and it is perhaps no surprise that Edward, without children of his own, selected him as his heir even if he had favoured Duke William 15 years earlier.

Westminster Abbey

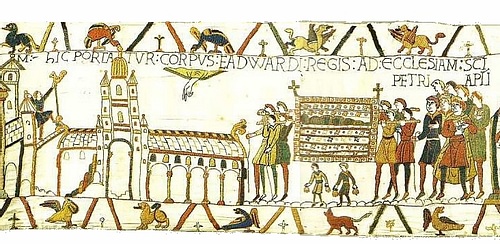

Edward famously founded Westminster Abbey in London, which was dedicated to Saint Peter and consecrated in December 1065 CE. Unfortunately, Edward was too ill to attend the ceremony. The Abbey, built in the Norman Romanesque style, was the largest in England and one of the finest in Europe; it would host coronations from 1066 CE onwards, starting with that of William the Conqueror. The abbey's choice of location also began the process of shifting the political capital of England away from Winchester to London. The Abbey was inhabited by Benedictine monks until 1640 CE, became the burial place of monarchs and luminaries, and was rebuilt many times over the centuries. A sealed writ from the king survives and notes the handing over of the estate of Perton for the abbey's use. Edward also encouraged the trend of church-building elsewhere, ensuring nobody in his kingdom lived very far from one. The king was busy, too, with castles, building many of them in Herefordshire in western England to meet the threat of Welsh rebellion. These castles, like William the Conqueror's more famous fortifications, were mostly structures made from wood and earth.

Death & Successor

Edward, then around 62 years of age, died on 5 January 1066 CE at Westminster, and he was, appropriately enough, interred in his new abbey. On 6 January 1066 CE Harold Godwinson was crowned Harold II of England, probably also in Westminster Abbey. The speed with which Harold had himself crowned is perhaps indicative of the challenges he faced from rivals other than Duke William. The most dangerous rival was Harald Hardrada, king of Norway (aka Harold III, r. 1046-1066 CE) whose highly dubious claim to the English throne was based on his belief he was the rightful ruler of Denmark which had once controlled areas of England and the fact that his own predecessor, Sweyn (Swein) of Norway, was an illegitimate son of Aelfgifu, wife of King Cnut. The other rival was Edgar the Aetheling, grandson of Ethelred II and great-nephew of Edward the Confessor, but he was only in his early teens in 1066 CE and so easily sidelined, especially as the nobles of England feared attacks from abroad and needed now a leader with military prowess.

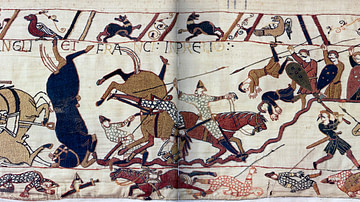

Harold's reign would be short indeed. First, he had to face an invading army in the north of England led by Harald Hardrada and Harold's exiled brother Tostig. Harold was victorious at the Battle of Stamford Bridge on 25 September but then had to turn south and meet William the Conqueror's army at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066 CE. Harold was killed in that battle and William began his successful Norman Conquest of England. The Norman duke was crowned William I on Christmas day 1066 CE, again in Westminster Abbey, and he would reign until 1087 CE.

Legacy - Sainthood & Crown

Edward the Confessor has cast a long shadow over English history for a king with such an uneventful reign. Domesday Book, the survey and record of all the landowners, property, tenants, and serfs of medieval England, was compiled in 1086-7 CE but recorded the situation of ownership at the end of Edward's reign in January 1066 CE. Edward appears several times in that other great Norman record, the Bayeux Tapestry (1067-1079 CE) which presents a pictorial history of the Norman conquest. Edward's fame would continue on in many other ways, too. Edward became the very symbol of pre-conquest England. He was made a saint by the medieval Church in 1161 CE for his great piety (of which there is not much evidence) and given his title 'Edward the Confessor' in a probably mistaken belief that his marriage was childless because he had taken a vow of celibacy. Saint Edward's feast day was selected as 13 October.

The king was made the patron saint of England for a time, standing alongside Saint George in that exalted position, and his reign, seen as a golden age when a just monarch ruled wisely, inspired the 12th-century CE law code the Laws of Edward the Confessor. Besides all future monarchs having to swear to uphold the laws of Saint Edward at their coronation, Edward specifically inspired several later English kings such as Henry III of England (r. 1216-1272 CE) and Richard II of England (r. 1377-1399 CE) who both regarded the saint as a figure of admiration, the former even building him a magnificent new shrine in Westminster Abbey and being a major factor in his canonisation.

Edward continues to be commemorated by each of his successors as one of the crowns of the British Crown Jewels, the St. Edward's Crown, has often been used during the coronation ceremony of British monarchs (and even if a substitute crown is used it is still called St. Edward's Crown for the purposes of the ceremony). Henry III, when building his shrine to his illustrious predecessor, likely removed robes, jewels, and the gold Saxon crown or diadem from Edward's coffin to incorporate them into his new royal regalia. The Crown Jewels were destroyed or sold off in 1649 CE following the execution of Charles I of England (r. 1600-1649 CE) but some pieces were reacquired and incorporated into the new regalia of 1660 CE following Restoration of the monarchy and coronation of Charles II in 1661 CE (r. 1660-1685 CE). The solid gold St. Edward's Crown was made for this coronation and, weighing 2.3 kilos (5 lbs), it possibly includes pieces from Edward's original crown.

Finally, the oldest of all the Crown Jewels items is considered to be St. Edward's Sapphire, an octagonal rose cut stone, said to have been taken from the ring of Edward the Confessor. This stone is now set in the top cross of the Imperial State Crown, which was made in 1838 CE for the coronation of Queen Victoria (r. 1837-1901 CE). The story goes that King Edward once gave the ring away to a beggar, but it was returned to him by two pilgrims. These pilgrims had miraculously met Saint John the Evangelist in Syria who had explained that he had been the beggar in disguise. Such are the tales of this king which spread and grew through the late Middle Ages.