Elves and dwarves represent minor divine figures in Norse mythology. Elves (álfar) and dwarves (dvergar) have in common their talent for creating precious objects, skill, agility, and moral ambiguity. Dwarves appear in several important stories, such as the one about the forging of Thor’s hammer, or dragon Fafnir’s treasure. Elves, on the other hand, accompany the gods in poetry but do not really have individual stories, except for Völund the smith.

Influenced by later folklore and popular culture, we tend to think about elves, dwarves, and many other supernatural beings as having certain characteristics which makes them very easily identifiable. However, for pagan Northmen, the lines drawn between these creatures must have been much blurrier than it is for us. We should remember as well that besides elves and dwarves, the imaginary space was also populated by landsvættir, spirits of the land who can both bless and curse travellers; valkyries, the helpers of Odin in picking warriors for his hall; disir, some kind of guardian spirits; trolls, a term used to describe evil spirits or magical mountain-dwellers; and even undead creatures called draugar.

The Origin of the Dwarves

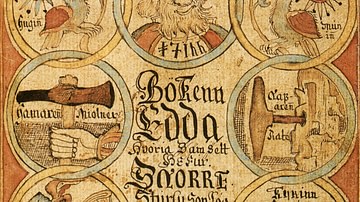

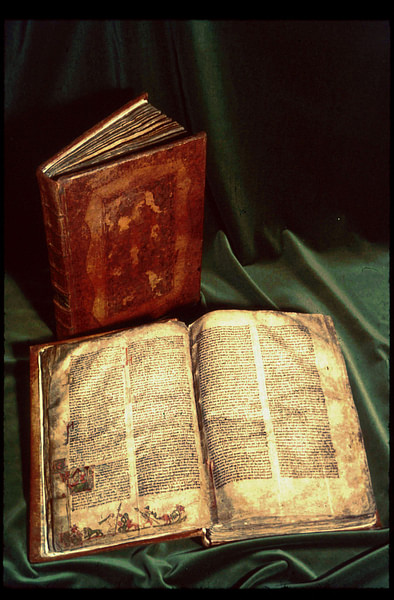

In folklore, dwarves are generally associated with craftsmanship, mining, mountains, earth, and their appearance does not seem too enticing. It is implied that they are shorter by the use of the phrase "dvergr of voxt", "short like a dwarf". Dvergar can shapeshift and sometimes get quite vicious. There is little in Norse sources on other physical traits; their forging talents do seem to put them in the limelight. Details on their origin are found in the creation poem Völuspá, the first poem of the Poetic Edda, the 13th-century CE collection of Norse poems. In stanza 9, the gods gather and decide who should lead the dwarves "out of Brimir’s blood and the legs of Blain" (Hildebrand, 16), two names possibly synonymous with Ymir or his flesh.

In stanza 10, we have the names of two apparently powerful dwarves, Motsognir and Durin, but little is known of them, as with the other dwarves listed in the following catalogue up to stanza 16, the Dvergatal in Old Norse. J.R.R. Tolkien used this catalogue as inspiration, particularly the names Gandalfr ("magic elf", not dwarf) and Eikinskjaldi. Moreover, he too describes the dwarves as Durin’s folk. Among the many names, we also find Norþri, Suþri, Austri, and Vestri – north, south, east, and west, the ones holding the sky up. The race of dwarves, down to a character named Lofar, leaves the mountains for a new home, but this story is unexplained. Another name in the list, Dvalin, is credited in another poem of the Poetic Edda, the Hávamál, with having given some magic runes to his kin, which perhaps explains their skills (stanza 144).

The medieval Icelandic author Snorri Sturluson, who wrote The Prose Edda, states that they came out of the primordial giant Ymir’s flesh like maggots, and then the gods endowed them with reason. They can live in soil or in rocks. The short narrative called Sörla þáttr, where the goddess Freyja sleeps with some dwarves in exchange for a magnificent collar, also states that they live in rocks or likely caves. To complicate things even more, Snorri makes a difference between light-elves who live in a splendid place called Alfheim and dark-elves (svartálfar) from the ground, who might be the same as or related to dwarves.

In the poem Fáfnismál of the Poetic Edda, the dragon killed by the legendary hero Sigurd mentions that some of the Norns, the deities who have the gift of prophecy and decide the fates of all, are from the family of Dvalin. Generally, however, most dvergar are male. Some turn into animals, for example, the aforementioned Fafnir from the legend of the clan of the Volsungs (related to the continental cycle of Nibelungs), Andvari who lives like a fish, and Otr, which means quite literally an otter, from the same story.

Dwarven Gifts

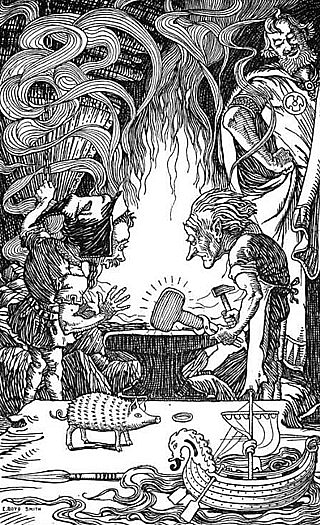

The tale of the making of Mjölnir, Thor’s hammer, and of other essential items has only been transmitted by Snorri’s Edda, the secondary source, but because they are sometimes used in metaphors in poetry, they probably come from older sources. In the Skáldskaparmál ("Language of poetry"), Snorri tells us this tale as an answer to the question of why Sif’s hair is called gold. Sif, Thor’s wife, has her hair cut off by Loki as a prank. Infuriated, Thor forces Loki to look up the black-elves/dwarves to make her hair of gold. Loki goes to the sons of Ivaldi, who also create Gungnir, Odin’s spear, and Skidbladnir, Freyr’s ship. Loki wagers his head with another dwarf called Brokk that he and his brother Eitri would not be able to make three objects as precious as these.

When they get to the task in their workshop, Loki in the form of a fly starts troubling Brokk, but he keeps blowing in the forge. At some point, he stops to sweep the fly away as it has been nibbling his eyelid, which is why the hammer they make for Thor comes with a defect, that it is rather short. They bring it to the gods, together with the ring Draupnir, which drips nine other rings every ninth night, and Gullinborsti, a magic boar faster than any horse. About the hammer Mjölnir, they say it would not fail in any strike. After it is decided that this is indeed the greatest gift, Brokk has Thor catch Loki for him, but the deceitful Loki says he wagered his head, not his neck, and the dwarf's brother Alr seals Loki's lips.

Major Characters

Two wicked dwarves named Fjalar and Galar come up in the story of the mead of poetry. They are the ones who kill Kvasir, the extraordinary knowledgeable creature born out of the mixed spit of the two families of gods, the Æsir and the Vanir, when they end their war at the beginning of the world. After they kill him, they drain his blood, mix it with honey, and thus concoct the mead of poetry, the enchanted liquid that will turn anyone into a talented skald. Then the dwarves invite a giant named Gilling and his wife. As one day they go out at sea, the boat capsizes and Gilling drowns. Tired of his wife’s weeping, they drop a millstone on her head. Enraged by these mischievous acts, Suttung, the couple’s son seizes Fjalar and Galar but receives as compensation the magic mead. This is why poetry is sometimes called the dwarves’ drink.

Another noteworthy dwarven character is Alviss, literally "all-knowing", found in the poem Alvíssmál of the Poetic Edda. Thor compels him to answer his questions to prove his skill after the dwarf states that he was promised his daughter Throdr, and irritates him by calling him a vagrant due to his lack of refinement. Thor asks what the earth is called, the clouds, the wind, the sea, the fire, and so on. Interestingly, the elves appear in eleven answers about naming these elements, as the poem seems to draw a line between these races. In the end, Thor admits the wealth of wisdom he has witnessed, but the conversation proves to be a trick to make him wait until the sunlight turns him into stone.

Thirdly, we have those characters from the story of Sigurd. The Volsunga saga was written in the 13th century CE, and it makes use of plenty of supernatural motifs. Before the adventures of Sigurd, the saga deals with the power struggles of Sigurd's ancestors. His father Sigmund is slain in a battle with a suitor of his mother Hjordis. She is taken in by Alf, prince of Denmark, and her son Sigurd turns out to be of extraordinary might and character. Regin, son of Hreidmar, acts as his foster father yet entices him to go on a quest that would trigger his impending doom. He tells him the story of his family and his two brothers, Fafnir and Otr, and how one day Odin, Loki, and Hoenir killed Otr in his otter shape.

Naturally, the king demanded compensation, which was given in the form of the gold taken from the dwarf Andvari, who cursed one item, the ring Andvararnaut. Fafnir killed their father, turned into a dragon, and hid all the treasure, while Regin became a smith. Thus Sigurd, after avenging his father first, accepts the challenge and stabs Fafnir in the heart while laying in a ditch he digs underneath, following Odin’s advice. Regin drinks Fafnir’s blood and asks Sigurd to roast his heart for him to eat. Wanting to test it, Sigurd begins to understand the speech of birds who talk about Regin’s plans to slay Sigurd. He, therefore, decides to kill his foster-father, eat some of the heart, and take much of the treasure.

Regin is also listed among the dvergar of the Völuspá. The Reginsmál only mentions his shortness but goes on to say that was fierce, skilled in magic, and wise, so this identification might work. However, he is also called a jotunn, a giant, at some point. Anyhow, both Regin and Fafnir succumb to their greediness, allowing the glittering gold to overcome their judgment. Talented smiths as they are, their creative power can turn against them.

The Legend of Wayland the Smith

Very little is known of the elves in Norse myth. Perhaps the god Freyr, connected to prosperity and good harvest, had something in common with them, as the poem Grímnismál suggests that the realm of the light-elves, Alfheim, has been given to him. In legendary sagas, kings of elven blood seem to be of higher importance. The elven sacrifice that the poet Sigvat briefly comments on in his poem Austrfararvísur might have been a feast related to good harvest and ancestor worship.

The most famous elf was Wayland the Smith (Völund in Old Norse, Wēland in Anglo-Saxon, Wieland in German) whose story must have circulated in various versions across the whole Germanic space. The figure is present in Old English as early as the 8th century CE, probably spreading in Scandinavia a century later. Völund is celebrated at length in the first heroic poem of the 13th-century CE Poetic Edda, namely Völundarkviða (Lay of Völund, Old Norse: Vǫlundarkviða), which tells of how the famous craftsman was lamed by king Nithuth and then enacted terrible revenge.

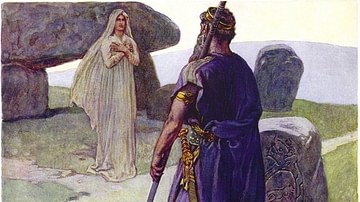

In the introduction, Völund is presented as a son of king Finni, possibly a reference to inhabitants of Lapland associated with magic in Norse sagas. This skillful figure together with his brothers take swan-maidens (valkyries) as wives, but after some years they fly away. While his brothers go searching for them, Völund stays home and forges rings with gems, waiting for his wife. As he is doing this, Nithuth hears about his whereabouts and sends his men to Völund’s hall when he is away. They see the 700 rings on a rope but only take one. Upon coming home, the "master of elves" (stanza 13) notices the missing one, thinking his wife Hervor has returned. After falling asleep, he is captured by Nithuth and charged with having stolen his treasure, but the elf says the gold was not in the hills of the Rhine. This piece of information indicated that the Norse story had a southern inspiration.

The king takes Völund’s sword, his daughter receives the gold ring meant for Völund’s wife, and the queen speaks of his bad appearance and upcoming unhappiness of this creature or Myrkwood (a magical place also used by Tolkien). She says that "his eyes are glowing like glistening snakes" and he "gnashes his teeth" when he sees the sword and ring , so they cut his hamstrings and place him on an island (Hildebrand, 359). There he crafts all kinds of precious objects for the king, never resting. One day Nithuth’s sons come to the island to see the elf’s great treasure. The second time they visit Völund kills them and hides their bodies under his bellows.

Cruelly vengeful, he makes silver cups out of their skulls for the king, gems out of their eyes for their mother, and a brooch out of their teeth for their sister Bothvild. The story continues after a gap in lines with Bothvild regretting that her ring has broken. Völund promises to fix it, and then they drink together and she falls asleep in his chair. Völund makes the princess her lover, who then weeps for her partner who manages to escape the island. After another gap and unclear lines in the poem, the king summons Völund, the "crafty elf" to explain to him what happened to his sons (Hildebrand, 367). Before confessing, the elf makes him swear no harm will come to his bride, Bothvild that is, and the child she is carrying. Much as Nithuth wishes to have his revenge, he cannot reach the elf: "no man is so tall as to take you from your horse, no archer so good to shoot you down there where you wander among the clouds" (Hildebrand, 369).

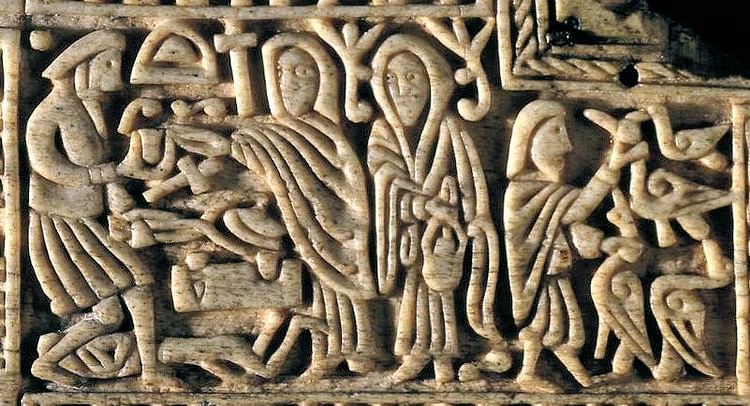

The story concludes with Bothvild confirming Völund’s sayings and the flight of the elf. The Lay of Völund does not explain how he manages to fly away, but we can draw on another source to infer that. In Thidrekssaga, a piece of medieval literature based on legends about Theoderic the Great, we find out that Egil, Völund’s brother, is the one who helps him shoot birds and make a feather costume. Egil is also the one compelled by Nithuth to shoot at Völund, but not before hiding a bladder filled with blood under his arm so that the king believes his enemy is killed. Furthermore, these details are suggested in scenes on the Franks casket of ivory, an 8th-century CE Anglo-Saxon chest rich in mythical subject matters.

Völund is a complex character, reuniting aspects of the light and dark elves mentioned by Snorri: at first peaceful and melancholic, then after his imprisonment aggressive and merciless. His most defining trait remains that of craftsmanship: his skillfulness brings him both fame and trouble, yet it helps him gain his freedom again. The fact that he has the looks of a serpent suggests a relationship to the earth, and Thidrekssaga adds that he has learned the art of forging from the dwarves. The legend of Völund/Wayland is to be found summarized in Deor’s Lament, a 10th-century CE Old English poem in the Exeter Book, when the suffering poet lists heroes who have also endured a lot of pain, among whom the elven smith. Other references to him come up in the poems Beowulf and Waldere, on a Swedish runestone in Ardre, and various traditions of medieval folklore.

Conclusion

Given their ability to produce exquisite objects and their knowledgeable, somewhat enchanted nature, we could suppose elves and dwarves occupied an intermediary place between gods and men. They have survived in modern folklore as part of the hludufólk, the hidden peoples. Medical texts, possibly under Christian influence, see them rather negatively, as demons. As remarked by Turville-Petre,

It is an old and widespread belief that elves cause illnesses, and Old English terminology is rich in expressions which show this. Ælfsiden is said to mean a nightmare, and ælfogoða, hiccoughs. Ylfagescot (elf-shot) is applied to certain diseases of men and beasts. (232).

The Anglo-Saxon poem Against a Dwarf is a charm supposed to cure an illness of some kind of trouble sleeping, a nightmare, "elf-dream" (Alptraum in German).

Regarding the differences between all these supernatural creatures, scholar Ármann Jakobsson adds:

Notions of a continuity of Northern folk traditions […] are revived in every generation, with subtle changes, without having ever really gone out of fashion. Even though arguments can be made for such a continuity in certain cases, it may be jeopardous to make general assumptions from only limited or specific instances. Each case must instead be judged on its own merit. Another fallacy would be to assume that we always know what medieval concepts and terminology signify because we know what the same words were used to indicate during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, without ever examining their actual usage in the medieval sources. (28)

Elves and dwarves were probably seen as interchangeable, belonging to the large family of spirits populating a world seen as much richer than what the naked eye could grasp, as Northmen did not share our passion for clear categories. It is also worth bearing in mind that they might have had different ideas about these beings than the images presented in folk tales now. It could be an interesting change of perspective now for those of your who rewatch Lord of the Rings, to imagine what Legolas would look like if he were more similar to Gimli.