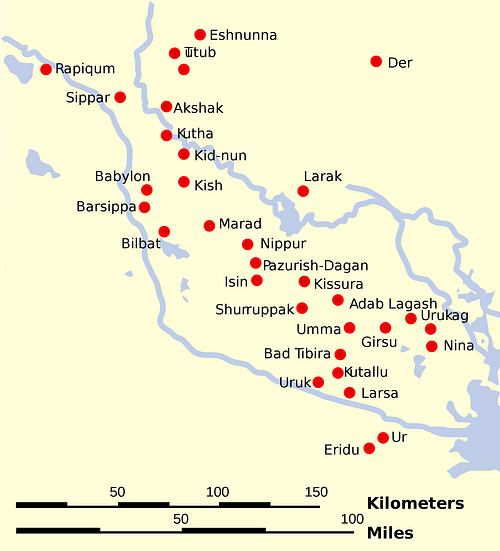

Eridu (present day Abu Shahrein, Iraq) was considered the first city in the world by the ancient Sumerians and is among the most ancient of the ruins from Mesopotamia. Founded in c. 5400 BCE, Eridu was thought to have been created by the gods who established order upon the earth with Eridu as the starting point.

The city was home to the great god Enki (also known as Ea by the Akkadians) who would develop from a local god of fresh water into the god of wisdom and magic (among other attributes) and stand with other deities such as Anu, Enlil, and Inanna as the most important in the Mesopotamian Pantheon. As Enki's home, it became associated with many of the most vital myths of Mesopotamia including those concerning an early paradise-on-earth.

The Sumerian King List cites Eridu as the “city of the first kings”, stating, “After the kingship descended from heaven, the kingship was in Eridu” and the city was looked back upon by the various city-states of Mesopotamia as a metropolis of a 'golden age' in the same way the writers of the biblical narrative of Genesis created a 'Garden of Eden' as their mythical paradise, most likely modeled on Eridu. The city was abandoned in c. 600 BCE, probably due to overuse of the land, and fell into ruin.

The First City

The city of Eridu features prominently in Sumerian mythology, not only as the first city and home of the gods, but as the locale to which the goddess Innana traveled in order to receive the gifts of civilization which she then bestowed upon humanity from her home city of Uruk. Uruk vies with Eridu among modern scholars for the honor of the oldest city in Mesopotamia or even the oldest in the world.

The ancients certainly believed Eridu to be the first city and the Sumerian King List gives impossibly long reigns (some between 28,000-36,000 years) for their kings while Sumerian scribes maintained that kingship in the land first came from heaven to be established at Eridu. Scholar Stephen Bertman writes:

Tradition made it the earliest city to have a king before the days of the mythical Great Flood. Eridu's archaeological story can be traced back to at least the sixth millennium BCE. If the tradition of its antiquity is true, Eridu may well have been the first city on earth. (19)

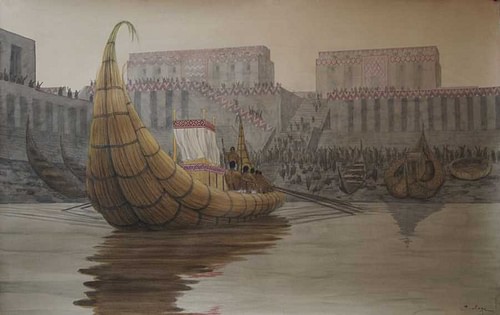

If not the first, the city was among the oldest. The ancient Mesopotamians frequently built their cities ontop of the ruins of older settlements (as is also true of other cultures). Excavations at Eridu have revealed a sequence of construction dating back to the Ubaid Period (c. 5000-4100 BCE) and continuing on from there to reach its height during the Ur III Period (2047-1750 BCE) under rulers such as Ur-Nammu (r. 2047-2030 BCE) and Shulgi of Ur (r. 2029-1982 BCE) both of whom encouraged trade from the city, both long-distance and local. Glass from Eridu has been found in the ruins of the cities of Egypt.

At the same time, however, the city was never a powerful political site. Scholar Gwendolyn Leick notes how "Eridu was never the seat of a dynasty. It's importance was religious rather than political, as the site of the main sanctuary of Enki" (62). Enki, the god of wisdom, featured prominently in many Mesopotamian texts and especially in the tale of the Great Flood as told in the Atrahasis and the Eridu Genesis.

Enki and Eridu

Eridu, as noted, was the home of Enki and the center of his cult. Bertman comments on the ruins of Enki's temple:

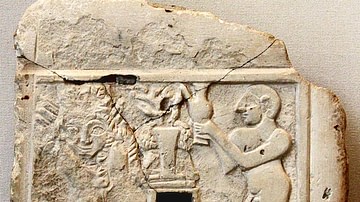

The god's temple has been found and shows that it was rebuilt over the course of thousands of years. In its earliest phase (dating back to about 5500 BCE), it masured abourt 12 by 15 feet, was made of mud brick, and featured a simple podium or altar for sacrifices and a niche meant to hold a statue of the god. To judge by evidence found in a later niche - fish bones and ashes scattered on the floor around the altar - the god's favorite meal was freshwater fish. The temple's antiquity makes it the oldest in Mesopotamian architectural and religious history. (20)

Enki was associated with fresh water, as was Eridu itself since it was located in the southern marshes of the Euphrates River, and so it is no surprise that both Enki and Eridu feature in the earliest of the Great Flood stories from which the later tale of Noah and his Ark was developed. The Eridu Genesis (composed c. 2300 BCE) is the earliest description of the Great Flood, pre-dating the biblical book of Genesis, and is the tale of the good man Utnapishtim (also known as Atrahasis or Ziusudra) who builds a great boat by the will of the gods and gathers inside 'the seed of life' at Enki's suggestion. Enki was instrumental in the creation of humanity and when Enlil, King of the Gods, grew tired of humanity's noise and decided to destroy them, it was Enki who preserved life on earth by saving Utnapishtim and life on earth.

The Eridu Genesis may have been the first written record of a long oral tradition of a time around 2800 BCE when the Euphrates rose high above her banks and flooded the region. Excavations at Ur by Leonard Wooley in 1922 revealed an eight-foot layer of silt and clay, consistent with the sediment of the Euphrates, which seemed to support the claim of a catastrophic flood in the area around 2800 BCE. Notes of the excavation taken by Wooley's assistant, Max Mallowan, however, showed the event was clearly a local, not a global, event.

A proto-Genesis tale of the Garden has been found at Eridu in which Tagtug the Weaver (or gardener) is cursed by Enki for eating of the fruit of the forbidden tree in the garden after being told not to. Eridu is further associated with the tale of the great sage Adapa (son of Enki), who was initiated into the meaning of life and all understanding by the god of wisdom but was ultimately tricked by him and denied the one thing he most wanted: knowledge of life without death, to live forever.

The desire for immortality features prominently in Mesopotamian literature, and Sumerian writings specifically, and is epitomized in the story of Gilgamesh of Uruk. Uruk's link to Eridu is significant in that Eridu's initial importance was later eclipsed by the rise of Uruk. This transferrence of power and prestige has been seen by some scholars (Samuel Noah Kramer and Paul Kriwaczek among them) as the beginnings of urbanization in Mesopotamia and a significant shift from the rural model of agrarian life to an urban-centered model. The story of Inanna and the God of Wisdom, in which the goddess of Uruk takes away the sacred meh (gifts of civilization) from Enki, the god of Eridu, can be seen as an ancient story symbolizing this shift in the paradigm of Sumerian culture. The prosperous commercial center of Uruk superceded the rural Eridu.

Eridu as Babel

Even so, Eridu was an important center for trade as well as religion and, at its height, was a great 'melting pot' of cultures and diversity, as evidenced by the various forms of artistry found among the ruins. Under the reigns of Ur-Nammu and Shulgi, the city prospered. Bertman writes:

The citizens of ancient Eridu were [justly] proud of another structure [besides Enki's temple]: a mighty ziggurat dedicated around 2100 BCE by Ur-Nammu, king of Ur, and his son. Though its eroded platform stands only about 30 feet today, its base of oven-baked brick measures over 150 by 200 feet and once supported a far more imposing structure. (20)

The great Ziggurat of Amar-Suen (r. 1982-1973 BCE), son of Shulgi of Ur, in the center of the city has been associated with the Biblical Tower of Babel from the Book of Genesis and the city itself with the Biblical city of Babel. This association springs from archaeological discoveries which support the claim that the Ziggurat of Amar-Suen more closely resembles the description of the biblical tower than any description of the ziggurat at Babylon.

Further, the Babylonian historian Berossus (l. c. 200 BCE), who was a major source for later Greek historians, seems to be clearly referring to Eridu when he writes of 'Babel' as `Babylon'. His `Babylon' is in the southern marshes of the Euphrates and is patronized by the god of wisdom and fresh water. This association strongly suggests that Eridu is the original biblical Babel as the story of the great Ziggurat of Amar-Suen was most likely passed down orally before Berossus set the legendary structure down in writing.

Conclusion

Eridu was abandoned intermittently over the years for reasons which remain unclear and, finally, left behind completely sometime around the year 600 BCE. The cause is most likely overuse of the land. Scholar Lewis Mumford, who has studied the phenomenon of the city both ancient and modern, points out that a city will decline when it is "no longer in a symbiotic relationship with its surrounding land" (6). This is no doubt what brought down many, if not most of the great cities of Mesopotamia that were not destroyed in conquest.

As a popular religious and trade center, Eridu no doubt attracted many people as pilgrims and merchants, not to mention its citizens, and so the drain on the surrounding resources could have been quite significant and, finally, simply too much for the populace to endure. It is possible, even likely, that the city was periodically abandoned to allow the land to recover. Whatever the reason for its final abandonment, the ruins of Eridu today are largely wind-swept sand dunes. Very little now remains to remind a visitor of the once mighty city which was thought to be founded and loved by the gods.