The Sumerian Flood Story (also known as the Eridu Genesis, The Flood Story, Sumerian Creation Myth, Sumerian Deluge Myth) is the oldest Mesopotamian text relating the tale of the Great Flood which would appear in later works such as the Atrahasis (17th century BCE) and The Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 2150-1400 BCE).

The tale is also – most famously – told as the story of Noah and his ark from the biblical Book of Genesis (earliest possible date c. 1450 BCE, latest, c. 800-600 BCE). The story is dated to c. 1600 BCE in its written form but is thought to be much older, preserved by oral tradition until committed to writing.

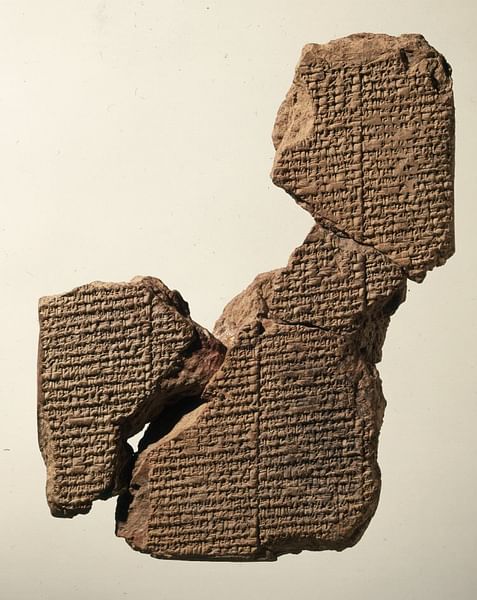

The extant work is badly damaged, with a number of significant lines missing, but can still be read and easily understood as an early Great Flood story. Scholars who have studied the text generally rely on the later Akkadian/Babylonian Atrahasis – which tells the same tale – to fill in the blanks of missing text from the broken tablet. The story most likely influenced the Egyptian “flood story” known as The Book of the Heavenly Cow (dated, in part, to the First Intermediate Period of Egypt, 2181-2040 BCE) but certainly was the inspiration for the later Mesopotamian works as well as the biblical narrative of Noah.

The story was first discovered in 1893, during the period of widespread expeditions and excavations throughout Mesopotamia funded by Western institutions. The good man in this version of the tale, chosen to survive the flood and preserve life on earth, is the Priest-King Ziudsura of the city of Suruppak (whose name means “life of long days”). This same figure appears in The Instructions of Shuruppag (c. 2000 BCE) and as Atrahasis (“exceedingly wise”) in the later work that bears his name, as Utnapishtim (“he found life”) in The Epic of Gilgamesh, and as Noah (“rest” or “peace”) in the Book of Genesis.

Expeditions & Discovery

In the 19th century, western institutions, including museums and universities, funded expeditions to Mesopotamia in hopes of finding physical evidence which would corroborate the historicity of biblical narratives. The 19th century saw the unprecedented practice of increasingly critical readings of the Bible which questioned long-held beliefs regarding its divine origin and supposed infallibility.

This age of skepticism would see the publication of Darwin's Origin of Species in 1859 suggesting that human beings, rather than created by God as “a little lower than the angels” (Psalm 8:5), evolved from primates. In 1882, the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche published his work The Gay Science, containing the famous line, “God is dead and we have killed him”, alluding to the seeming triumph of technology and secularism over traditional religious belief.

Prior to the rise of secular skepticism, and even during the period when Darwin and Nietzsche were writing, the Bible was considered the oldest book in the world, completely original, and of divine origin. This view was encouraged by the work of the archbishop James Ussher (l. 1581-1656), creator of the Ussher Chronology which, relying primarily on the Book of Genesis and referencing other biblical narratives, dates the creation of the world to 22 October 4004 BCE at 6:00 pm. Since the Bible was believed to have been written by God, it was infallible and could be trusted not only in dating the age of the earth but for any other aspect of human existence.

The expeditions sent to Mesopotamia were supposed to find evidence supporting this view but found the exact opposite. Cuneiform tablets, deciphered from the mid-19th century onwards, challenged the traditional view of the Bible directly in that they contained a number of stories, motifs, and symbols which appeared in the biblical narratives and predated them; among these was the Sumerian Flood Story, the first known account of the tale people of the time knew as Noah's Ark.

The badly damaged tablet was discovered in the ruins of the ancient city of Nippur by an expedition funded by the University of Pennsylvania in 1893. It was left untranslated until 1912 when the German Assyriologist Arno Poebel (l. 1881-1958) deciphered it as part of his job for the University of Pennsylvania. The existence of a pre-biblical account of Noah's Flood - already made clear by George Smith's translation of The Epic of Gilgamesh in 1876 - suggested to some that the traditional interpretation of the Bible needed to be rethought while, to others, that a Mesopotamian account of a great flood corroborated the biblical story, just from another point of view.

The British archaeologist Sir Leonard Wooley (l. 1880-1960) challenged this latter claim through his excavations at the ruins of ancient Ur in the 1920s. During the 1928-1929 excavation season, Wooley sank a series of shafts into the soil and determined there had been significant flooding in the region but that this was a local, not a global, event and, further, was not a singular incident but had happened a number of times when the Tigris and Euphrates rivers overflowed their banks.

Wooley's excavations were mirrored elsewhere in Mesopotamia by other archaeologists who came to the same conclusion. The historicity and originality of the biblical narrative of the Great Flood could no longer be maintained and Ussher's Chronology was challenged and dismissed by scholars (although both are still maintained by Christians in the present day who maintain the so-called Young Earth View). Scholar Stephanie Dalley, commenting on further excavations in Mesopotamia throughout the 20th century, writes:

No flood deposits are found in third-millennium strata, and Archbishop Ussher's date for the Flood of 2349 BC, which was calculated using numbers in Genesis at face value and which did not recognize how highly schematic Biblical chronology is for such early times, is now out of the question. (5)

The small tablet of the Sumerian Flood story found at Nippur, missing much of its narrative, had provided Wooley with the academic freedom to make the kind of assertions concerning the flood in the 1920s which would have been unthinkable a mere century before.

Summary

The Sumerian Flood Story begins with the creation of the world, the "black-headed people" (the Sumerians), and then the animals. The Sumerian gods who undertake the act of creation – An (Anu), Enlil, Enki, and Ninhursag – would remain among the most powerful Sumerian deities for centuries until they were eclipsed by Amorite theological paradigms under Hammurabi of Babylon (r. 1792-1750 BCE) and, later, the Assyrians.

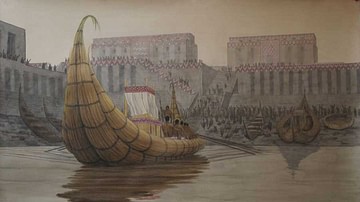

After humans and animals are created, the gods decree the establishment of cities, beginning with Eridu which was considered the oldest city in the world. Each of the cities are given to a god to oversee – thereby establishing the tradition of every city having its patron deity – and reference seems to be made to the further establishment of irrigation systems.

After this section of the narration, a number of lines are missing which must have explained why the gods An and Enlil – the leaders of the Sumerian pantheon - decide to destroy humanity with a great flood. In the later Atrahasis, the reason is that people become too numerous and too loud and disturb Enlil's rest. In Atrahasis, Enlil sends a drought, then a plague, and then famine to the earth to decrease the population and quiet the roar of the humans but, each time, Enki (god of wisdom and friend of humanity) tells the people what they should do to reverse Enlil's plagues and they are able to go on with their lives as before. It is probable these details also appeared in the earlier Sumerian Flood Story where Enki has the same role.

The narrative resumes with a depiction of the flood, which rages for seven days and seven nights, until the seas quiet and Utu (Utu-Shamash, the sun god) appears. Ziudsura makes a hole in the side of the boat, and Utu, in the form of the sun's rays, enters. Ziudsura dutifully makes a sacrifice to the god but what happens after is lost through more missing lines. In the end, An and Enlil seem to have repented of their decision as they are grateful that Ziudsura has preserved their creations. They grant him eternal life in the paradise of the land of Dilmun. Based on fragments of the tablet, it seems the story continued after this seeming conclusion for another 39 lines, but the content is lost.

Text

The following text comes from The Literature of Ancient Sumer, translated by the scholars Jeremy Black, Graham Cunningham, Eleanor Robson, and Gabor Zolyomi. The opening line referencing stopping “the annihilation of my creatures” might be suggesting that the gods initially gave human beings long lifespans as co-workers with the gods who would take on their labor and make the earth pleasant for them, as the story is given in Atrahasis.

In the Atrahasis, after the flood, measures are taken by the gods to limit the human lifespan and increase mortality and these kinds of details may have made up the missing text from the earlier Sumerian Flood Story which follows:

I will stop the annihilation of my creatures, and I will return the people from their dwelling grounds. Let them build many cities so that I can refresh myself in their shade. Let them lay the bricks of many cities in pure places, let them establish places of divination in pure places, and when the fire-quenching…is arranged, the divine rites and exalted powers are perfected and the earth is irrigated, I will establish well-being there.

After An, Enlil, Enki, and Ninhursag had fashioned the black-headed people, they also made animals multiply everywhere, and made herds of four-legged animals exist on the plains, as is befitting. [Here there are approximately 32 lines missing]

I will oversee their labor. Let…the builder of the Land, dig a solid foundation.

After the…of kingship had descended from heaven, after the exalted crown and throne of kingship had descended from heaven, the divine rites and the exalted powers were perfected, the bricks of the cities were laid in holy places, their names were announced and the…were distributed. The first of the cities, Eridu, was given to Nudimmud the leader. The second, Bad-tibira, was given to the Mistress. The third, Larag, was given to Pabilsag. The fourth, Zimbir, was given to hero Utu. The fifth, Suruppag, was given to Sud. And after the names of these cities had been announced and the…had been distributed, the river…was watered. [Here there are approximately 34 lines missing]

…seat in heaven…flood…mankind. So he made…Then Nintud…Holy Inanna made a lament for its people. Enki took counsel with himself. An, Enlil, Enki, and Ninhursag made all the gods of heaven and earth take an oath invoking An and Enlil. In those days, Ziudsura the king, the gudug priest…He fashioned…The humble, committed, reverent…Day by day, standing constantly at…Something that was not a dream appeared, conversation…taking an oath by invoking heaven and earth. In the Ki-ur, the gods…a wall.

Ziudsura, standing at its side, heard: “Side-wall standing at my left side, …Side-wall, I will speak words to you; take heed of my words, pay attention to my instructions. A flood will sweep over the…in all the…A decision that the seed of mankind is to be destroyed has been made. The verdict, the word of the divine assembly, cannot be revoked. The order announced by An and Enlil cannot be overturned. Their kingship, their term has been cut off; their heart should be rested about this…[Here there are approximately 38 lines missing]

All the windstorms and gales rose together and the flood swept over the [land]. After the flood had swept over the land, and waves and windstorms had rocked the huge boat for seven days and seven nights, Utu the sun-god came out, illuminating heaven and earth. Ziudsura could drill an opening in the huge boat and hero Utu entered the huge boat with his rays. Ziudsura the king prostrated himself before Utu. The king sacrificed oxen and offered innumerable sheep. [Here there are approximately 33 lines missing]

“They have made you swear by heaven and earth…An and Enlil have made you swear by heaven and earth…”

More and more animals disembarked onto the earth. Ziudsura the king prostrated himself before An and Enlil. An and Enlil treated Ziudsura kindly…they granted him life like a god, they brought down to him eternal life. At that time, because of preserving the animals and the seed of mankind, they settled Ziudsura the king in an overseas country, in the land of Dilmun, where the sun rises…[Here there are approximately 39 lines missing]

Conclusion

The Sumerian Flood Story is considered the first written account of the popular myth of a worldwide flood sent by divine agency which appears in almost every culture of the ancient world. The seemingly universal treatment of the same story has suggested to some that there must have once been such an event, which people of different cultures, independently, responded to with the creation of the story.

Modern-day scholars tend to reject this interpretation and, instead, suggest that an early story of a Great Flood and the destruction of humanity resonated with an ancient audience and came to be widely repeated, traveling through trade from one region to another. Each culture adapted the story to their own needs and vision and so the original was altered, to greater or lesser degrees, as it was told – and then written down – in different locales. The original may or may not have been the Sumerian Flood Story but many scholars in the present day, including Stephanie Dalley, believe it was. Dalley writes:

All these flood stories may be explained as deriving from the one Mesopotamian original, used in traveler's tales for over two thousand years, along the great caravan routes of Western Asia: translated, embroidered, and adapted according to local tastes to give a myriad of divergent versions. (7)

The concept of a god's wrath – or the collective displeasure of many gods – causing catastrophic events was understood simply as how the world worked by ancient civilizations around the world. The story of the Great Flood would have served a number of purposes but, primarily, explained the creation of the world as the people knew it while strongly suggesting they pay greater attention to the divine will in their daily lives.

In each version of the flood story mentioned above, the gods – or God – repent of their decision – in the Genesis story, God even places the rainbow in the sky as a promise he will never flood the world again; but, to an ancient audience, this would not have meant that the Divine could not as easily send some equally dire punishment for human transgression of its will at some point in the future whenever it wanted to. The story would have then encouraged people to err on the side of caution in adhering to religious-cultural precepts in order to maintain the goodwill of a deity or deities who could as easily destroy as support them.