The Estado da India (1505-1961) was the name the Portuguese gave to that part of their empire which stretched from India to East Asia. However, in its widest sense, the name includes all Portuguese colonies east of the Cape of Good Hope and so, at its height in the 16th century, the Estado da India stretched from Africa to Japan.

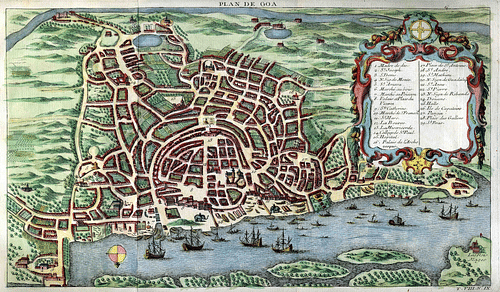

The Estado da India (‘State of India’) was an administrative apparatus established in 1505 to govern the empire and its trade network from its capital at Portuguese Goa in India where the viceroy of the Indies was resident. The Portuguese Empire was largely a string of interconnected ports linked by regular trading fleets. Individual governors took their orders from the viceroy while the Casa da India in Lisbon coordinated all colonial trade and communications. Hugely successful in its maritime and trade objectives in the 16th century, the Estado da India faced intense competition from Muslim and Hindu merchants, local inland rulers, and other European powers from the 17th century. Ultimately, the difficulty in holding on to ports spread across the globe, a preoccupation with Portuguese Brazil, and a chronic lack of manpower and investment, meant that the Estado da India crumbled away, even if some colonies like Portuguese Macao and Goa remained under Portuguese rule into the 20th century.

Establishing the Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese were keen to discover a direct sea route from Europe to Asia which would allow them to bypass the Middle East land and sea trade routes which were controlled by Islamic states. The Portuguese could then have direct access to the highly lucrative Asian spice trade. Additional motivation for forging an empire included the hope that there might be Christian states in South Asia that could become useful allies in Christianity’s ongoing battles with the Islamic caliphates. It was also hoped new resources of precious goods like gold and new agricultural lands could be found. Finally, the Portuguese Crown could win prestige in Europe, and its nobles glory, titles, and riches.

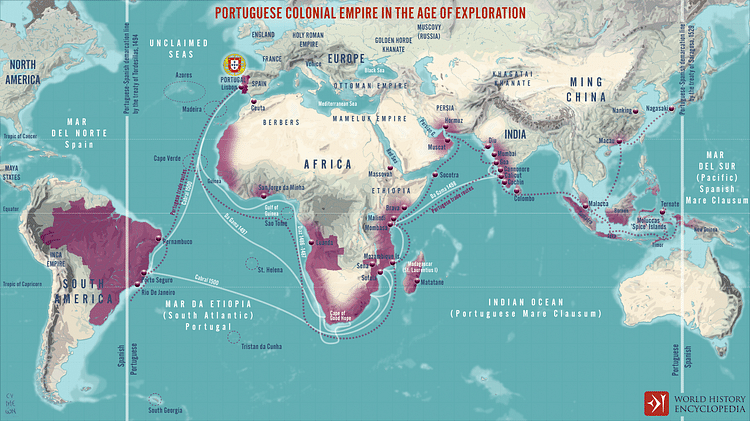

The first step in building an empire was the colonization of three uninhabited archipelagoes: Madeira (1420), the Azores (1439), and Cape Verde (1462) in the Atlantic off the coast of West Africa. The islands of São Tomé and Principe in the Gulf of Guinea were colonised from 1486. The Atlantic islands then acted as stepping stones in a series of maritime explorations that sought to sail down the coast of Africa and reach Asia by sea. In 1497-1499 Vasco da Gama (c. 1469-1524) sailed around the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa, up the coast of East Africa, and crossed the Indian Ocean to arrive at Calicut (now Kozhikode) on the Malabar Coast of south-west India.

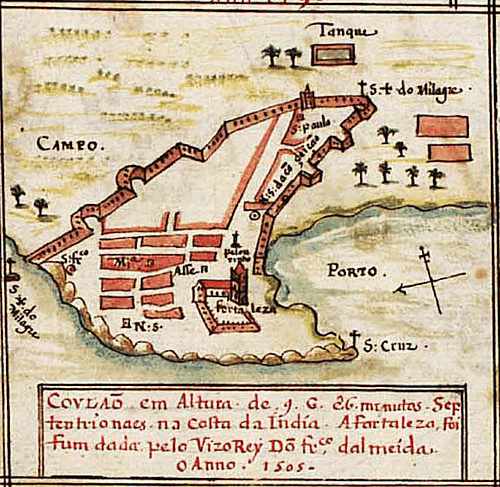

Portuguese Cochin (now Kochi) was established in 1503 on the west coast of India. In 1505, King Manuel I of Portugal (r. 1495-1521), was convinced enough of Portuguese control of the Indian Ocean to appoint the first Viceroy of India, one Francisco d’Almeida. The same year the Estado da India was officially formed. The term did not appear regularly in Portuguese official documents, though, until the mid-16th century. Strictly speaking, the term Estado da India referred to all the official possessions of the Portuguese Crown such as ports, fortresses, and lands in East Africa and Asia. This formal list of possessions was given in a deed of transfer to each new viceroy when they took office. In addition, there were also many unofficial possessions, some of which did at some point become official Crown properties. The majority of these possessions were not territories as such, but single ports with small attached urban areas. This was because the reason for their existence was to control regional trade and provide a safe haven for shipping that criss-crossed the empire.

The Portuguese were not interested in colonising territory or peoples for their own sake, an ambition that later imperial powers certainly did have. Two significant consequences of this policy were that, firstly, most Portuguese colonies did not have enough agricultural land to feed the population and so they were reliant on imports. Secondly, there was no buffer zone protecting the colony from local inland rulers always eager to gain (and in many cases, regain) control of them. Put simply, the Portuguese were in perpetual danger of being pushed back into the sea from where they came. Consequently, the Estado da India was very much a string of perpetually volatile military frontiers linked by fleets like the carreira da India, which made regular round trips from Lisbon to Goa.

The starting point for the Eastern empire was Cochin, which became the administrative capital of the Estado da India. In 1509, colonization gathered apace under the new viceroy, Afonso de Albuquerque (c. 1453-1515). Portuguese Goa was established by Albuquerque in 1510, and within 20 years it replaced Cochin as capital of the Estado da India.

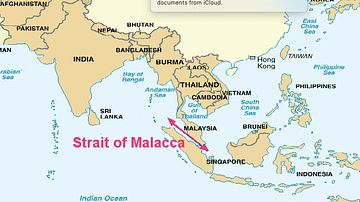

The Portuguese had used a mix of diplomacy and cannons to establish these colonies and muscle in on the Asian trade network. They established a fully-armed naval force, which permanently patrolled the Indian Ocean, and forts were built to protect the colonies in India. Moving eastwards, Malacca in Malaysia was taken over in 1511. To the north, Hormuz at the mouth of the Persian Gulf was colonized in 1515, and a huge fortress was built by Albuquerque (using local forced labour) that ensured Portugal controlled this vital strait for over a century. An attack on Aden, which linked the Indian Ocean to the Red Sea, was unsuccessful, but a Portuguese fort was established at Colombo, Sri Lanka in 1518, at Kollam in 1519 and Chaul in 1521 (both in India). Portuguese Mozambique was given a formidable fortress on Mozambique Island from 1546 as Portugal sought to control the seas enclosed on three sides by Africa, Arabia, and India.

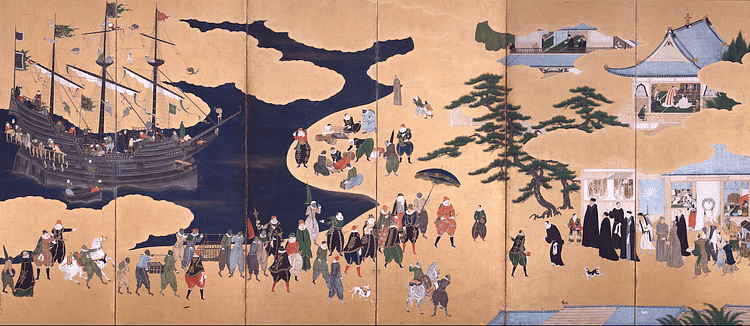

The rise of the Ottoman Empire, which took over from the Mamluks in Egypt and Syria in 1516, resulted in Portugal abandoning any ambitions in Arabia and to, instead, look east for further colonial gains. The next phase of Portuguese expansion relied on finding a sea route from Europe to Asia not by sailing around Africa but sailing west. Christopher Columbus had tried this and found the Americas blocking his way. Ferdinand Magellan (c. 1480-1521), instead, sailed south and round the southern tip of the American continent to reach the Pacific Ocean. From there, his expedition sailed to Indonesia, round the Cape of Good Hope, and back to Europe. This voyage of 1519-1522, was the first circumnavigation of the globe. The empire kept on expanding with Macao in southern China established from c. 1557 and Portuguese Nagasaki from 1571. Every corner of Eastern trade was being brought into the empire, which although not grand in terms of territory, was hugely impressive in terms of the string of coastal trading pearls it had strung for itself across half the globe. Carrack cargo ships traversed the oceans carrying spices, gold, silver, gems, silk, and Ming porcelain.

Colonial Government

The apparatus of colonial government was created for the primary goal of controlling commerce. The Portuguese viceroy, effectively the civil and military governor of Portuguese India, was, in theory, accountable only to the Portuguese king. In Lisbon, the conselho ultramarino advised the monarch on the affairs of the overseas colonies while the Casa da India was the crown agency that supervised all communications and trade with Asia.

The viceroy of the Estado da India resided at Goa, and he created an air of magisterial mystique with his crimson robes, baton of office, and habit of moving around with a vast entourage surrounding his person, which was always shaded by a brocade parasol. The viceroy was assisted by a ruling council, but in the first half of the 16th century, this was an informal body called whenever the viceroy needed specific advice, and its membership varied depending on the expertise required. Only from 1604 would a formal Council of State be formed at Goa. Each Portuguese colony had its own local council, a câmara, which was elected by the Portuguese and Eurasian citizens of the European settlement. The câmara could decide on local government issues, raise local taxes, and act as a first court. Nevertheless, officials in all parts of the empire from East Africa to Japan ultimately took their orders from the viceroy. In the 17th century, Goa, along with a handful of other colonies, was permitted to send representatives to sit in the Portuguese parliament, the Cortes. A posting to the Estado da India was more prestigious than anywhere else until the mid-17th century and the development of Portuguese Brazil.

In the colonies, legal matters were the responsibility of a High Court with Portuguese as the official language. European-style laws were typically only applied to the European or mixed-race populations. Except for Goa and Bassein in northern India, the Portuguese Empire did not involve significant tracts of land where indigenous populations were controlled. In most cases, any local populations within the Portuguese settlement itself were left subject to their own traditional political and legal devices. Only a few colonies like Goa and Malacca had their own mints. The permanent military force of individual colonies, which ensured continued Portuguese rule of the port areas, was led by an appointed captain, who resided in the colony’s fortress. A factor was responsible for royal trade and extracting the lucrative customs duties from other types of trade.

Finally, as capital of the Estado da India, Goa contained an archive of official documents. This archive has provided historians with an invaluable insight into the details of the empire. For example, the Livros das Pazes e Tratados da India is a collection of five manuscript books, which records treaties agreed between Goa and rulers in East Africa, India, Asia, and even European states. The books cover the period from 1571 to 1856. Another work of 25 volumes records all official correspondence between Portuguese colonies and neighbouring rulers in India from 1619 to 1842.

Trade Monopoly

The Portuguese made tremendous efforts to establish a monopoly both of trade between Asia and Europe and within Asia itself. The Crown issued all kinds of decrees that resulted in any private trader - European or otherwise - caught with a cargo of spices and not holding a license or a Portuguese passport (cartaz) being arrested. Their ship and cargo were impounded; many Muslim traders were simply executed. Customs duties were imposed at Portuguese ports and to limit illegal trade, ships were often obliged to travel in Portuguese-controlled convoys (cafilas) and only to sail to selected Portuguese ports. Consequently, customs duties made up around 60% of the entire Portuguese revenue in the East.

The trade across the Indian Ocean was undoubtedly destabilised by these tactics, but it was really only the Portuguese who believed the seas were no longer free. Trade went on regardless between other states, merchants avoided Portuguese-controlled areas, and the vast networks of local trade using small vessels could never be even partially controlled. In addition, the Portuguese eventually realised that a monopoly was detrimental to profits, especially in the form of duties, and so the Estado da India gradually became more accommodating to non-Portuguese trade.

Christianity

Religious affairs in each colony were led by a bishop or archbishop. The archdiocese of the Estado da India was created by a papal bull of 1533 and was headed by the archbishop at Goa. Eventually, archdioceses were created at Cochin, Malacca, Macao, Nagasaki, Cranganore, Meliapore, Beijing and Nanjing, and Mozambique. The Franciscans, Dominicans, Jesuits, Augustinians, and other orders set up monasteries and nunneries everywhere. Europeans of mixed-race and local people did become members of these orders, but very few travelled beyond their own country except for the purposes of instruction in Portugal.

Christian missionaries and organizations, particularly the Jesuits and the Misericórdia brotherhood, built churches, tried to convert local peoples, and dispensed charity, often running educational institutions and hospitals. These missionaries, beginning in 1549 with the Spaniard Jesuit Francis Xavier (aka Francisco de Javier, l. 1505-1552), had varying degrees of success. Members of the church or Christian orders were often used by the Portuguese government in embassies of first contact with foreign rulers from Persia to Japan. Such religious movements as the Inquisition found their way to the colonies and were just as ruthless, unpopular, and socially damaging as they were in Europe. Toleration of local religions varied over time and place, sometimes local peoples were left to their own conscience and permitted to practice their faith, at other times, temples were destroyed and their lands confiscated, cultural practices were restricted or banned such as Hindu marriages, and members of religious communities were ruthlessly persecuted.

Colonial Society

In the colonies, Europeans had the highest status and social display was commonly achieved through fine residences, extravagant clothing, and the number of servants and armed men one had. The higher-ranking officials were almost always members of the nobility of Portugal and usually had military experience. For magistrates in the colonies, an education at the University of Coimbra, where they gained a degree in canon or civil law, seems to have been a prerequisite. The administrators, magistrates, military engineers, doctors, and soldiers could expect a life of mobility as they were posted to various outposts throughout their careers. Below these in status but no less important to the functioning of the colonies was another constantly moving body of skilled craftworkers (the mesteirais) such as stonemasons, blacksmiths, tile-makers, and carpenters. Those with the skills to design and build ships, fortifications, and cannons were in particular demand. Portuguese settlers in the colonies were known as casados.

The colonial Europeans typically divided themselves into three classes: Europeans born in Portugal (a reinol), Europeans born in the colonies (a castiço), and mixed-race Europeans (a descendente or mestiço). On top of this were another four layers based on membership of the nobility (upper level: a fidalguia, lower level: a fidalgo), clergy, army, and all others (subdivided into the married and unmarried). There were also visiting Europeans such as maritime traders, African/Asian traders, and farmers. Then there were the undesirables, the degredados, who were all the people the Portuguese government did not particularly want to keep in Portugal. This group consisted of New Christians (converted Jews and their descendants), Jews, gypsies, convicts, and lepers. If they had no other skills, these people found employment as labourers in the colonies. In all of these groups, Portuguese women were very few indeed, a situation that led to intermarriages with local peoples almost everywhere. The local people in any colony, whether they be Hindu merchants and farmers in Goa or Buddhist Malays in Malacca, made up at least 95% of the total population. At the very bottom of this layer-cake of humanity were the slaves, either bought locally or imported from other parts of Asia or shipped in from colonies like Mozambique and Sāo Tomé.

European Rivals & Decline

The Portuguese struggled to police their vast empire, and many forts suffered from a lack of upkeep, making them relatively easy targets. The Portuguese Crown was overspending back home, and corruption was rife in the colonies. The Dutch arrived in Southeast Asia in 1596 and steadily took over many Portuguese trading centres such as Malacca (1641), Colombo (1656), and Cochin (1663). Goa was attacked repeatedly and besieged but held out. There was a costly war with Spain from 1640 until 1668, and resources had to be diverted to protect Portuguese Brazil from the Dutch attacks there. Defeated in South America, the Dutch turned their attention back to the East. There were, too, localised attacks such as by the Hindu Marathas on Goa in the 17th century. In 1622, the Persians, with English assistance, took over Hormuz.

The British arrived in greater numbers from the mid-17th century, and both Britain and the Netherlands had by then already created highly efficient trading companies: the Dutch East India Company and the British East India Company. They established themselves and turned certain ports into major players in the now-global trade network, powerhouse cities such as Madras (Chennai) and Bombay (Mumbai) in India, Jakarta in Indonesia, Singapore in Malaysia, and Hong Kong in China. The French and the United States joined in as Western colonization moved away from establishing trade monopolies to a much deeper and territorial form of imperialism, a form the Portuguese themselves adopted as shipping losses became more significant. An example of this policy is the acquisition of what became known as the New Conquests around Goa in the mid-18th century. Faced with enemies on all sides, the Estado da India adopted a policy of neutrality, with varying degrees of success, towards all Western powers in Asia.

While much of the dilapidated Portuguese Empire had fallen away like a collapsing house of cards, some colonies did persist, largely thanks to the empire now becoming more manageable in scope and the late-18th-century boom in demand for Asian goods in Europe. The final withdrawal came as the process of decolonization gathered pace after the Second World War (1939-45). Goa was conceded to India after an invasion in 1961 and so the last serving viceroy retired. Macao remained under Portuguese rule until the handover to China in 1999. The Portuguese may have often left their colonies suffering from a chronic lack of care and investment, but their cultural legacy goes on today with the continued use of the Portuguese language, the presence of well-preserved colonial architecture, and the continued importance of Catholicism in many outposts across what was the Estado da India.