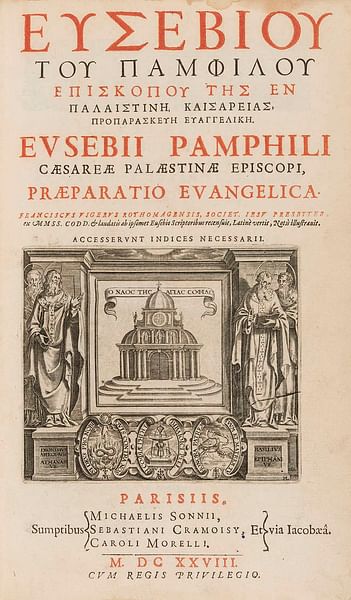

Eusebius Pamphili (aka Eusebius of Caesarea, 260-340 CE) was a Christian historian, exegete, and polemicist. He became the bishop of Caesarea Maritima in 314 CE and served as court bishop during the reign of Constantine I (r. 306-337 CE). Eusebius is known as "the father of Christian history" for his works: Preparation for the Gospel, On Discrepancies Between the Gospels, Ecclesiastical History, and Life of Constantine.

The works of Eusebius provide much of our information on early Christianity in the 4th century CE, although not without debate over his sources and details. The focus of his histories was the Eastern Roman Empire, with only sporadic details included on the West. The name 'Pamphili' is most likely in recognition of one of his teachers, Pamphili of Caesarea.

The Arian Controversy & the First Council of Nicaea (325 CE)

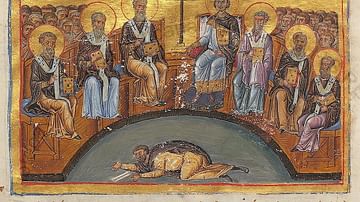

Constantine's conversion to Christianity simultaneously made him the head of the Christian Church in 312 CE. Although he promoted the unity of belief throughout the Roman Empire, a controversy emerged in the city of Alexandria that spilled over into riots in other cities (318-321 CE). Arius, a presbyter in Alexandria, taught that if one believed that God created everything, then at one time, he must have created Christ. The bishop of Alexandria excommunicated Arius, who sought refuge in Caesarea Maritima with Eusebius.

Originally known as Strabo’s Tower, Herod the Great (c. 75-4 BCE) renovated the city of Caesarea and constructed a harbor around 20 BCE. It was an important commercial center during the late Roman Republic and served as the capital of the province of Judea. In the Acts of the Apostles, Luke claimed that it was here that Peter baptized the household of Cornelius the centurion, and where Philip the deacon opened his house to Paul in his missions among the Gentiles (non-Jews). Either because of its importance in trade or because of the traditions of an early Christian community, Caesarea Maritima became an important center for various schools of Christianity, known as catechism schools. A famous teacher in the city was Origen (180-254 CE), who wrote many treatises and commentaries on the New Testament, and Eusebius collected more than 30,00 manuscripts, which positioned Caesarea Maritima as a center of study. When Arius arrived, Eusebius was sympathetic, as Origen had also taught a concept that Christ was subordinate to God.

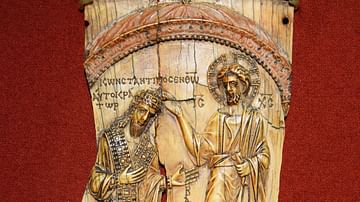

In 325 CE, Constantine called for an empire-wide council in the city of Nicaea to resolve the matter. Arius was brought in chains, and Eusebius defended him. The challenge for the council was to articulate the way in which the oneness of God was also found in his transcendence (through the power of the Spirit) and his incarnate nature (taking on flesh in the Son). The result was the Nicene Creed, which articulated the claim that God and Christ were identical in essence and that Christ was a manifestation of God on earth. It remains debatable how much influence Eusebius had on the various details of the creed. Nevertheless, he refused to sign it and (along with Arius) was sent into exile. However, Constantine later recalled him to serve as bishop at the court in Constantinople, and it was Eusebius who baptized Constantine on his deathbed.

Another Christian historian, Salamanes Hermias Sozomenos (400-450 CE) claimed that Constantine let Eusebius get away with his view because of his services at the imperial court. According to Sozomen, while Constantine was alive, no one had dared to reject the dictates of the Council of Nicaea openly. Upon his death, however, the debate continued in several cities, and Eusebius and Theoginis, a bishop in Bithynia, "did everything in their power to give predominance to the tenets of Arius" (Ecclesiastical History of Sozomen, III.1.)

Since he was trusted, he boldly seized the opportunities, until he became an intimate of the emperor's wife, and of the powerful eunuchs of the women's sleeping apartments. At this period Eusebius was appointed to superintend the concerns of the royal household, and being zealously attached to Arianism, he induced the empress and many of the persons belonging to the court to adopt the same sentiments. Hence disputations concerning doctrines again became prevalent, both in private and in public, and revilings and animosities were renewed. (Ecclesiastical History of Sozomen, III.1.).

The exact date of Eusebius' death is unknown, but Sozomen placed it just before the death of Constantine’s son, Constantine II in 341 CE. In a Syrian martyrology written in 411 CE, Eusebius was listed as a saint, with a festival date of May 30. Armenian church iconography portrayed him with a halo.

The Apology for Origen

Eusebius claimed that much of this work was first written in prison by his teacher Pamphilus with Eusebius’ assistance. In his defense of Origen, Eusebius followed Origen’s concept of God as the creator of all beings and all things good. Origen had claimed that when God created souls, he had created them with free will. Originally created to simply glorify God, these souls utilized their free will to turn away. When they did so, they began to fall away from the source of life. God, in his mercy, then created the material universe to house the souls in their various journeys. Some became stars, some angels, and some humans. One soul, Christ, did not turn away. But God then sent him into the world to enlighten the souls and show them the way home.

For Eusebius, this free will engendered in humans through their soul is what led to their choice to sin and not because they were inherently evil. Hence, punishment for sins is well-deserved, as a righteous judgment for turning against the natural law of God. This idea went against other Christian teachers who claimed that the body was the source of sin (found in its passions and urges). For Eusebius, sin was an intellectual choice.

Ecclesiastical History

Begun c. 290 CE, Eusebius wrote the history of Christianity from the apostolic age to his own time. The work was chronologically coordinated with the reign of the Roman emperors. He provided details on the early bishops and teachers, the successions of bishops in the principal sees, the history of heresies, the history of the Jews, relations with non-Jews (pagans), and the martyrdom of early Christians. His details and quotations from other works (now lost) provide valuable insight into the relationship between the church and state in Late Antiquity.

Life of Constantine

Not a standard biography, Eusebius' Life of Constantine is more of a panegyric (a public speech or publication in praise of someone or something), or perhaps a eulogy after Constantine’s death. One of the most famous passages related the historic conversion of Constantine.

The Emperor had told Eusebius that sometime between the death of his father Constantius in 306 CE and the Battle at the Milvian Bridge in Rome against Maxentius in 312 CE, he experienced a vision, along with his soldiers, of "a cross-shaped trophy formed from light" above the sun at midday. Along with the symbol were the words "in hoc signo vinces" ("in this sign, conquer"). That night in a dream, "the Christ of God appeared to him with the sign which had appeared in the sky, and to use this as a protection against the attacks of the enemy" (Life of Constantine, I.29.).

Another version of this story is related by Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius(250-325), a Christian philosopher who advised Constantine and served as a tutor to his son Crispus. He wrote the Divine Institutes, an apologetic in response to non-Christian critics to demonstrate the reasonableness and truth of Christianity. In 313 CE, Lactantius wrote that Constantine told him that his dream took place on the night before the Battle at the Milvian Bridge. He did not relate the "symbol in the sky" but claimed that Constantine had the symbol of "chi-rho" painted on the soldiers’ shields. "Chi-rho" were the first two Greek letters of Christ, imposed as one over the other. This symbol became known as the staurogram (Greek for "cross") and later became a symbol for the Papacy in Rome.

The two stories remain the subject of debate because of the different details. Eusebius does not place it at the Milvian Bridge, and Lactantius does not have the symbol in the sky. Both agree on Constantine’s dream and his commissioning by Christ himself. Eusebius edited the Life several times so that we cannot determine the date when his version was added, but he did not include this event in his Ecclesiastical History. What remains problematic is the triumphal Arch of Constantine, built by order of the Roman Senate in 315 CE to commemorate his victory over Maxentius. Like many of the monuments in Rome, it was constructed by removing parts of older monuments. In this case, the arch contains elements from earlier monuments to Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius. Therefore, the Arch of Constantine has symbols of Rome’s pagan past to glorify imperial rule, and iconography of Constantine’s conversion to Christianity is not depicted.

Canonization of the Bible

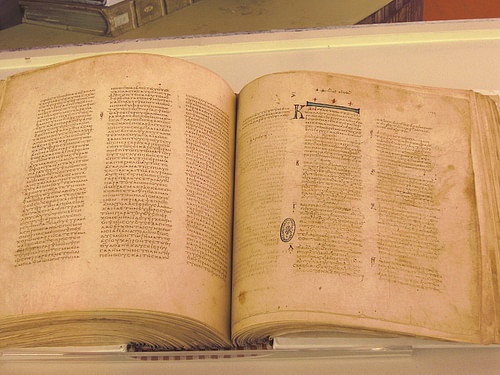

The Life of Constantine is our only source for what became the eventual canonization of the New Testament (along with the inclusion of the Jewish Scriptures). This involves the question of which type of Christianity Constantine converted to. For 300 years there was no central authority that designated universal concepts and rituals. It appears that Constantine followed the teachings of the 2nd-century CE Church Fathers, Christian leaders who wrote what became Christian dogma. These writers argued that the gospels of Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John were the only orthodox (correct) ones, among the many others available at the time, which were deemed heretical writings. According to Eusebius, Constantine wrote to him:

I have thought it expedient to instruct your Prudence to order fifty copies of the sacred Scriptures, the provision and use of which you know to be most needful for the instruction of the Church, to be written on prepared parchment in a legible manner, and in a convenient, portable form, by professional transcribers thoroughly practiced in their art. Such were the emperor's commands, which were followed by the immediate execution of the work itself, which we sent him in magnificent and elaborately bound volumes of a threefold and fourfold form. (Life of Constantine, IV.36-37.)

In Ecclesiastical History, Eusebius discussed the arguments of the Church Fathers for their selection of orthodox gospels. He followed their dismissal of the contradictions found in the four as variations on the direct witness to events as well as interpretations of each evangelist. These details are also found in a separate treatise, On the Differences of the Gospels. There is a long passage on the gospel of John, countering opinions that John was so different from the other three. Eusebius argued that John did follow these sources but that John included later spiritual insight on the true understanding of Christ.

Scholars debate the later manuscripts known as the Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus as to whether they contain Constantine’s original Bible. They differ in the number of folios. Sinaiticus references Eusebius’ canon, but Vaticanus references an earlier version. Eusebius’ accepted writings for the New Testament listed 22 books at the time. The final canonization after years of debate has 27.

Other Works

Eusebius wrote several additional works, some of which have been lost or only survive in later manuscripts that utilized his books. Among these are a separate collection of stories of the early martyrs, Polycarp of Smyrna, Pionius, the martyrs of Vienne and Lyon, and the martyrs of Palestine, written in 311 CE concerning Diocletian’s persecution.

Like all the early Church Fathers, Eusebius, trained in philosophy, utilized the concepts and jargon of the philosophical schools, to claim Christianity’s place in those concepts of the universe. He often cited Plato, and scholars place his Preparation for the Gospel in what is known as Middle Platonism. Plato’s concept of the logos ("rationality" or "word") was found in the earlier preface of John’s fourth gospel. Philosophers had proposed the existence of a higher god behind the gradients of divinities and powers. Eusebius claimed that the God of Israel was this higher god whose divine plan was for the ultimate goal of Christianity from the beginning. Many of the philosophical concepts were repeated in another treatise, On Divine Manifestation, where de defended Christ as the divine logos.

Perhaps as extensions of Preparation for the Gospel, Eusebius went into great detail on the person of Jesus Christ in his Proof of the Gospel. Despite the passage of time and no kingdom of God being established on earth, Eusebius supported the doctrine of eschatological hope, or the return of Christ to usher in the kingdom. Like other Christians, he declared the Jews the enemies of Christ, who would ultimately be subjected by Christians, and their ancient religion would be destroyed.

Another work, Prophetic Extracts, outlined the messianic texts of the books of the Prophets, pointing to Christ. Eusebius also wrote commentaries on the book of Psalms and the book of Isaiah. These have survived through quotations by later Byzantine Christians. He also had commentaries on Paul’s letter to the Romans and 1 Corinthians. Commentaries that have been lost include Judea, a description of the loss of the ten of the twelve tribes of Israel, and A Plan of Jerusalem and the Temple of Solomon. Two of his sermons have survived: one on the consecration of the church in Tyre, and another on the 13th anniversary of Constantine’s reign.

The Legacy of Eusebius

Beginning in Late Antiquity, Eusebius has often been criticized by other historians. Socrates Scholasticus (a 5th-century CE Christian historian), dismissed Eusebius’ Life of Constantine as focused solely on praising the Emperor and not the facts (Church History, I.1.). His methodology and selection of material continues to be criticized due to statements such as the following:

Wherefore we have decided to relate nothing concerning them [some events and persons] except the things in which we can vindicate the Divine judgment. ...We shall introduce into this history in general only those events which may be useful first to ourselves and afterwards to posterity. (Ecclesiastical History, VIII.2.)

In chapter 12, he writes:

I think it best to pass by all the other events which occurred in the meantime: such as ... the lust of power on the part of many, the disorderly and unlawful ordinations, and the schisms among the confessors themselves; also the novelties which were zealously devised against the remnants of the Church by the new and factious members, who added innovation after innovation and forced them in unsparingly among the calamities of the persecution, heaping misfortune upon misfortune. I judge it more suitable to shun and avoid the account of these things, as I said at the beginning.

In other words, Eusebius has already decided against (and judged) all views which did not agree with him in the narration of events. And then there is this in Preparation for the Gospel:

It will be necessary sometimes to use falsehood [fiction] as a remedy for the benefit of those who require such a mode of treatment (XII.31.).

However, to judge such statements through the lens of modern historiography – which we claim is objective – is to ignore the way in which all ancient historians wrote their narratives. In their telling of what happened, they also included the meaning of these events, their interpretations as well as polemical judgment evaluations of the characters. Despite criticism, the consensus agrees that without the writings of Eusebius, we would have little access to events and people in the formative years of Christianity. His information is invaluable for classicists, historians of the later Roman Empire, and theologians.