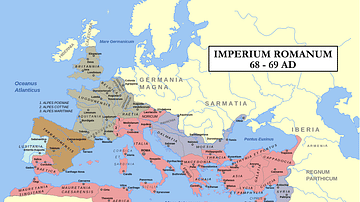

Galba was Roman emperor from June 68 to January 69 CE. With the death of Emperor Nero on June 9, 68 CE, the Julio-Claudian dynasty officially ended, leaving the Roman Empire without a clear successor to the throne. With the assistance of the army, Galba, governor-general of Spain, quickly rose to fill the void.

Early Life

Servius Sulpicius Galba was born into an aristocratic family on December 24, 3 BCE to Gaius Sulpicius Galba and Mummia Achaica. An older brother, Gaius, (ten years his senior) would later commit suicide in 36 CE, due to “financial embarrassment,” after incurring the ire of Emperor Tiberius. While little in known of Galba's early years, historian Suetonius in his The Twelve Caesars wrote that Emperor Augustus singled Galba out of a group of young boys and said, “You too will taste a little of my glory, child,” suggesting that Galba would one day be emperor. The news did not seem to impact Tiberius, the eventual successor to Augustus, when he replied, “Very well, let him live in peace; the news does not concern me in the least.” Suetonius added that the future emperor was “a conscientious student of public affairs, and particularly skilled in law…”

As for his appearance, he was completely bald (although coins of the era picture him with hair) and suffered a severe case of arthritis, crippling both his hands and feet – he was even unable to wear shoes. Galba's only marriage (considered little more than a formality – since he was thought to be homosexual) was to Semilia Lepides. After her death and those of his children, he refused to remarry, despite pressure to do so.

With the exception of Nero, the other Julio-Claudians —Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula and Claudius— seemed to respect Galba, enabling him to hold a series of public offices. He rose rapidly through the ranks, eventually becoming governor of Africa (44 – 45 CE). Earlier in 40 CE, Emperor Caligula had appointed him commander of a legion in Upper Germany, something that endeared him to the young emperor but not to his men. Suetonius wrote, “In grueling manueuvres (sic) he toughened old campaigners as well as raw recruits and sharply checked a barbarian raid into Gaul.” Early on, he had earned a reputation for both cruelty and ruthlessness. Galba believed any sign of disobedience or disrespect to be completely unacceptable and, therefore, a challenge to his authority. His reputation and ability to command grew. Upon the death of Caligula, many even suggested that he assume the throne; but he refused — a gesture that earned the respect of Emperor Claudius. For this loyalty, Claudius appointed him pro-consul of Africa with orders to suppress a series of disturbances and native revolts.

Galba abruptly dropped out of public service in 49 AD; supposedly he had rejected the advances of Claudius's wife and Nero's mother, Agrippina the Younger. He eventually returned to service in 60 CE at Nero's request when the governorship of Spain became available. He held the position for eight years, but as the empire began to crumble under the poor leadership of Nero, many of the provincial governors began to call for his ousting. Marcus Salvius Otho, governor of Lusitania, and Gaius Julius Vindex, one of the governors of Gaul, appealed to Galba to overthrow Nero. Suetonius wrote, “…messengers arrived from Rome with the news that Nero, too, was dead, and that the citizens had all sworn obedience to himself (Galba), so he dropped the title of governor-general and assumed that of Caesar.” Galba was also motivated by rumors that Nero had wanted him assassinated.

Galba as Emperor

With the assistance of Otho (who had been exiled to Lusitania by Nero), Galba raised additional legions and marched into Rome, and with the news of Nero's death verified, assumed the throne. According to Cassius Dio in his Roman History, Nero was at a loss when he heard of Galba being declared emperor by his soldiers. He created a plan to kill all the senators, burn Rome, and flee to Alexandria: “He was on the point of putting these measures into effect when the senate withdrew the guard that surrounded him and then, entering the camp, declared him an enemy and chose Galba in his place.”

Suetonius wrote that his assumption of the throne was not entirely popular: “His power and prestige were far greater while he was assuming control of the Empire than afterwards; though affording ample proof of his capacity to rule, he won less praise for his good acts than blame for his mistakes.” Mistakes? Suetonius added, “He sentenced men of all ranks to death without a trial or the scantiest of evidence… but the most virulent hatred of him smouldered in the army.” He demanded tribute from many of the towns he had conquered, keeping the money for himself. He also seized money from many of the people Nero had lavished; however, the recovered money was not spent on his troops — an act that alienated his own men. He no longer felt his hold on the throne was dependent upon them, so why should he bribe them. To the citizens of Rome, who had welcomed the death of Nero, he no longer spent money on lavish shows (i.e. gladiatorial games), considering them a waste of money. Rumors of unrest in many of the provinces, Germany for one, began to emerge.

Death & Successor

Because he was in his early seventies and with his hold on the throne tenuous, Galba adopted Lucius Calpurnius Piso Licinianus as his son and heir, an act that angered his long-time supporter Otho, who had considered himself the rightful successor. With no alternative and the support of the military, Otho bribed the Praetorian Guards (they felt little loyalty of Galba) who murdered both Galba and Piso in the Roman Forum, bringing their severed heads to him. Otho was hailed as the new emperor in January 69 D. Galba had served less than seven months, becoming the first in a line of what would later become known as “the year of the four emperors.”