The Gandhara Civilization existed in what is now Northern Pakistan and Afghanistan from the middle of the 1st millennium BCE to the beginning of the 2nd millennium CE. Although multiple major powers ruled over this area during that time, they all had in common great reverence for Buddhism and the adoption of the Indo Greek artistic tradition which had developed in the region following Alexander's invasions into India.

The Extent of Gandhara

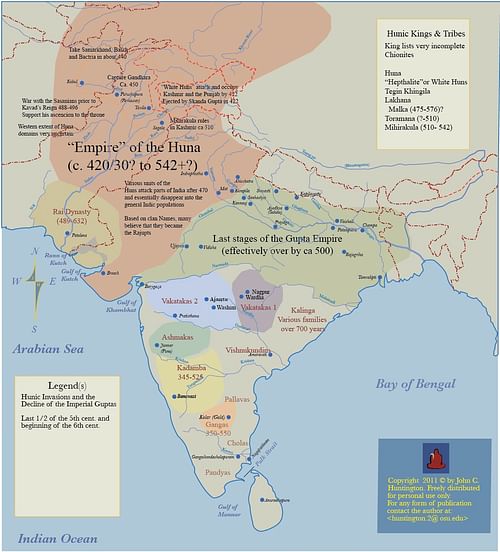

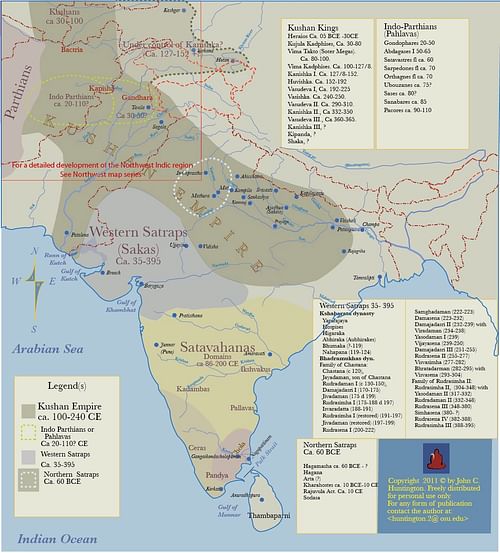

Although mentioned in historical sources at least as far back as the reign of the Achaemenid king Cyrus the Great (r. c. 550-530 BCE), Gandhara was not known to have been geographically described in detail until the pilgrimage of the Buddhist monk Xuanzang (Hsüan-tsang, 602- 664 CE) in the 7th century CE. He visited the region during the tail end of the Gandhara civilization, after the time when it had achieved its greatest feats and was falling into decay. Following ancient Buddhist sources, he described quite accurately the area and its various cities and sites, being the first known account that survives to the modern day and indeed which helped in identifying the remains found in this region during modern times as being of Gandharan origin.

It has been speculated that Gandhara was a triangular tract of land about 100 kilometers east to west and 70 km north to south, lying mainly to the west of the Indus River and bounded on the north by the Hindukush Mountains. The extent of Gandhara proper actually included the Peshawar valley, the hills of Swat, Dir, Buner, and Bajaur, all of which lie within the northern boundaries of Pakistan.

However, the bounds of Greater Gandhara (or regions where the cultural and political hegemony of Gandhara held sway) extended towards the Kabul Valley in Afghanistan and the Potwar plateau in the province of Punjab in Pakistan. Indeed during certain times, the influence spread as far as Sindh where remains of a stupa and Buddhist city are still visible built over the even older remains of Mohenjo-daro. Well-known cities of the Gandhara include Takshasila (Taxila), Purushapura (Peshawar) and Pushkalavati (Mardan), where remains have been discovered and continue to be found to this day.

Origin of the Name Gandhara

The name of Gandhara may have several meanings, but the most prominent theory relates its name to the word Qand/Gand which means "fragrance", and Har which means 'lands'. Hence in its simplest form, Gandhara is the 'Land of Fragrance'.

Another more probable and geographically supported theory is that the word Qand/Gand is evolved from Kun which means 'well' or 'pool of water' and indeed the word Gand appears with many other place names associated with water i.e. Gand-ao or Gand-ab (pool of water) and also Gand-Dheri (water mound). Tashkand (stone-walled pool) and Yarkand are also associated names and hence it holds to reason that the land could have been known as 'Land of the Lake(s)'. This is further supported by the Peshawar vale even today being blessed with good drainage especially during the rainy season, resulting in a lake-like appearance to the marshes which are today covered with crops and fields.

Political History of Gandhara

Gandhara witnessed the rule of several major powers of antiquity as listed here:

- Persian Achaemenid Empire (c. 600-400 BCE)

- Greeks of Macedon (c. 326-324 BCE),

- Mauryan Empire of Northern India (c. 324-185 BCE),

- Indo-Greeks of Bactria (c. 250-190 BCE),

- Scythians of Eastern Europe (c. 2nd century to 1st century BCE),

- Parthian Empire (c. 1st century BCE to 1st century CE),

- Kushans of Central Asia (c. 1st to 5th century CE),

- White Huns of Central Asia (c. 5th century CE)

- Hindu Shahi of Northern India (c. 9th to 10th century CE)

This was followed by Muslim conquests by which time we come to the medieval period of Indian history.

Achaemenids & Alexander

Gandhara was briefly part of the Achaemenid Empire but Achaemenid occupation did not last long. Later on, it was instead known to be a tributary state of the Achaemenids (known as a satrapy) and later paid tributes and inferred hospitality to Alexander the Great who eventually conquered it (along with the rest of the Achaemenid Empire). The Achaemenid hegemony in Gandhara lasted from the 6th century BCE to 327 BCE.

Alexander is said to have crossed through Gandhara to enter into Punjab proper (the same function it serves today) and he was offered alliance by the ruler of Taxila, the Raja Ombhi, against his enemy Raja Porus, who was a constant source of agitation for Taxila and its regions of influence. This culminated in the Battle of Hydaspes, the telling of which is an integral part of Alexander's victories in India. Nonetheless, Alexander's stay here was short, and he eventually ventured south via the Indus River, crossing west over into Gedrosia (Balochistan) and onward into Persia, where he met his demise.

Mauryan Rule

By 316 BCE, King Chandragupta of Magadha (321-297 BCE) moved in and conquered the Indus Valley, thereby annexing Gandhara and naming Taxila a provincial capital of his newly formed Mauryan Empire. Chandragupta was succeeded by his son Bindusara, who was succeeded by his son Ashoka (a former governor of Taxila).

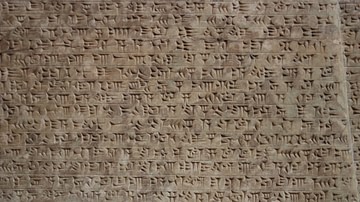

Ashoka famously propagated the spread of Buddhism by building multiple monasteries and spreading the edicts of his “Dharm” across the subcontinent. One of these is the grand Dharmarajika monastery east of the river Tamra at Taxila, famous for its stupa, and it is said Ashoka buried several relics of Buddha there. Mankiyala, Dharmarajika, and Sanchi are said to be contemporary stupas.

Indo-Greeks

In 184 BCE, the Greeks (who had remained strong in Bactria, modern North Afghanistan), invaded Gandhara again under king Demetrius, and it was he who built a new city on the opposite bank of the river from Bhir Mound. This new incarnation of Taxila is known now as Sirkap (meaning 'severed head'), and it was built according to the Hippodamian plan following a gridiron pattern.

The Kingdom of Demetrius consisted of Gandhara, Arachosia (modern-day Kandahar in Afghanistan), the Punjab, and a part of the Ganges Valley. It was a multiethnic society, where Greeks, Indians, Bactrians, and Western Iranians lived together. Evidence of this is found all over 2nd-century BCE Taxila, such as a Zoroastrian sanctuary at Jandial, directly north of Sirkap.

Scytho-Parthians

The gradual takeover of the Punjab by the nomadic Scythians of Central Asia began around 110 BCE. These tribes had been accustomed to invading northern territories such as those in Bactria but had been kept back by the Achaemenids in the past. They had settled in Drangiana, modern-day Sistan in Iran and invaded Punjab, infiltrating through the southern Indus Valley, eventually taking over Taxila.

In the first quarter of the 1st century CE, the Parthians moved in and began taking over the Greek kingdoms in Gandhara and Punjab. Gondophares, a Parthian leader who lived at Taxila is said to have been baptised by the apostle Thomas, not a wholly impossible claim since the city already hosted a number of religious faiths and might have accommodated a fledgling Christian one nearly 2000 years ago.

Kushans

The Kushans were a tribe that migrated to Gandhara around the 1st century CE from Central Asia and Afghanistan. The tribe selected Peshawar as its seat of power and later expanded east into the heartland of India to establish the Kushan Empire, which lasted until the 3rd century CE. In 80 CE, the Kushans wrested control of Gandhara from the Scytho-Parthians. The main city at Taxila was again refounded at another site and the new name Sirsukh given to it. It resembled a large military base, with a wall 5 km long and 6 metres thick. It now became a hub of Buddhist activity and hosted pilgrims from Central Asia and China. The Kushan era is the high point of Gandhara art, architecture, and culture and considered a golden age in the history of this region.

The Greek philosopher Apollonius of Tyana also visited the city of Taxila and compared its size to that of Nineveh in Assyria. A description of Taxila (probably Sirsukh) can be found in the Life of Apollonius of Tyana by the author Philostratus:

I have already described the way in which the city is walled, but they say that it was divided up into narrow streets in the same irregular manner as in Athens, and that the houses were built in such a way that if you look at them from outside they had only one storey, while if you went into one of them, you at once found subterranean chambers extending as far below the level of the earth as did the chambers above. (Philostratus, Life of Apollonius, 2.23; tr. F.C. Conybeare)

The tail end of the Kushan rule saw a succession of short-lived dynasties taking over control of the Gandhara region, and this resulted in a situation where the region was constantly being raided, invaded or in some way or other in turmoil. A quick succession of rule by the Sassanian Empire, Kidarites (or little Kushans), and finally the White Huns following the ebbing of Kushan rule led to day to day religious, trade, and social activity coming to a standstill. In about 241 CE, the rulers of the area were defeated by the Sassanians of Persia under the kingship of Shapur I and Gandhara became annexed to the Persian Empire. However, under pressure from the northwest, the Sassanians could not directly rule the region and it fell to descendants of the Kushans, who came to be known as the Kidarites or Kidar Kushans which literally means little Kushans.

White Huns

The Kidarites managed to hold the region, carrying on the traditions of their Kushan predecessors up to the middle of the 5th century CE when the White Huns, or Hephthalites, invaded the region. As Buddhism and by extension Gandhara culture was already at an ebb by this time, the invasion caused physical destruction, and due to the Huns' adoption of the Shivite faith, the importance of Buddhism began to wane with even more speed.

During the White Hun invasions, the religious character of the region shifted gradually towards Hinduism and Buddhism was shunned in its favor, as it was deemed politically expedient by the White Hun who sought to make alliances with the Hindu Gupta Empire against the Sassanids. The change in religious character (which was the basis of all social life for centuries) led to a further decline in the character of the Gandhara region.

The White Huns' alliance with the Gupta Empire against the Sassanians also caused the culture of Buddhism to be subdued to the extent that eventually the religion moved up through the northern passes into China and beyond. Hinduism then took sway over the region and the Buddhist people moved away from here. The remaining few centuries saw constant invasions from the west, especially Muslim conquest, due to which the few existing remnants of the older culture eventually fell into obscurity. The old cities and worship places of importance hence fell out of memory for the next 1500 years until they were rediscovered in the mid 1800s CE by colonial British explorers.

Gandhara had various rulers over the centuries but archaeological evidence shows us that the uniformity of its cultural tradition persisted during these changes in rule. Although the territories were spread over vast areas, the cultural boundaries of regions such as Mathura and Gandhara were well defined and can be identified through countless archaeological remains.

Gandharan Art

Gandharan art can be traced to the 1st century BCE and included painting, sculpture, coins, pottery, and all the associated elements of an artistic tradition. It really took flight during the Kushan era and especially under King Kanishka in the 1st century CE, who deified the Buddha and arguably introduced the Buddha image for the first time. Thousands of these images were produced and were scattered across every nook and cranny of the region ranging from handheld Buddhas to monumental statues at sacred sites of worship.

Indeed it was during Kanishka's time that Buddhism saw its second revival after Ashoka. The life story of the Buddha became the staple subject matter for all aspects of Gandharan art, and the sheer number of Buddha images enshrined in chapels, stupas, and monasteries continue to be found in great numbers to this day. The artwork was solely dedicated to the propagation of religious ideals to the extent that even items of everyday use were replete with religious imagery.

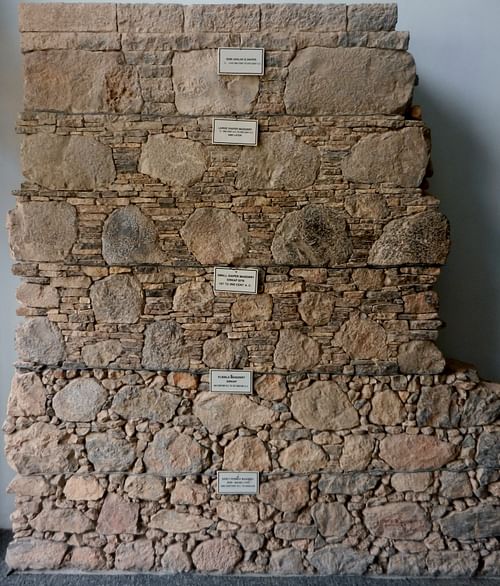

The materials used were either kanjur stone finished with plaster and paint or Schist stone. Kanjur is basically fossilized rock which can be easily molded into shapes which are used as a base for various decorative elements in Gandharan art such as pilasters, Buddha figures, brackets, and other elements. After the basic shape has been cut out of stone, this is then plastered to give it a finished look. Gold leaf and precious gems were also applied to select items. The maximum transportable size the schist stone statues was 2.5 square meters; the larger statues and reliefs are made of clay and stucco.

The Buddha was worshipped through these sculptural representations which had a distinct style associated with them that remained largely constant. The Buddha is always depicted in simple monastic robes, with his hair tied in a bun known as the Ushnisha and the expression on his face is almost always one of content. Whereas originally these sculptures were painted in bright colors, now only the plaster or stone remains; a handful of items have been found with their original colors intact. Images of the Buddha were made for the various cults in the region all of which had their own distinct identifying features such as the laksanas (divine marks), mudras (hand gestures), and different robes. Buddha always had the central role in these pieces and can be immediately identified by the halo and his simple attire. Many mythological figures are also seen as a part of these scenes along with couples, gods, demigods, celestials, princes, queens, male guards, female guards, musicians, royal chaplains, soldiers, and also common people.

One of the most enduring elements of Gandharan art besides the Buddha is the Bodhisattva, which is essentially the state of the Buddha before he attained his enlightenment. Various Bodhisattvas from the previous lives of the Buddha are depicted in Gandharan art, with Avalokiteshvara, Maitreya, Padmapani, and Manjsuri being prominent. Compared to the austerity of the Buddha images, the Bodhisattva sculptures and images depict a high degree of luxury with variations in jewelry, headdress, loincloth, sandals, etc., and so the various incarnations of the Bodhisattva are recognizable from their clothing and postures, and mudras.

Gandharan Architecture

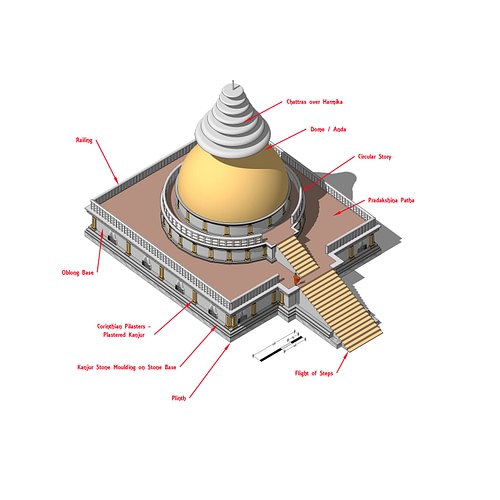

The most prominent and unique characteristic of Gandharan architecture was the proliferation of stupas and other associated religious establishments such as monasteries which formed the core of the regional identity for nearly 1000 years. The stupas were built mainly for the reverence of the remains of Buddhist masters, and the oldest ones were said to hold the remains of the Buddha himself. Besides the Buddha, monks of high stature were also venerated by having stupas built for them, and these edifices also marked locations where certain legendary events related to the various lives of the Buddha were said to have occurred.

Stupas were initially built with circular bases and were of modest size. But as the cult of the Buddha grew in importance in the region, these centers of worship were elaborately redesigned and adorned to boost the stature of the religion and to attract more worshippers and patrons. The original stupas at Kunala and Dharmarajika are known to have been small affairs which were later on expanded to grand proportions by rulers such as Asoka and Kanishka.

A base (medhi), either circular or square, would support a drum or cylinder on top of which the dome (anda) would be placed. Steps were used to surmount the platform and to begin the clockwise circumambulation around the dome along the processional path (Pradakshina Patha) which was bounded by the railing (vedika). At times the base would have multiple circular stories raising the height of the stupa. The corners of the base were usually affixed with lion capital pillars and the top of the dome had first a harmika, an inverted square enclosure on which stood the yasti or pillar which had the various chattras or parasols diminishing sizes equally distributed along it.

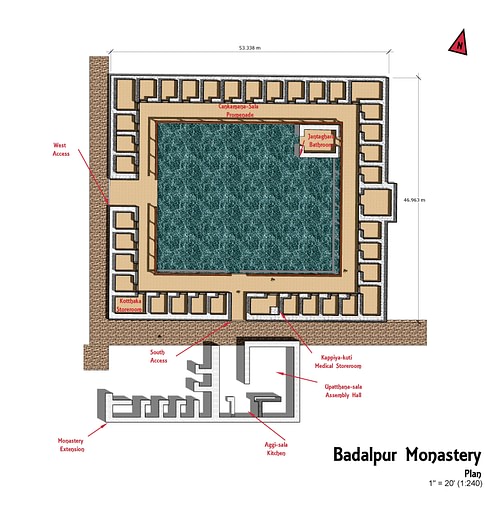

The stupa was the main center of worship, and, in support, it had the monastery, a structure with its own fully contained living area for monks. The monastery or Sangharama became a huge part of the Buddhist tradition and over time came to be its own self-sustaining unit, with lands for growing crops and wealth showered on them by laypeople and royalty alike for their blessings. In its final form, the monastery had some defined elements which suited its basic functions and these were:

- Refectory/Service Hall: Upatthana-sala

- Kitchen: Aggi-sala

- Cloistered Promenade: Chankamana-sala (for walking/exercise)

- Bathroom: Jantaghara next to the central water tank

- Storeroom: Kotthaka

- Medical and general storage: Kappiya-kuti

These buildings were usually rendered in mud plaster and this was then painted over either completely or like in some cases (as in the monastery of Jina Wali Dheri in Taxila) scenes of the Buddha's life.

Aside from these religious buildings, there was, of course, civic architecture which varied and changed with the culture prevalent in the region. Cities ranged from organic settlements such as Bhir to the more rigid and planned settlements like Sirsukh. The older cities developed organically while the newer ones seem to be very directly inspired by the Hippodamian layout which surfaces later in the 1st century BCE. Shops, promenades, palaces, temples, sundials, hovels, huts, villas, insulae, pavilions, streets, roads, watchtowers, gates, and fortification walls, all form part of the urban fabric which is true of most ancient cities as well.

Although the religious landscape was dominated by the Buddhist faith, there is nonetheless ample evidence of other faiths intermingling and thriving in the social fabric such as Jainism, Zoroastrianism, and early Hinduism amongst others. The temple at Jandial is said to be Zoroastrian in nature whereas a Jain temple and a temple of the Sun is in evidence on the main street of Sirkap city along with various stupas.

Conclusion

Daily life in the cities of Gandhara was very well-developed, and due to its favorable location between India, Persia, and China, it constantly saw invaders, traders, pilgrims, monks, and travelers cross through its lands. Westwards from India or eastwards from Persia, the route through the region of Gandhara made it the center of every traveler's route. This is the same route through which Islam entered the region and probably struck the final nail in the coffin of Buddhism in the area. In fact, the same route would be used for centuries even after Gandhara collapsed until the Age of Discovery.

The riches of Gandhara, although well known to treasure hunters for centuries, would not be discovered again until the era of British colonial rule in the Indian subcontinent, when the artistic traditions of this lost civilization were rediscovered and brought to light in the late 19th and throughout the 20th centuries CE.