Ganymede (pronounced GAH-nuh-meed) is a youth in Greek mythology who is abducted by Zeus because of his great beauty and brought to Mount Olympus to serve as cupbearer. The story first appears in Homer’s Iliad without any suggestion of a sexual connection, but Ganymede later became associated with male same-sex relationships and homoerotic passion.

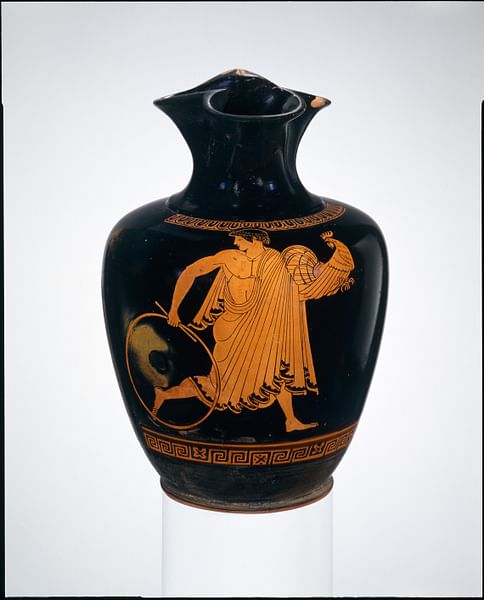

The myth as given by Homer (8th century BCE) simply relates how the gods recognized Ganymede’s beauty and brought him to Olympus to be Zeus’ cupbearer. By the 6th century BCE, however, the story was given as Zeus falling in love with Ganymede and taking him to be his lover. Greek tragedy playwright Sophocles (l. c. 496 - c. 406 BCE) among other 5th-century dramatists and poets, mentions Ganymede and Zeus as lovers and developed the already established romantic-erotic element, which eventually led to the couple becoming the archetype of the same-sex lover-beloved relationship featured on cups, plates, and kraters (wine jugs) in ancient Greece and, later, in Rome.

Ganymede continued as a popular subject in the arts and is associated with the constellation of Aquarius as he is said to have renounced his privileged position as cupbearer to give the waters of the gods to humanity, thereby becoming the water-bearer and benefactor of mortals. At different times in history, he has come to represent different values reflecting those of the majority in any given society, but in the modern day, he is most closely identified with the LGBTQ+ community, which focuses on the love expressed by the couple and Ganymede’s sacrifice of his favored position to benefit others and keep peace among the gods.

The World of the Myth

The Homeric world the myth first appears in was presided over by powerful deities who maintained their own vision and definition of order which might sometimes seem at odds with those of the people. Abducting a young man against his will would have been considered a criminal act in Greek society no matter which city-state it occurred in, but when a god did the same, it was forgiven and understood as happening for a reason. In describing the Homeric world, the scholar Emile Mireaux notes:

The world in effect is a society of living entities, who inhabit earth, sea, and sky and are at the same time indistinguishable from them. Are these creatures of divine origin? The answer is, yes, in a certain measure, but the degree of their divinity is a variable and indeterminate quality, for all are not immortal. Moreover, it is a society organized as a hierarchy very similar to the human groups, similar inasmuch as it is equally disorderly and turbulent; torn by dissentions, passions, jealousy and competition…Man in the Homeric age, at least thinking man, has his being in intimate and constant contact with this divine or semi-divine society. To tread the earth underfoot, to bathe in waters, is tantamount to having this contact…Man has the sentiment or perception of visitations by the gods, even the greatest of them. (24-25)

The Greek myths include many stories of people encountering or being abducted by a deity. The goddess of dawn, Eos, alone, kidnapped a number of men for her pleasure, and, of course, gods could and did also kidnap other gods as in the case of Hades and Persephone. The story of Ganymede as it originally appears in the Iliad is just another such abduction tale:

Tros was lord of the Trojans and to him there were born three sons, unfaulted, Ilus and Assaracus and godlike Ganymede who was the loveliest born of the race of mortals, and therefore the gods caught him away to themselves, to be Zeus’ wine-pourer, for the sake of his beauty, so he might be among the immortals. (20.232)

There is no mention in this passage of Ganymede’s age or Zeus himself having any particular interest in the youth (though this would later change, and, in the period of the Renaissance, Ganymede was sometimes depicted as a child or infant). The gods decide to take him to Olympus because of his great beauty, which they want to preserve by making him immortal. This same theme is kept by later writers but is joined by Zeus’ infatuation with Ganymede and their love affair. Theognis, writing in the 6th century BCE, is an early example:

There is some pleasure in loving a youth, since once in fact even Zeus, the son of Cronos, king of the immortals, fell in love with Ganymede, seized him, carried him off to Olympus, and made him divine, keeping the lovely bloom of boyhood. (Fragment 1.1345)

Homer himself does not present same-sex relationships explicitly but, in the case of couples such as Achilles and Patroclus, provides enough details that the nature of the men’s connection is clear. In the case of Ganymede, however, the abduction of the youth is not associated with any kind of romantic or erotic relationship until later. It is possible, of course, that an ancient audience would have understood Homer’s passage as alluding to a same-sex relationship right from the start, but this is uncertain. By the 6th century BCE, however, that seems to have been the most common understanding of the story.

Myth of Ganymede

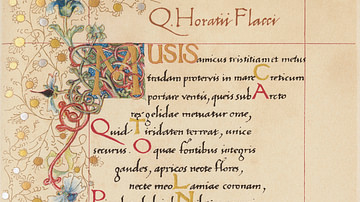

Based upon the number of times and wide array of writers referencing the tale, it must have been quite popular. There is no one set version of the story until it is taken up by the Roman writer Ovid (l. 43 BCE - 17 CE), but each writer between Homer and Ovid seems to be referencing the same story, which differs from Homer’s.

The myth relates the story of Tros, founder of the city of Troy, and his three handsome and flawless sons, of whom Ganymede, the youngest, was the most beautiful. One day, while tending his flocks on Mount Ida, he is seen by Zeus who swoops down in the form of an eagle and snatches him up, carrying him to Olympus. Once there, Ganymede becomes Zeus’ young lover and cupbearer, replacing Hebe, goddess of youth, who had held the honored cupbearer position. Hera, Queen of the Gods, Zeus’ wife, and Hebe’s mother is enraged at the new arrival and, in some later versions, causes him various problems at court. Ganymede, realizing how much trouble she can cause him and everyone else at court, and looking for a way to have Zeus release him, and at the same time, wanting to help the people of earth, pours out the water of the gods for the mortals. Zeus realizes he has treated the young man poorly, as well as the boy’s father, and sets Ganymede in the heavens as the constellation Aquarius while rewarding Tros with divine horses. Ganymede becomes the water-bearer for humanity, Hebe returns to her role as cupbearer for Zeus, and Hera is mollified for the time being until Zeus’ next escapade.

This is the basic form of the tale, but different versions include varying details. In some, Zeus sends a giant eagle to abduct the youth, in others he appears as a man. In some, Ganymede seems as young as 12, in others, he may be around 16. Hera does not always act on her desires to make Ganymede’s life miserable, and Hebe does not always return to her position of cupbearer. All of the versions seem to agree, however, on Zeus’ romantic and sexual relationship with Ganymede. Some sources are critical of the specific relationship, but most regard same-sex relations as perfectly natural in keeping with the ethos of the Homeric world and the acceptance of what, today, would be defined as homosexual relationships in 6th-4th-century BCE Greece.

The Lover & Beloved

During this period, as well as earlier and later, same-sex relationships were regarded as just another expression of romantic and sexual attraction. There was no distinction between a homosexual and heterosexual relationship because those concepts did not exist. Same-sex relationships were part of the cultural landscape but, for the most part, they were not viewed critically. Scholar Anthony Everitt notes:

Men did not categorize themselves as homosexual for, until the inventions of modern psychology, there was no concept, and so no term, for man-to-man sexual preference as a viable and exclusive alternative to heterosexuality. (241)

The most common form of such relationships was between an older lover (erastes) and a younger beloved (eromenos) based on friendship (philia) which also had a sexual component to it. Later writers interpreted the Ganymede story along these lines, with Ganymede as the beloved who is improved upon by the affection and nurture of the older lover Zeus. Not everyone interpreted the story in this same way, however, and some of the best-known writers of ancient Greece either rejected this view of the myth completely or came to later in life.

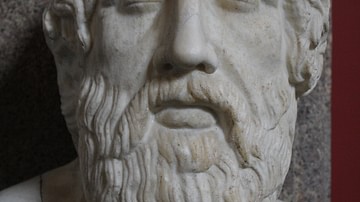

Xenophon (l. 430 - c. 354 BCE), for example, claimed Ganymede was admired by Zeus for his intellectual abilities and there was no physical attraction nor any sexual connotation to the relationship at all. Plato (l. c. 428/427 - 348/347 BCE), who initially recognizes a lover-beloved relationship between the god and the youth in his dialogue of the Phaedrus (255), retreats from this position and reverses himself in his much later dialogue of the Laws where he blames the Cretans for 'inventing' same-sex relationships and justifying the practice through the myth of Ganymede:

One certainly should not fail to observe that when male unites with female for procreation, the pleasure experienced is held to be due to nature, but contrary to nature when male mates with male or female with female, and that those first guilty of such enormities were impelled by their slavery to pleasure. And we all accuse the Cretans of concocting the story about Ganymede because it was the belief that they derived their laws from Zeus so they added on this story about Zeus in order that they might be thought to be following his example in enjoying this pleasure as well. (636c)

There is no more evidence that the Ganymede myth came from Crete than from anywhere else, but Plato’s remarks are interesting as they express an older poet-philosopher’s view of same-sex relationships, particularly that of the lover and beloved, which was widely practiced and which he formerly approved of. Plato’s lines from Laws are frequently cited as 'proof' that same-sex relationships were not universally approved of in ancient Greece, but Plato’s earlier works of Symposium and Phaedrus, as well as many of his others, are supportive of such relationships, even praising them as the foundation of democracy and an elevation of the soul because they were freely chosen and had nothing to do with the value society set on procreation.

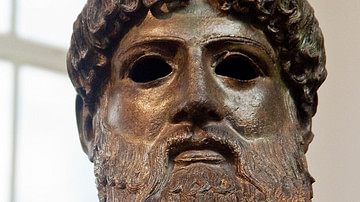

The Ganymede myth was invoked by many, especially through the visual arts, to celebrate homoerotic relationships. The so-called Berlin Painter depicted Ganymede’s story on a red-figure krater (a vessel for mixing wine with water to dilute it) which shows him as an athletic young man enjoying gifts given him by Zeus. Most ancient depictions follow along these same lines, and it is only later, during the medieval and Renaissance periods of Europe, that Ganymede is shown as a child or an infant and the myth is given a derogatory interpretation.

Ganymede as Symbol

As noted, Ganymede became a symbol reflecting the values of a culture at different times, and by the Renaissance period, Christian interpretations of Greek myths prevailed. Passages from the epistles of St. Paul the Apostle which make up the Christian New Testament as well as some from the Old Testament Book of Leviticus were understood as condemning same-sex relationships and so Ganymede was frequently depicted as a child abducted by a god in eagle form to either distance the story from the theme of such relationships or impress upon an audience how perverse such a relationship should be viewed.

The passages from the Bible which are, even now, cited as condemning same-sex relationships, however, all have to do with prohibitions on behavior associated with earlier, polytheistic religious and cultural practices in an effort to distance Judaism, and then Christianity, from them. It is clear from the primary sources that same-sex relationships in many ancient cultures were viewed, overall, as simply an alternative to so-called heterosexual associations. As Christianity increasingly became the lens through which myths such as Ganymede were interpreted, same-sex couples were either modified, villainized, or erased from translations.

Even in the pre-Christian work of the Roman poet Virgil, Ganymede is depicted as a victim of abduction and rape who is taken by the eagle against his will while his fellow shepherds and his dogs cry out helplessly. In the world of the audience first hearing the myth, however, the message would have been clear and, also, inspiring.

To the ancient Greeks, the myth of Ganymede would have worked well as an exemplary tale of the lover-and-beloved same-sex relationship in that Zeus, the elder lover, elevates the youth Ganymede to the heavens in exactly the same way an older lover was to nurture and develop his younger beloved. The eagle was the symbol of Zeus, in one story it was created by Gaia, the Mother of All Things, and the image was used by Zeus on his standard. Whether Zeus becomes an eagle or sends an eagle to take Ganymede, the message would have been the same to an ancient Greek audience. The eagle was thought to symbolize the power and wisdom of Zeus and a person who was visited by an eagle was thought to be particularly blessed and elevated as Mireaux explains:

The language of the gods may take different forms. They may make their communication through the thunder, the winds, meteors and other portents, even a bird in flight. But they can and do employ also special emissaries to convey their message to man. (26)

In the myth, Zeus as an eagle or an eagle sent by Zeus seizes the unsuspecting shepherd and takes him to the realm of the gods. This would be comparable, to a modern-day audience, to winning the lottery at a point in one’s life when prospects seemed dim. Ganymede, for all his beauty, was, after all, the third son of Tros, and it would have been unlikely he would have had any hope of a large inheritance.

At best, he would have lived off the generosity of his older brothers in providing him with some lucrative position. Instead, he is translated from time to eternity by a god who then cares for and nurtures him. Once one removes the modern-day rejection of same-sex relationships from an interpretation of the story, it resonates clearly as a happily-ever-after tale even in those versions where Ganymede repudiates his favored position in order to bring peace to the gods and the water of life to humanity.

Conclusion

Ganymede would have been respected, and perhaps even envied, by an ancient audience who might have hoped for similar fortune to fall upon them. Mireaux comments:

As a rule, of course, the gods (apart from the gods of the hearth and of the fields, woods, and waters) have no direct and permanent relations with men…They establish relationships in different ways, as guides and counselors and as the bearers of warnings; although they may also deceive men and give them delusions. Many natural events are in reality signs employed by the gods, if one can but recognize and interpret them aright. (26)

Contrasted with this model of humanity’s interaction with the divine is Ganymede who is specifically chosen by the gods, or a god, for his beauty and granted immortality among the heavens. In the modern LGBTQ+ community, Ganymede continues to be a symbol of the kind of elevation that comes from love and being in love, which allows for the same flight of the soul toward the heavens the young shepherd experienced with the eagle of Zeus.