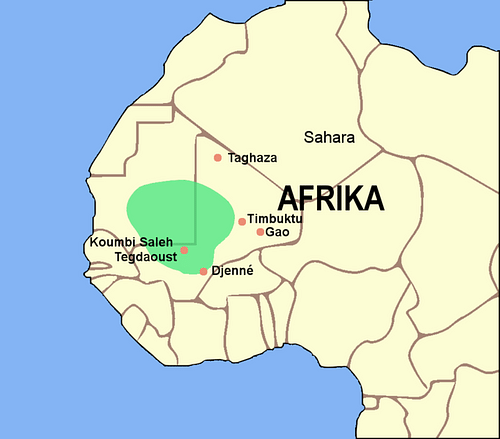

The Ghana Empire flourished in West Africa from at least the 6th to 13th century CE. Not connected geographically to the modern state of Ghana, the Ghana Empire was located in the western Sudan savannah region (modern southern Mauritania and Mali) sandwiched between the Sahara desert to the north and the rainforests to the south.

Trade in the Ghana Empire was facilitated by the abundance of iron, copper, gold, and ivory and easy access to the Niger and Senegal Rivers and their tributaries. The Ghana kings, residing in the capital at Koumbi Saleh, grew immensely rich, building up stockpiles of the gold nuggets only they were permitted to possess. Consequently, the reputation of Ghana spread to North Africa and Europe, where it was described as a fabulous land of gold. The Ghana Empire crumbled from the 12th century CE following drought, civil wars, the opening up of trade routes elsewhere, and the rise of the Sosso Kingdom (c. 1180-1235 CE) and then the Mali Empire (1240-1645 CE).

West Africa & the Sudan Region

The Sudan region of West Africa (not to be confused with the modern state of that name), where the Ghana Empire would develop, had been inhabited since the Neolithic period as is evidenced by Iron Age tumuli, megaliths and remains of abandoned villages. The Niger River regularly flooded parts of this dry grassland and savannah, which provided fertile land for agriculture beginning at least 3,500 years ago, an endeavour greatly helped by the region's adequate annual rainfall. Cereals such as red-skinned African rice and millet were grown with success, as were pulses, tuber and root crops, oil and fibre plants, and fruits. Fishing and the herding of cattle and goats were other important sources of food.

Local deposits of copper were exploited and used for trade, while metalworking in the region, as indicated by archaeological finds, dates back to at least the 6th century CE. There have been many finds, too, of fine pottery, some of which was traded across the region, as indicated by chemical analysis of the clay. Similarly, gold was probably locally mined or panned and then traded along the numerous waterways of the region, but concrete evidence from this early period is lacking. Indeed, the whole history of the region and the Ghana Empire before the 11th century CE remains vague due to a lack of written sources and the rather meagre results of archaeology. However, the latter has increased dramatically in the 21st century CE, and both the antiquity and extent of West African trade, in particular, are now considered to have been greater than previously thought.

Foundation

The precise foundation of the Ghana Empire, or the Kingdom of Ghana as it is sometimes referred to, is not known. It may date to as early as the 6th century CE but evidence of some sort of political apparatus is not seen until later. The period when the empire was at its height is considered to be between the 9th and 11th century CE. The name Ghana most probably derives from a local title meaning king.

The Ghana Empire was mostly composed of the Soninke (aka Sarakole) people, who spoke Mande (aka Mandingo) and who occupied the area of savannah between the Niger River (to the southeast) and Senegal River (to the southwest). These rivers and the Sahara desert to the north formed a natural triangle of flat grasslands that the Ghana Empire would occupy (today's southern portions of Mauritania and Mali). The region dominated by the Soninke is often referred to as Wagadu in indigenous oral traditions or as Wangara, the Muslim geographers' term for the Middle Niger.

Koumbi Saleh

The capital of the Ghana Empire was most likely Koumbi Saleh (in the absence of any other viable candidates). Also known simply as Ghana, it is located 322 km (200 miles) north of modern Bamako, Mali. The capital was much larger than previously thought - the medieval Arab descriptions of a population of 40-50,000 now looking conservative after recent excavations, which show the city spread over an area of 110 acres (45 hectares) with many other smaller settlements immediately surrounding it. Excavations have also revealed a significant mosque, a large public square, and parts of a circuit wall and monumental gateway. Housing was typically of one storey and made with mud-dried bricks, pounded earth and wood or stone, all used in the region since prehistory and still in use today. The Arab traveller Al-Bakri, visiting near the end of the empire's history in 1076 CE, describes the capital as being surrounded by wells and with irrigated fields where many vegetables grew. He goes on to state:

The king has a palace and a number of domed dwellings all surrounded with an enclosure like a city wall…Around the king's town are domed buildings and groves and thickets where the sorcerers of these people, men in charge of the religious cult, live. In them are their idols and the tombs of their kings.

(quoted in Fage, 668)

King & Government

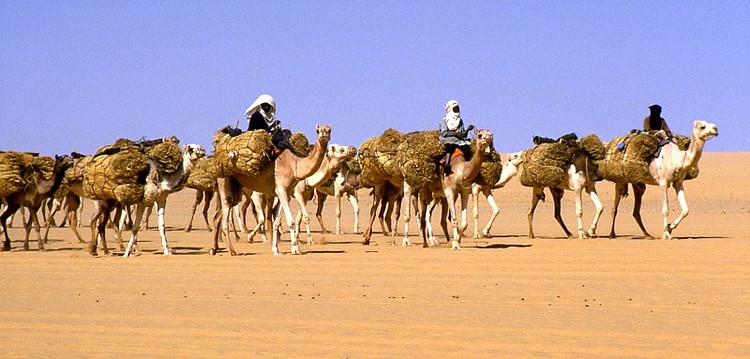

Really a conglomerate of villages ruled by a single king, the empire prospered thanks to a well-trained army which had cavalry units and access to raw materials such as iron ore to make its weapons and gold deposits to pay its soldiers. It is perhaps significant that blacksmiths and forgers have long enjoyed an elevated status in the Sudan region. Possession of camels with their utility as transport of goods and people was another factor in the superiority of the Soninke over their rivals. With these advantages, the Ghana Empire acquired new territories and new tribute from subjugated tribal chiefs, and they could monopolise first local and then regional trade.

The Ghana king was an absolute monarch and the state's head of justice and religion. There was a certain cultivated mystique about the ruler, partly due to his role as leader of the animist religion amongst his people. Sacrifices and libations were made in his honour, there were strict rules of etiquette in his presence and, when he died, his tomb was laid in a sacred grove which no person could enter. The traveller Al-Bakri described the Ghana king in the following terms:

The king adorns himself like a woman, wearing necklaces and bracelets, and when he sits before the people he puts on a high cap decorated with gold and wrapped in turbans of fine cotton…Behind the king stand ten pages holding shields and swords decorated with gold, and on his right are the sons of the vassal kings of his country wearing splendid garments and their hair plaited with gold.

(quoted in Krieger, 322)

The king did rely on advisors and, from the 11th century CE, even recruited Muslim merchants to act as interpreters and as officials who helped manage the economy and keep track of the goods coming in and out of the country.

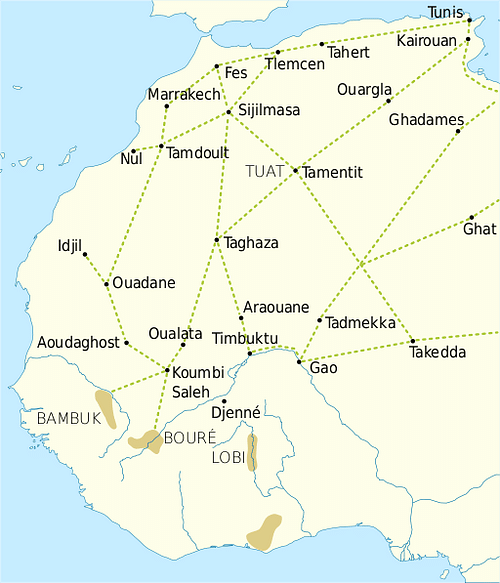

West African Trade

The Ghana Empire dominated central West African trade in the upper valley of the Niger River from the 6th or 7th century CE. Control of regional trade was a lucrative business for the kings of Ghana who passed on goods like gold, ivory, hides, ostrich feathers, and slaves to the Muslim merchants (particularly the Sanhaja Berbers) who sent camel caravans that crossed the Sahara from North Africa and which brought much-valued salt to the south. Goods were often taxed twice, once when they came into the country and again when they left it.

In addition to income from passing trade, the Ghana Empire had access to its own resources, notably iron ore and gold from the fields of Bambuk, which the elite used to exchange for such luxury goods as fine textiles, beads, copper, and horses, which were all brought by Arab traders from the north. Another commodity-currency used in Ghana, besides gold, was copper wiring. The kings of Ghana once again illustrated their supreme position by prohibiting anyone else but themselves from owning gold nuggets; merchants had to be satisfied with gold dust. The policy had the added advantage of ensuring the king could control the gold market and ensure its value did not decrease by having too much of it in circulation at any one time.

Muslim Influence

Islam was spread throughout the region by Muslim merchants as they came into contact with local traders and the elite of urban areas. Leaders may have recognised that adopting the religion (or seeming to), or at the least tolerating it would be beneficial to trade. Indeed, in the Ghana Empire, there is no evidence that kings themselves converted to Islam. On the contrary, Ghana's capital at Koumbi Saleh was divided into two distinct towns from the mid-11th century CE. One town was Muslim and boasted 12 mosques while the other, just 10 km away and joined by many intermediate buildings, was the royal residence with many traditional cult shrines and one mosque for visiting merchants. This division reflected the continuance of indigenous animist beliefs alongside Islam, the former being practised by rural communities.

Decline

The first stage in the decline of the Ghana Empire began in the mid-11th century CE. C. 1076 CE the capital was sacked by the Almoravids of North Africa (c. 1055 - c. 1147 CE), perhaps in retaliation for the Ghana rulers' attempt to muscle in on trade by Saharan commercial centres. The Ghana Empire struggled to recover thereafter; Muslim rulers may have been imposed by the Almoravids but concrete evidence is lacking for any sort of conquest. Meanwhile, towns like Awdaghost (est. 1055 CE) were lost to the Ghana kings and so permitted Berber merchants to directly control more of the region's trade.

The Ghana Empire really began to collapse in the 12th century CE. The decline set in when other competing trade routes opened up further east and when the climate became unusually dry for a prolonged period, which affected agricultural production. The rulers of Ghana did not help themselves either as the empire was beset by a string of civil wars, the divisions perhaps based on the inherent conflict between Muslim and animist beliefs. Meanwhile, many rebellious chiefs took the opportunity of a weak central government to declare themselves independent of the empire, notably Tekrur in the Western Sudan region which controlled the Senegal River and which had even allied itself with the Almoravids.

The kingdom of Sosso (aka, Susu, c. 1180-1235 CE) was the biggest inheritor of the crumbling Ghana Empire, aided by the collapse of the Almoravids in the mid-12th century CE. However, the Sosso would be a short-lived kingdom as their king Sumanguru (aka Sumaoro Kante, r. from c. 1200 CE) was defeated by Sundiata Keita in 1235 CE. Sundiata also seized the old Ghana capital in 1240 CE, and he would go on to found the Mali Empire (1240-1645 CE), the largest and richest empire yet seen in Africa.