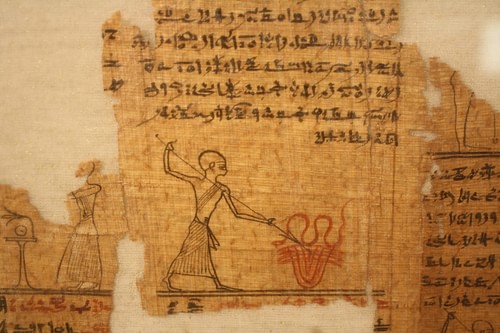

A text known as The Lay of the Harper, dating from the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) encourages its audience to make the most of the time because death is a certainty:

Make a holiday! And do not tire of playing! For no one is allowed to take his goods with him, and no one who departs this life ever comes back again (Tyldesley, 142).

The most enduring Egyptian view of death was that it was a paradise, a continuation of life on earth but lacking any disappointment, loss, or distress. Far from a "you can't take it with you" understanding, for most of Egyptian history the view was "you keep it forever" as one would find all one lost at death in the paradise of The Field of Reeds on the other side. This vision of the afterlife altered in different eras, sometimes being more widely accepted and sometimes less, but remained fairly constant. Along with this view went an understanding of disembodied spirits - ghosts - which, more so than the view of the afterlife, remained unchanged from the earliest evidence through the end of ancient Egyptian history: ghosts were as much of a reality as any other aspect of existence. Egyptologist Rosalie David writes:

It was believed that society consisted of four groups - gods, the king, the blessed dead, and humanity - who shared certain moral obligations and a duty to interact in order to maintain world order. The existence of this order, and the assumption that it was constantly under threat, was a basic premise of Egyptian belief (271).

The central value of Egyptian culture was ma'at (harmony, balance) which the Egyptians observed in virtually every aspect of their lives; among the more important of these was the proper burial of the dead. A human being was thought to be traveling on a one-way road from birth, through death, and on to the afterlife. Provision was made through tomb paintings, inscriptions, and statuary for the soul to return and harmlessly visit the earth but the spirit was expected to depart to its own realm relatively quickly. The appearance of a ghost, and especially its interaction with the living, was a certain sign that the natural order had been disturbed and the most common cause of this trouble was a spirit's dissatisfaction with its body's burial, the state of the tomb, or a lack of respectful remembrance.

The Soul in Ancient Egypt

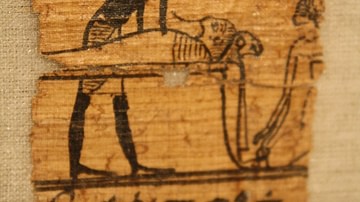

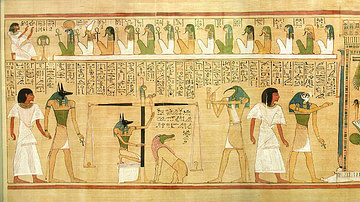

In early Egyptian belief, the soul was viewed as a single entity known as the Khu which was the immortal aspect of the person. In time it came to be recognized as being comprised of five different aspects, sometimes of seven, and sometimes of nine depending on the era in Egyptian history. The nine aspects form the general understanding informing the concept of the seven and five: the Khat was the physical body; the Ka one's double-form; the Ba a human-headed bird aspect which could speed between earth and the heavens; Shuyet was the shadow self; Akh the immortal, transformed self, Sahu and Sechem aspects of the Akh; Ab was the heart, the source of good and evil; Ren was one's secret name. The Khat needed to exist in order for the Ka and Ba to recognize itself and so when one died it was of the utmost importance that the body be preserved as intact as possible. It is this belief which led to the Egyptian practice of mummification.

When a person died, the family brought the body to the embalmers, the ancient equivalent of the modern-day funeral home. The body would then be cared for to the degree the family was able to pay. There were three options for embalming and burial from the top-shelf price which associated the corpse with the god Osiris to a lesser price, which included embalming, rites, and a coffin on a more modest scale, to the lowest price which provided the least amount of service.

The family's choice of these options would dictate the kind of coffin provided, the funerary rites the corpse was entitled to and, just as importantly, how the body was prepared for burial. Embalmers would present all three of these choices to bereaved families knowing that their choice could affect the deceased's afterlife as well as their own life in the coming months; if the family could afford the deluxe Osiris option, but chose instead to save money on the second or even third option, the spirit of the deceased had every right to return to complain. In cases such as these, the Akh was given license by the gods to return to earth and right the wrong.

The Akh could return for a number of other reasons besides a cheap burial with insufficient funerary rites, however. Any wrong which had been done to the deceased, which had not been atoned for in life, could be cause for a haunting after the person's death.

Returning Spirits

One of the best-known examples of a haunting in ancient Egypt comes from a letter written by a widower to the spirit of his dead wife found in a tomb from the Middle Kingdom. He writes:

What wicked thing have I done to thee that I should have come to this evil pass? What have I done to thee? But what thou hast done to me is to have laid hands on me although I had nothing wicked to thee. From the time I lived with thee as thy husband down to today, what have I done to thee that I need hide? When thou didst sicken of the illness which thou hadst, I caused a master-physician to be fetched…I spent eight months without eating and drinking like a man. I wept exceedingly together with my household in front of my street-quarter. I gave linen clothes to wrap thee and left no benefit undone that had to be performed for thee. And now, behold, I have spent three years alone without entering into a house, though it is not right that one like me should have to do it. This have I done for thy sake. But, behold, thou dost not know good from bad (Nardo, 32).

The man must have been enduring some suffering which could only be explained by the agency of his deceased wife. Illness and bad fortune were attributed to either the work of the gods (to teach one a lesson or punish some sin), activities of evil spirits, or the anger and resentment of the dead. In this case the widower claims to have done everything properly in his relationship with his wife even after she died stating he has even gone so far as to avoid visiting a brothel ("a house") in the three years since she has been gone. Brothels were practically non-existent in Egypt prior to the time of the Late Period and so his reference is assumed to be to an establishment like a bar or pub where prostitutes may have been found. There is not a great deal of evidence for prostitution in ancient Egypt on the whole, however, and the man could simply be referring to "a house" in the way one today would an ale-house or pub without any sexual implication, though the passage is generally not interpreted in that way.

In a case like this, the man would have gone to a priest or a "wise woman", a seer, to intervene or perhaps visited a temple. Rosalie David comments on this, writing: "Some temples were renowned as centres of dream incubation where the petitioner could pass the night in a special building and communicate with the gods or deceased relatives in order to gain insight into the future" (281). When these options failed, the living would resort to writing a letter. David continues:

An important means of contact with those who had passed into the next world was provided by the so-called 'Letters to the Dead'. People who considered that they had suffered injustice could write a letter to the dead, asking them to intercede on the writer's behalf. If a living person with problems had no powerful patron in this world, he could seek the help of the dead...the letters were placed in the tomb-chapel, at the side of the offering table where the deceased's spirit would find them when it came to partake of food. Requests found in the letters are varied: some sought help against dead or living enemies, particularly in family disputes; others asked for legal assistance in support of a petitioner who had to appear before the divine tribunal at the Day of Judgement; and some pleaded for special blessings or benefits (282).

Since the dead continued to exist in the afterlife, they could be contacted whenever the living needed them to; just because they could no longer be seen on earth was no reason to believe they had ceased to exist. Egyptologist William Kelly Simpson writes:

Death for the deceased Egyptian who had undergone the rites of beatification was an extension of life, and as the practice of festal banqueting in tomb chapels indicates, rapport between the living and the dead was by no means always a gloomy affair...Egyptian ghosts were not so much eerie beings as personalities to whom the living reacted pragmatically (112).

Khonsemhab & the Ghost

This kind of relationship is illustrated through a ghost story from the Ramessid Period (1186-1077 BCE) of the New Kingdom (1570-1069 BCE) whose title is usually translated simply as A Ghost Story but is also known as Khonsemhab and the Ghost. Although the extant version of the story dates from the New Kingdom it is thought to be a copy of an older piece from the Middle Kingdom. In this tale, the High Priest of Amun, Khonsemhab, encounters a spirit named Nebusemekh whose tomb has fallen into ruin. Nebusemekh is depicted as an individual with a problem; not as a ghost who has returned to haunt or trouble the living.

The story begins as Khonsemhab returns to his house, presumably after meeting the spirit by chance in the necropolis of Thebes. He summons the spirit to speak with him directly, finds out his name, and discovers his grievance: his tomb has deteriorated because the ground beneath it fell away and it collapsed. No one knows where he is buried and so no one brings him offerings anymore. Khonsemhab promises the spirit he will build him a new tomb but Nebusemekh is skeptical saying he has heard such promises many times before when he has complained about this to people. Khonsemhab sends servants who find the tomb and announces to an official his plans to build a new tomb for Nebusemekh. The end of the story is lost but it is assumed that Khonsemhab was as good as his word and Nebusemekh was provided with a new tomb.

This story, though fiction, is in keeping with the way ancient Egyptians believed they actually interacted with spirits. Khonsemhab is considered fictional, as is Nebusemekh's tale of his life on earth, but the plot of the story would not have seemed outlandish to an ancient audience. The purpose of the story, aside from entertainment, would have been to impress upon an audience the importance of honoring and respecting the dead through continued remembrance and care of their tombs. The story makes clear that Nebusemekh had been an important man in life whose tomb deserved continued maintenance and respect and, if this could be denied to someone like that - a man honored by so great a king as Mentuhotep II - then it could be denied to anyone. The moral would have reminded an audience that one should be careful to honor and respect the dead because, eventually, all would find themselves in that same state.

This Life & What Comes After

The afterlife, known most commonly as The Field of Reeds, precisely mirrored one's earthly life. The gods had created the most perfect of places when they made Egypt and Egyptians were granted the great gift of living there eternally after they had passed through death and the judgment by Osiris. As noted, this understanding of eternity would alter at times but that central understanding continued to weave its way through Egypt's long history.

In the Middle Kingdom, however, one finds texts which most sharply deviate from the belief in an eternal life of joy in the next world and this is reflected in lines which Khonsemhab speaks to the spirit of Nebusemekh:

How badly you fare without eating or drinking, without growing old or becoming young, without sunlight or inhaling northerly breezes. Darkness is in your sight each day. You do not get up early to leave (Simpson, 113).

This is a view one finds commonly expressed in Middle Kingdom literature: death may have been a certainty but what came after was not. The Egyptian view from this period, at least as expressed in the literature, is much closer to that of Mesopotamia where the dead lived on in an eternal twilight, drank from puddles, and ate dust. Unlike the traditional Egyptian view where one lived on as one always had, now the spirit was thought to have no connection to one's previous life. Khonsemhab's line, "You do not get up early to leave" would refer to one's earthly practice of rising in the morning to go to work. In the traditional view, one would have worked on in the afterlife at whatever one had done on earth. Tombs were always considered one's "eternal home" in Egypt from the mastabas of the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150-2613 BCE) to King Djoser's Step Pyramid (c. 2670 BCE) through the monuments of the Ptolemaic Dynasty (323-30 BCE) but in the Middle Kingdom they seem to be viewed widely as one's final destination.

Concern over the dead and returning spirits had always been a part of Egyptian culture but a certain skepticism marks the Middle Kingdom attitude and made ghosts a much more present threat to the established order in questioning an afterlife of eternal peace: if there was no paradise then where did people's souls go when they died? The most prevalent answer seems to be, nowhere. They remained in their tombs, their eternal homes. Ghosts no longer came from an afterlife to interact with the living; they were present in this life.

At this same time, as Egyptologist Gae Callender notes, there is seen an increase in personal piety. Individual expressions of devotion to the gods and one's duties begin to appear more frequently in tomb inscriptions during the Middle Kingdom. Callender writes:

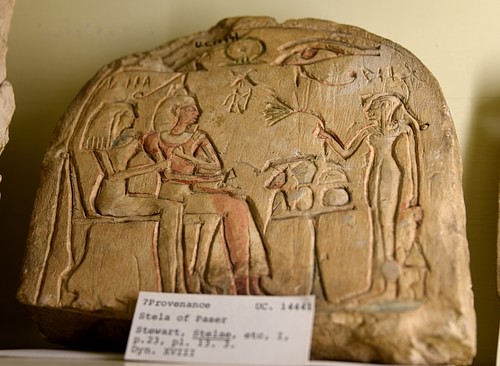

There was a noticeable emphasis on 'personal piety' (that is, direct personal access to deities rather than via the king or priests, a religious concept that further increased in popularity during the New Kingdom). Stelae from the Middle Kingdom stress the piety of their deceased owners and out of this grew the concept of the 'negative confession' (ritual lists of misdemeanors that the deceased claimed not to have committed). Stelae themselves became popular memorials, especially those decorated with wedjat-eyes, the paramount symbol of protection (Shaw,169).

Declarations of one's piety, carved in the stone marking one's tomb, would have been thought to ensure continued remembrance and care for the home of the soul. Lacking a certainty in an afterlife, the tomb took on even greater importance than it had previously. Simultaneously, as Callender notes, people began to develop the concept of a personal relationship with the gods who would look after their pious spirits in their tombs should the afterlife fail them. This all meant, among other things, that the spirits of the dead were considered closer at hand than before. People could have a personal relationship with ghosts in the same way they could with the gods.

This relationship is explored through a didactic text known as The Instruction of King Amenemhat I for his Son Senusret I. This document, dating to the early Middle Kingdom, is advice from the spirit of king Amenemhat I (c. 1991-1962 BCE) to his son Senusret I (c. 1971-1926 BCE) and may have been commissioned by Senusret I as a eulogy for his father. The document was once regarded as a genuine letter from the king to the prince but has since come to be understood as literature written after Amenemhat's assassination.

In this piece the ghost of the king tells his son how he died and gives him advice on how to rule successfully. As with A Ghost Story, the instruction of Amenemhat text mirrors the belief of the time that the dead could communicate directly with the living without a mediator. In this genre of literature, the dead were now writing letters and the living were the recipients. Ghosts were close by, watching, waiting to offer their help or ask for it, not in an afterlife on another plane but present, if invisible.

Even in those eras when the concept of the Field of Reeds seemed more of a certainty, ghosts were still a part of the Egyptian spiritual landscape; they just had to travel further to reach the living. Non-existence was terrifying to the ancient Egyptians and even the Middle Kingdom vision of an eternity of haunting one's tomb was preferable to no eternity at all. The continued existence of the soul after death was central to Egyptian understanding whether their attitude was "you can't take it with you" or "you keep it forever". The dead were as present as the living and commanded the same respect; and when that courtesy was not freely given they could make their feelings clearly known as ghosts.