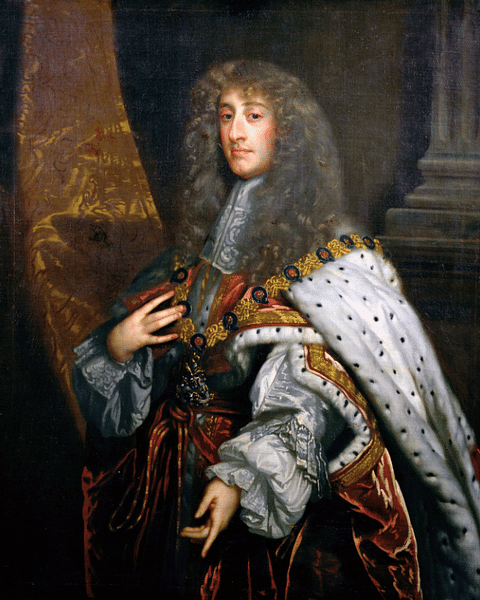

The Glorious Revolution of November 1688 saw Protestant William of Orange (l. 1650-1702) invade England and take the throne of Catholic James II of England (r. 1685-1688). There were no battles, and William was invited by Parliament to become king and rule jointly with his wife Queen Mary II of England (r. 1689-1694), daughter of James II.

James II's pro-Catholic policies and authoritarian rule had sealed his fate, and he lived thereafter in exile in France. Meanwhile, William and Mary ruled with the powers of the monarchy reduced and those of Parliament increased as part of a new system of government known as a constitutional monarchy, the system which is still seen today in the United Kingdom.

The main causes of the Glorious Revolution may be summarised as:

- King James II was a Catholic in a Protestant state.

- The king was biased toward Catholics in his key appointments.

- The king exceeded his authority in judicial matters.

- The king dismissed Parliament and never recalled it.

- The Declaration of Indulgences was seen as a protection of Catholic rights.

- A Catholic male heir was born superseding his elder Protestant sisters.

- A group of prominent Protestant nobles invited the Protestant William of Orange to become king.

- William of Orange feared a Catholic France and England would join forces against him, and so he wanted to become king.

Protestantism & Authoritarianism

To understand the events of 1688 and their significance, it is necessary to go back several monarchs in the timeline of British history. The thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland were unified when James I of England (r. 1603-1625) succeeded Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603). James was the first of the Stuart monarchs, and he was succeeded by his son Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649). So far so good, and mostly peaceful. Then Charles went and spoilt things with his authoritarian rule and dismissal of Parliament. The English Civil Wars (1642-51) developed, and ultimately, the support for the novel idea of a republic and not simply a limited monarchy began to increase. An unrepentant and uncompromising Charles was executed on 30 January 1649. As it turned out, the 'commonwealth' republic led by Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) was just as unpopular as Charles had been. The late king's son Charles triumphantly returned to England and the throne with the Restoration of 1660. The monarchy was back. Unfortunately, it had not learnt any lessons from the disastrous events of the previous decades. Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685) died in 1685, but he had no children. As a result, the king's younger brother became King James II of England. The Stuart line was continuing as usual, but all was not what it seemed. Besides Parliament having grown in importance over the last 50 years, the old problem that had plagued the British Isles since the reign of Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547) was back with a bang: Protestantism versus Catholicism.

Charles II had been a Protestant; the problem was that his successor was a Catholic. James II had converted to Catholicism in 1668, and many feared that he wished to return England to being a Catholic state. Historians continue to debate what exactly were the king's intentions. James knew full well the importance of the matter, Parliament had even removed him from the succession for his faith back in 1679 (the Exclusion Crisis), but his brother had him reinstated. The reinstatement included the promise that James raise his two surviving children, Mary (b. 1662) and Anne (b. 1665), as Protestants.

With everyone preferring the peaceful and less wearisome option of continuing the status quo, the 51-year-old James was allowed to take the throne in 1680. The king even eliminated the communion part of his coronation. His supporters were cheered, the neutrals knew not who else to support, and his enemies hoped his reign would be short and his Protestant daughter Mary could then ensure the achievements of the English Reformation remained intact.

Rebellion

James experienced his fair share of trouble with two rebellions early on in his reign. The first was in Scotland in May 1685 when the Presbyterian Earl of Argyll, leader of the Campbells, led an uprising against the king in Scotland. Argyll was captured while marching to Glasgow, and the rebellion fizzled out. It is very likely that this uprising was intended as a parallel action to another, more serious one in the south of England, the Monmouth Rebellion of June-July 1665.

James Scott, Duke of Monmouth (b. 1649), was the illegitimate son of Charles II. He had already been involved in a plan to take the throne, the Rye House Plot of 1663 when a group of veteran Parliamentarians from the Civil War tried to assassinate Charles II and his brother after a race meeting at Newmarket. The plot was poorly planned and failed, Monmouth was exiled to the Netherlands for his involvement. Now Monmouth was back and with him 80-odd other disgruntled exiles. The motley crew landed at Lyme Regis in June and began to recruit men for an armed rebellion. There was sufficient ill-feeling towards James II that Monmouth managed to raise up to 4,000 men for his army, but it was an amateurish and poorly equipped one. A Royalist army easily defeated the rebels at Sedgemoor in Somerset on 6 July. Monmouth was captured and executed, despite his pleas for clemency from his uncle. James was ruthless in hunting down anyone with even the remotest connection to the Monmouth Rebellion. A few hundred were hanged, 850 were deported for hard labour in the Caribbean, and countless more were flogged. The hearings for those accused became known as the 'Bloody Assizes'. Although harshly punishing rebels was not unusual, the bloody vengeance did nothing for the king's popularity.

Indulgences & Appointments

Both the Argyll and Monmouth rebellions had been relatively minor affairs but they should have been warning shots of what might develop. Instead, the king's policies veered even more towards Catholicism. James relentlessly appointed Catholics in key positions in the government, courts, navy, army, and even universities. James also ignored some laws, extended others, and waived sentences when they applied to Catholic individuals he favoured, what became known as his Dispensing and Suspending powers. Parliament protested at these policies, and the king responded by dismissing the House in November 1685; it would not be recalled until there was a new monarch on the throne.

Another controversial decision was the April 1687 Declaration of Indulgence (aka Declaration of the Liberty of Conscience). This declaration actually improved religious toleration for all faiths, but many Protestants saw it only as a means to improve the status of Catholics. The king did not instil much confidence in non-Catholics when he declared in 1687: "we cannot but heartily wish, as it will easily be believed, that all the people of our dominions were members of the Catholic Church" (Miller, 332). To make matters worse, James reissued the Indulgence in 1688 and insisted it be read out in all churches. The Archbishop of Canterbury and six other bishops protested at this, but the king merely locked them up in the Tower of London. They were then put on trial, but this backfired when they were acquitted, and there was much public celebration.

A Catholic Prince

Besides Protestants having to accept a Catholic king, they also had to endure a Catholic queen and then a Catholic heir to the throne. James had married his second wife, Mary of Modena (d. 1718), in 1673; there were even wild rumours that the queen was actually the daughter of a pope. Then perhaps the final blow for the more militant Protestants fell. The king, after enduring the tragedy of many of his offspring dying in childbirth or early childhood, had a son. James Francis Edward was born on 10 June 1688. This meant that neither Mary nor Anne would become the next monarch, and with both parents being Catholic, it seemed a certainty Prince James would be raised in that faith. So convenient was this event for the king, many suspected the child was not his own but had been brought in for the sole purpose of perpetuating Catholicism in England. The fact that Prince James' godfather was Pope Innocent XI was another unnecessary provocation. Those Protestants who had been calling for restraint until the aged king died and Protestant Mary took over now had no argument. Rebel Protestant nobles knew that they must act now or never.

A Protestant Prince

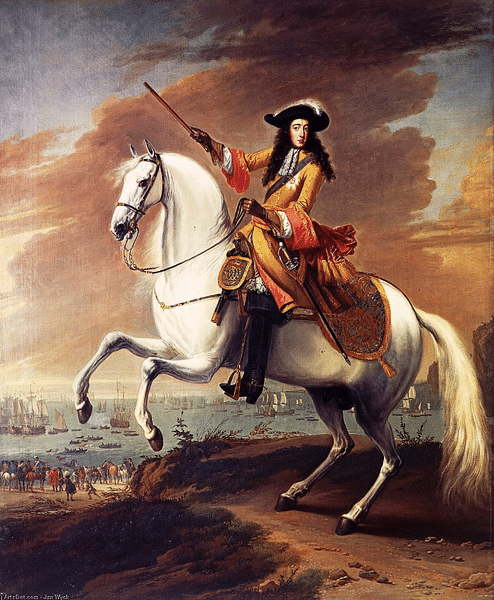

The burning question was not necessarily how to depose the king but who would replace him. Rebel nobles looked abroad. On 30 June, a group of seven, who included the dukes of Devonshire and Shrewsbury and the Bishop of London, got together and contacted Protestant Prince William of Orange via the Dutch ambassador in England, inviting him to become king of England, Scotland, and Ireland. William had several points in his favour besides his religion. He was the grandson of Charles I of England and had married James II's daughter Mary in 1677. William was no doubt delighted at the offer since he was already planning on invading. Having built up a sizeable navy, the prince said that he was merely waiting for a favourable "Protestant wind". His prime motivation was to avoid England becoming Catholic and then joining forces with the French to attack the Netherlands.

William's first attempt to reach England by sea was scuppered by stormy weather, but he persisted and landed with an army of 15-21,000 men in Devon on 5 November 1688. The army was an experienced fighting force and made up of Dutch, English, Scots, Danes, Huguenots, and even a contingent from Suriname. The prince also took a printing press so that he might more easily spread pro-Protestant propaganda. When he landed at Brixham, William reassured the Englishmen he met that "I come to do you goot. I am here for all your goots" (Cavendish, 338).

William marched slowly east towards London through unfavourable weather. Meanwhile, James was left isolated, deserted by former supporters like John Churchill and even his own daughter Anne. The queen left England for the safety of France in December. James suffered more important desertions amongst his top army staff, and there were immediate uprisings in favour of William in Cheshire, Yorkshire, and Nottinghamshire. Then after being hit with a bizarre series of nosebleeds, the king decided to abandon the battlefield and follow his wife. The king may have been suffering a mental breakdown at this point as he became utterly convinced he was destined to suffer the same terrible fate as his father. Queen Mary made it across the Channel, but the king did not, despite his disguise as a woman. He was spotted by fishermen and taken captive in Kent. William was by now in London, and he decided the best thing to do with his rival and father-in-law was to allow him to leave for France as he had wished. William had achieved the remarkable feat of heading the first successful invasion of England since his namesake William the Conqueror (r. 1066-1087) in 1066.

A Constitutional Monarchy

The official line was that James had abdicated, and Parliament recorded the removal of the monarch as occurring on 23 December 1688, the day James had left English shores. William became William III of England (also William II of Scotland, r. 1689-1702) via a decree by Parliament on 13 February 1689. This change of regime became known as the Glorious Revolution because it had occurred entirely peacefully (or almost, there were some episodes of Catholic houses and chapels being attacked during William's march to London). There had certainly been no battles or country-wide uprisings in support of either side. Whig historians (pro-Protestants) also believed the revolution 'glorious' because it had preserved the existing institutions of power, which was true, but the relationship between these institutions was altered, a change which only grew more significant over time.

There were some limitations to William's golden prize. The first was that William had to rule jointly with his wife, now Mary II of England, although in practice he alone had sovereign power. The 'Tories' in the House of Lords (the upper chamber of Parliament) had wanted Mary to rule alone as this preserved the tradition of succession, but William would not settle for anything less than a proper king's role. The second limitation was imposed by Parliament as a new form of government was devised, a constitutional monarchy. Over the next few years, a whole barrage of laws passed by Parliament limited the monarchy's powers. Gone were the days of authoritarian monarchs who could dismiss Parliament on a whim. Now the two institutions ruled in unison, an arrangement established by the Bill of Rights of 16 December 1689.

Parliament had the ultimate authority in the key areas of passing laws and raising taxes. It also became much more involved in accounting how money was spent for state purposes, particularly on the army and navy. The monarchy was now supported not by the taxes they could raise or the land they could sell but by the money from the Civil List issued by Parliament, beginning with the Civil List Act of 1697. William may not have liked this control on his purse strings, but it meant he could not, as so many of his predecessors had done, dismiss Parliament for long periods and only call it back when he ran out of cash. And the king needed lots of cash since he was determined to use his new position to finally face the French on the battlefield and end their domination of Europe; so began the Nine Years' War (1688–1697).

The list of limitations on William in Britain continued. No monarch could henceforth maintain their own standing army, only Parliament could declare war, and any new monarch had to swear at their coronation to uphold the Protestant Church. No Catholic or individual married to a Catholic could ever become king or queen again. To ensure Parliament did not itself abuse the power bestowed upon it, there were to be free elections every three years and a guarantee of free speech in its two Houses. Finally, the May 1689 Toleration Act, although it did not go as far as Calvinist William had hoped, protected the rights of Protestant dissenters (aka Non-Conformists) who made up around 7% of the population. After a period of persecution under the Stuarts, they could now freely worship as they wished and establish their own schools. The Toleration Act did not apply to Catholics or Jews.

Ireland & Scotland

James II was not dead but in exile, and eventually, encouraged by Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715) he made an attempt to get his throne back. Landing in Ireland in March 1689, James had some early success, but a 105-day siege of Protestant Londonderry (Derry) failed. Then the arrival of the king in person with a large English-Dutch army, which was superior to James' in both weapons and training, brought final victory at the battle of Boyne on 1 July 1690. Ireland was 75% Catholic, and although a guerrilla war rumbled on, the country found itself once again with a Protestant king.

In Scotland, Jacobite support (for James II, from the Latin Jacobus) had been particularly strong in the Highlands, but in the cities, there was more support for Protestant William. When the Prince of Orange had first landed in England, there were shortly afterwards sympathetic riots in Edinburgh where Catholics and their property were attacked. A Convention met to decide who to support, and the decision was made on 11 April 1689 to favour William. At the same time, the Claim of Right established the monarchy there on similar terms as declared in the English Bill of Rights. Mary and William ruled jointly in Scotland when they accepted the crown there on 11 May 1689. There was a Jacobite rising led by Viscount Dundee which defeated a pro-William army at Killiecrankie in July 1689. Then there was a reversal in August at Dunkeld where 'Bonnie' Dundee was killed. In the meantime, the government of Scotland was established under the control of the Presbyterian Church.

In 1692, the divisions in Scotland were widened when James' supporters the MacDonald clan had its leaders massacred at Glencoe by the Campbells. James II died in exile in France in 1701, but his son James (the Old Pretender) and grandson Charles (the Young Pretender) both carried on the flame of rebellion in the Highlands. However, two Jacobite risings in 1715 and 1745 failed, and there was no way back for the troubled Royal House of Stuart.

The three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland were now tied together more strongly than ever, at least in terms of politics and governance. William, Mary, and Parliament had created a new form of monarchy and government, one which provided a political, religious, and economic stability never before enjoyed. The Glorious Revolution thus ultimately "transformed Britain from a divided, unstable, rebellious and marginal country into the state that would become the most powerful on the planet" (Starkey, 399).