Aethelflaed (r. 911-918 CE) was the daughter of King Alfred the Great of Wessex (r. 871-899 CE) and became queen of Mercia following the death of her husband Aethelred II, Lord of the Mercians (r. 883-911 CE). She is best known as the “Lady of the Mercians” who defeated the Vikings and established English rule which would be consolidated by her brother Edward the Elder (r. 899-924 CE) and lay the foundation for the reign of the first recognized English king, Aethelstan, who was king of the Anglo-Saxons 924-927 CE and King of the English 927-939 CE.

Aethelstan is recognized by later historians as a pivotal figure in British history for his achievements in defeating the last of the Viking strongholds, centralizing the government, and establishing Britain as a potent force in European politics. It is unlikely, however, that he would have been able to accomplish what he did were it not for the influence of Aethelflaed of Mercia.

Her reign was so effective that she would eclipse those of contemporaries such as her brother Edward the Elder in Wessex and, in her own time, she seems to have been more widely respected than even her famous father. Aethelflaed continued the policies initiated by Alfred in accord with Aethelred but, after her husband's death, ruled on her own as she orchestrated the policies and practices which resulted in diminishing the power of the Danes in Britain and allowed for unification of the land under Edward and later Aethelstan.

Youth & the Viking Wars

Nothing is known of Aethelflaed's youth and she only enters the pages of history at the age of 15 or 16 when she was married to Aethelred. Her probable date of birth is 870 or 871 CE based on the approximate date of her marriage. Her name most likely means “overflowing with nobility” according to scholar Joanna Arman (32). “Aethel” means “noble” but the meaning of “flaed”, again according to Arman, is unclear but “could mean something like `flood', or something flowing over.” (32). Her name has also been translated as “noble beauty”.

Aethelflaed's mother was Ealhswith, a noblewoman of Mercia. Ealhswith came from a long line of Mercian nobles just as Aethelflaed's father, Alfred, was descended from the royalty of Wessex. Sources regularly cite Aethelflaed as Alfred's oldest daughter but it is unknown whether she was also his oldest child. Her brother, Edward, appears to have been younger than she was.

There can be little doubt, however, that Alfred's children were brought up in an atmosphere of piety, scholarship, and devotion to family and country which were all defining characteristics of the king. Arman notes how young women who dedicated themselves to the church and renounced the world were provided with a good education but that “there are allusions to all of Alfred's five children, including his two daughters who did not go into the church, having enjoyed an education.” (74).

In the same way that her brother Edward was provided with a tutor, so too may Aethelflaed have been. It is apparent from her later rule and court life that she was highly educated and cultured. It is unlikely, however, that Alfred himself would have spent much time with his daughter as he was occupied throughout her childhood fending off Viking incursions into Wessex.

The Vikings had first appeared in Britain in 793 CE when they landed on the coast and sacked the priory of Lindisfarne, slaughtering the monks and carrying off anything of value. From that time on, Britain was at the mercy of these raiders from the sea who struck without warning, slaughtered without discrimination, and plundered at will.

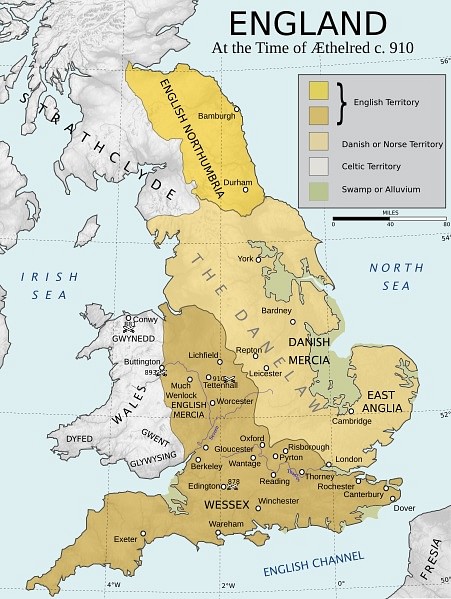

By the time Alfred was a prince and military commander, c. 865 CE, these raids had transformed into full-scale invasions under the leadership of skilled warriors like Halfdane (865-877 CE) and his brother Ivar the Boneless (c. 870 CE). These two commanders led the massive invasion of the Great Army in 865 CE which proved itself invincible, defeating every force thrown against it, and conquering every region they entered.

Alfred and his brother, Aethelred of Wessex (r. 865–871 CE), met the Vikings in battle at Reading and were defeated but at The Battle of Ashdown in January of 871 CE their combined forces drove the Vikings from the field and proved Alfred's skill in battle. His victory did nothing to halt the Viking incursions, however, and he was afterwards defeated and driven into hiding.

Alfred's Exile & Aethelflaed's Marriage

It is unknown whether Aethelflaed would have accompanied her father into exile. The sources - which only focus on the king and not on his family - only note that Alfred traveled in secret, and often disguised, with a small company of men. He was forced into this position by a Viking raid on Chippenham led by the Viking warlord Guthrum (died c. 890 CE) in 878 CE which caught him and his army completely by surprise.

Alfred and his family were at Chippenham celebrating Christmas when the attack was launched and, since anyone who did not manage to escape was killed or enslaved, it is more than probable that Alfred took his family with him when he fled.

After a few months in hiding and conducting guerrilla raids on Viking settlements, Alfred was able to mobilize a sizeable force and defeated the Vikings under Guthrum at The Battle of Eddington in May 878 CE. This was the decisive engagement which gave Alfred the power to finally dictate terms to his opponents who, thus far into his reign, had consistently held the upper hand. Guthrum and thirty of his chieftains were baptized as Christians as part of the treaty and they swore not to raise arms against Wessex again.

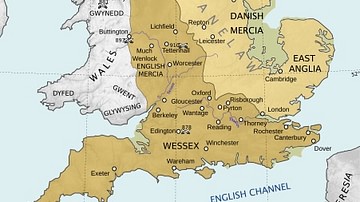

Although the Vikings kept their word and stayed clear of Wessex, the treaty in no way stipulated that they had to leave Britain; and so they stayed and fortified previously established settlements in Northumbria, East Anglia, and Mercia. In 886 CE Alfred drove the Vikings from London and secured it and, shortly afterwards, arranged the marriage between his eldest daughter and the king of Mercia, Aethelred.

Marriage & Birth of Aelfwynn

Although it is sometimes claimed that Aethelflaed's marriage was arranged to secure an alliance between Wessex and Mercia, this is inaccurate. The two regions were already allied by the marriage of Alfred and Ealhswith decades before and Aethelred had already accepted Alfred as his lord prior to 886 CE. A more accurate understanding of the marriage is that it was a display of unity which not only renewed each region's commitment to the other but made a clear statement of strength to the Vikings.

Aethelred was at least ten years older than Aethelflaed and had probably been betrothed to her early on. He had accepted Alfred as his overlord as early as 883 CE following Alfred's victory at Eddington. Aethelred is referred to as a great Christian warrior who fought against the heathen Vikings but there is no record of how he became king of Mercia. However it happened, he had control of the region by the 880's CE and was a powerful warlord at the time of the marriage.

Aethelred and Aethelflaed began their reign from the city of Gloucester, not far from Wessex, and close to her family's estates. Even though later romantic traditions would come to characterize their union as a loveless marriage of convenience, there is no evidence for this claim. They had one daughter, Aelfwynn, who is first named on a land charter in 903 CE but was not old enough to sign it as a legal witness. She may have been born shortly after the marriage but her birth date is unknown. William of Malmsbury, writing much later, claims that the birth of Aelfwynn almost killed Aethelflaed and she took measures to make sure she had no more children.

Aethelred & Aethelflaed

Aethelred and Aethelflaed worked in accord with Alfred of Wessex and mirrored his Burghal System of defense - in which fortified towns could easily be reinforced by others within a day's march - as well as his educational policies. Following Alfred's lead, they invited men of learning from other countries to Mercia to teach their clerics Latin and further other educational goals. They also restored, improved, and rebuilt cities and towns which had been damaged or destroyed during the Viking Wars.

The peace Alfred had won from the Vikings at Eddington and then at London, however, were only temporary respites in the struggle between the people of Britain and the Norse invaders. Although the period afterwards was somewhat less stressful, Viking raids and difficulties between Viking settlers and others continued, and in 892 CE the situation worsened when a new host of Viking raiders arrived under the leadership of the Viking raider Hastein (also given as Hasting). Alfred and Aethelred fought repeated engagements against Hastein from 892 CE until Hastein disappears from history in 896 CE. He may have been killed in battle but it seems this would have been noted; most likely he either left Britain or died of natural causes.

King Alfred died in 899 CE and was succeeded by his son Edward. Edward sent his son, Aethelstan, to the Mercian court in 900 CE to be raised by Aethelred and Aethelflaed alongside their daughter. Aethelstan would remain in Mercia throughout his younger years, educated at the court with his cousin Aelfwynn, and would later gain military experience on campaigns with Aethelred and then with Aethelflaed.

The king and queen of Mercia were great patrons of the church and freely endowed different priories and churches with large sums of money. They sent a raiding party into hostile territory to retrieve the bones of St. Oswald – the pious king of Northumbria who had founded the priory of Lindisfarne – and built a priory to house them at Gloucester. They would both be interred in this building, close by the relics of the saint, after their deaths.

They were especially generous to the church at Worcester who, in return, agreed to pray for them and dedicate services or at least psalms to their honor and for their continued health. In spite of these prayers, around 902 CE, Aethelred was stricken with a disease which seems to have incapacitated him. It would worsen over the next few years and, during this time, Aethelflaed effectively ruled alone.

The Battle of Chester

Sources from this period reference Aethelred's illness and make clear that Aethelflaed was the defining power in Mercia. The most famous story comes from the Irish Annals and recounts how, in 907 CE, a Norwegian Viking named Ingimund came from Ireland with his troops to “Aethelflaed, Queen of the Saxons, for her husband Aethelred was sick at that time” asking for a place he could peacefully settle in (170).

She granted him lands near the city of Chester but, after he had settled his people there, he noticed there were even more attractive areas around what he had been given. He then complained to the neighboring Danes and other Norwegians that he had been given too little when he deserved so much more and initiated a plan to take Chester by force.

Aethelred is mentioned repeatedly throughout this story as being “sick”, “very sick” or “sick and on the verge of death” (171-173). Messengers arrived at the court to tell the queen about Ingimund's plan and, even though Aethelred is cited as party to the response, it seems to have been Aethelflaed who prepared the battle plan that saved the city.

She first gathered a large army and then instructed the people of Chester on how to deploy the troops outside the city and fight with the gates open. Inside the city walls a much larger troop of cavalry would be stationed and, at a given point, the army outside should give way before the Vikings and retreat through the open gates where the troop of horse would be unleashed on the invaders.

At the same time, Aethelflaed wrote to the Irish who had allied themselves with Ingimund and appealed to them as friends who had been wronged by a common enemy. She asked them why they were fighting in the interests of those who had invaded their own country against her people who had never done them any wrong and further suggested the Irish chiefs should ask the Vikings what lands and goods were promised them for risking their lives in a cause not their own. Her letter was effective and, either just before or during the battle, the Irish switched sides.

The defense of Chester worked almost as Aethelflaed had planned. The defenders retreated and the cavalry massacred the Vikings who followed them. The attackers refused to give up, however, and the battle went on as the people of Chester defended the city by pouring boiling hot beer down on the Vikings from the walls. When the Vikings defended themselves with shields, the defenders hurled down the hives of honey bees while continuing to scald the Vikings with beer until the attack was called off and the city was saved.

Lady of the Mercians

Aethelred died in 911 CE with no male heir and Aethelflaed became sole ruler under the title “Lady of the Mercians”. In Asser's Life of King Alfred (written c. 893 CE), the author goes on at length regarding the custom in Wessex of not allowing a woman to sit as queen alongside a king because of a former queen who abused her power and position. In Mercia, however, the queenship had long been respected even though no woman had ever ruled the kingdom alone before. It is to Aethelflaed's credit that there is no record of any challenge to her succession.

Her brother Edward either took or received London and the surrounding lands from her shortly after Aethelred's death and this transaction has been interpreted by some later historians as sealing a deal in which Edward recognized the legitimacy of Aethelflaed's reign. Edward and Aethelflaed worked together afterwards to enlarge the burh system of both their regions and join them together for a tighter network of defense.

Arman notes how “they occasionally brought armies with them to clear their paths of any Vikings” (160). Edward's burhs were constructed as a show of kingly authority and military strength while, according to Arman, Aethelflaed had a different focus:

Aethelflaed seems to have been asserting her lordship by ensuring her kingdom was well defended. Her new burhs were more than just defensive structures, however; they were also planned towns. Inside the walls of many burhs the streets were laid out neatly according to the old Roman pattern, with four main streets intersected north to south and east to west and smaller side streets veering off them. People were encouraged to settle, and the men who served in the garrison may have been given `burgage' plots within the town where they could live with their families. (162)

Aethelflaed oversaw the construction of these burhs between 912-917 CE while also fighting off Viking attacks and attending to the business of governing Mercia. In 909 CE, Edward had launched an offensive into the Danelaw in which the soldiers sacked villages and slaughtered inhabitants for over a month. In retaliation, the Vikings struck back at Mercia.

In 916 CE, an abbot named Ecgberht was murdered along with his companions while possibly on a diplomatic mission from Mercia to Wales. Arman, citing the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, writes, “Aethelflaed's response was swift, decisive, and ruthless. Within three days, we are told, she had raised an army and marched them into Wales.” (191).

In 917 CE she again took the field at the head of her troops in a campaign against the Danes of Derby and was victorious. The next year she marched on Leicester which surrendered without a fight and these victories convinced the Danes of York to submit to her rule peacefully. The leading men of York were preparing for a formal submission when Aethelflaed died at Tamworth, possibly of a stroke, on 12 June 918 CE.

Legacy

Her daughter Aelfwynn succeeded her but only for a few months before she was deposed by Edward who claimed Mercia for Wessex and united the regions under his rule. Aelfwynn was brought to Wessex by Edward but what happened to her after that is unknown. The Mercians opposed domination by Wessex and it seems likely that Edward positioned his son Aethelstan – who by that point was more a prince of Mercia than Wessex – as a mediator at this time. When Edward died in 924 CE, his son by a second marriage, Aelfweard, succeeded him but died only 16 days later.

Aethelstan was proclaimed king by the Mercians and was then reluctantly accepted by the nobles of Wessex to become King of the Anglo-Saxons and, eventually, the first recognized king of the English people. Among his early achievements was completing the work Aethelflaed had begun by conquering the city of York and uniting England under a single ruler in 927 CE.

Aethelstan had grown up at the court of his aunt and uncle in Mercia. His education had been entirely their responsibility and, most likely, this fell more to Aethelflaed than her husband. Aethelstan's great achievements in education, law, foreign policy, and building projects would all have been influenced by his early years in the court of Mercia.

Historians two centuries later would write of Aethelflaed as a great ruler, far more than they would of Edward or even Alfred the Great, and acknowledged her influence over the prince who became the greatest king of his age. These same historians, most notably William of Malmsbury, also recognize Aethelflaed's significance in her own right as a woman who effectively ruled her kingdom during a time of crisis and left a lasting legacy for her people not only through her influence on her nephew but chiefly by her own accomplishments.