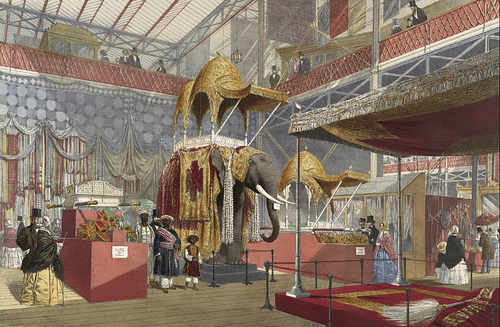

The 1851 Great Exhibition was held in the purpose-built Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, to showcase the latest developments in engineering, science, and the arts, as well as objects of cultural significance from Britain and abroad. Running from May to October, the exhibition was a huge success with more than 6 million people marvelling at the curiosities on show.

The Great Exhibition is the short informal title; the full name was the 1851 Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations. It was also known as the Crystal Palace Exhibition in reference to the building which housed it. The project was the brainchild of Albert, Prince Consort (1819-1861), husband of Queen Victoria (r. 1837-1901). The exhibition was planned and organised by the Royal Society of Arts and involved many key figures of the day, but it was Albert, the head of this society, who was its driving force.

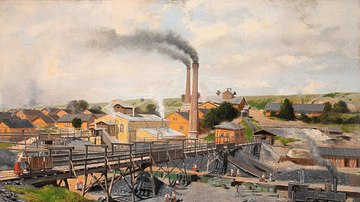

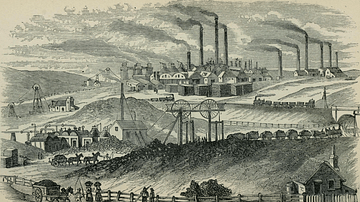

The idea was to showcase the industrial progress seen in Britain and other countries, which was the result of the Industrial Revolution, as well as other items of cultural interest. Nothing like it had ever been organised before. A runaway success, the exhibition raised funds which were used to found various museums and institutions, many of which still thrive today.

Albert's Vision

Prince Albert was a great believer in the idea that technology was capable of making the world a better place. He was President of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce and had already been organising annual exhibitions for this body. These exhibitions were limited to British engineering and cultural developments, and Albert wanted something more international to reflect the increasing reach of the British Empire. There were those who doubted such an exhibition was logistically possible, but Albert was determined. He wanted, above all, to show that human innovation, communication, and understanding between nations could achieve a better world. In his own words:

The Exhibition of 1851 is to give us a true test and a living picture of the point of development at which the whole of mankind has arrived in this great task, and a new starting point from which all nations will be able to direct their further exertions.

(Starkey, 461)

High ideals indeed, but the first practical problem was to raise the necessary funds for such an ambitious project. An organising committee was set up. Besides Albert, another key figure in the project was the civil servant Sir Henry Cole (1808-1882), a man of tremendous energy, who had reformed the postal system and helped make Victorian Christmas cards such a staple of part of the festive season. Other committee members were famous figures of the day, including two prime ministers: William Ewart Gladstone (1809-1898) and Robert Peel (1788-1850). The celebrated civil engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859) was another key figure involved in the project. The money was ultimately found through subscriptions, and there was even a reserve fund in case the exhibition was a financial disaster. The next problem to solve was where exactly such a gigantic exhibition could be hosted.

The Crystal Palace

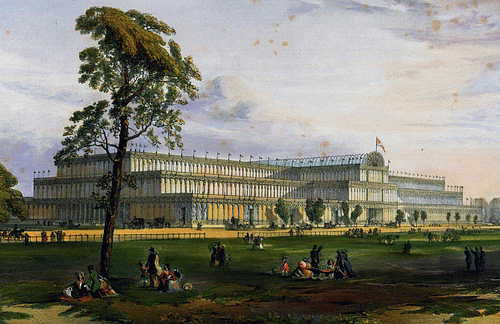

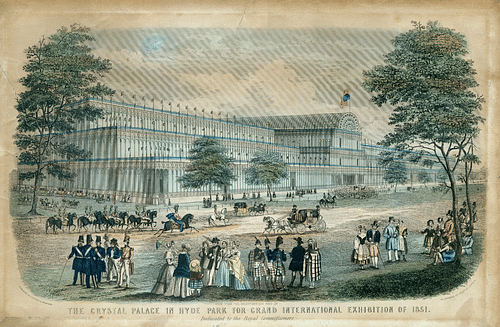

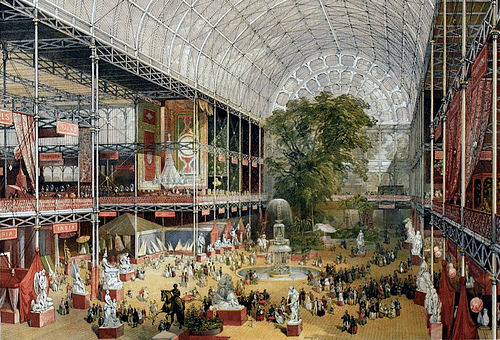

Several existing venues for the proposed exhibition were put forward. In the end, it was decided a purpose-built structure was needed, and there was a call for design proposals. There was certainly interest from architects in the exhibition as the organising committee received 245 projects for consideration. An entirely new challenge of matching design with function, the time and cost limitations were real problems to overcome. In addition, even the most optimistic of supporters insisted that a purpose-built structure must be a temporary one. These three factors decided the final choice of design which was a structure made of sheet glass with a cast iron framework, much like a giant greenhouse or conservatory. So the Crystal Palace was born, its name first coined by Punch magazine. It was designed by Sir Joseph Paxton (1801-1865), an architect and horticulturalist, who had built a similar structure on a much smaller scale at the home of the Duke of Devonshire, Chatsworth House.

To be located in Hyde Park, London, the project remained a massive undertaking. Again, critics in the press and now even in Parliament predicted a catastrophe both for the building and the ancient elm trees of Hyde Park. As Albert wrote, "I am more dead than alive from overwork. The opponents of the Exhibition work with might and main to throw all the old women into panic, and to drive myself crazy" (Woodham-Smith, 313). The committee pressed on, and, as the design of the Crystal Palace was published in the press and the giant structure began to take shape in Hyde Park, so the public anticipation and enthusiasm grew.

The massive pre-fabricated structure of the Crystal Palace was built by Fox, Henderson, & Company. It had both glass walls and roofing supported by iron framing set on concrete foundations. Half a million sheets of glass and 4,500 tons of iron were used in the construction. The structure took just four months to complete and created two levels of exhibition space covering almost one million square feet (93,000 m²). The height of the building was an impressive 108 feet (33 m) at its tallest point, 408 feet (124 m) at its widest, and 1,848 feet (564 m) in length. The interior was divided up to provide some 1.75 miles (2.8 km) of galleries. Above the building, proudly declaring the international nature of the exhibition, flew the flags of all nations. The completed building – all shimmering glass in the spring sunlight and with its ironwork painted a light blue – was a wonderful attraction in itself and it inspired authors such as William Makepeace Thackeray (1811-1863) to pen poems about it:

But yesterday a naked sod

The dandies sneered from Rotten Row,

And cantered o'er it to and fro:

And see 'tis done!

As though 'twere by a wizard's rod

A blazing arch of lucid glass

Leaps like a fountain from the grass

To meet the sun!(May-Day Ode)

To avoid cutting any trees down, several of Hyde Park's giant elms were enclosed within the building, but this also meant there were birds flying around inside. The organisers were not sure how to rid the building of the birds and avoid any nasty surprises falling down on visitors and exhibits alike. The Duke of Wellington solved the problem when he suggested introducing sparrow hawks into the building.

The Exhibits

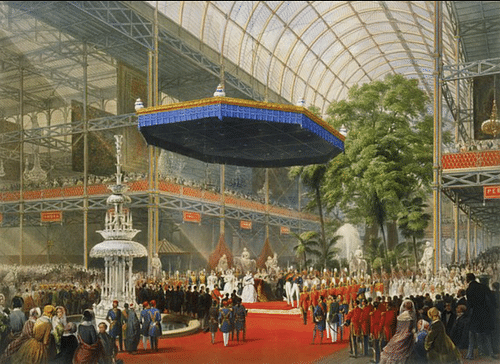

Queen Victoria, with Albert alongside her, officially opened the Great Exhibition in a grand ceremony on 1 May 1851. A full 200-piece orchestra, a choir of 600, and one pipe organ combined to blast out a rousing rendition of the national anthem and the 'Hallelujah' chorus from George Frideric Handel's Messiah. The queen was delighted with what she saw:

It was the greatest day in our history and the triumph of my beloved Albert... It was the happiest, proudest day in my life, and I can think of nothing else, Albert's dearest name immortalized with this great conception... The triumph is immense.

(Phillips, 215)

Tickets to the Crystal Palace wonderland were, at first, terribly expensive at £1 (over £100 or $123 today), but the initial success meant the organisers saw fit to reduce the price after the first month. Still the tickets were not cheap at one shilling each (around £5 or $6 today), but it was a grand day out and well worth a family saving up for. One of the worries of the more snobbish doubters was allowing the general public, particularly the working classes, so close to so many precious and valuable things, but the crowds came and they were respectful and orderly as they took their leisure and admired the spectacle.

The exhibition organisers had no shortage at all of companies and individuals wishing to show their wares. In the end, space limited who could get in. A total of 14,000 exhibitors participated in what was now the greatest show on Earth. Over half of the exhibitors came from Britain, but the United States was well-represented with 500 exhibitors. In all, 34 nations were represented in the exhibition. There was no fee to exhibit, exhibitors had only to meet the cost of getting their works to the Crystal Palace. There were over 100,000 individual exhibits ranging from the easy-to-miss to the gigantic. The exhibits were divided into four broad sections: raw materials, machinery and mechanical inventions, manufactures, and sculpture and plastic art. As the focus of the entire exhibition was on the new and wonderful, art objects were limited to contemporary art with a further restriction that the artist of any particular piece must be living or have died within the last three years. To encourage innovative displays, prizes were given for the best exhibits.

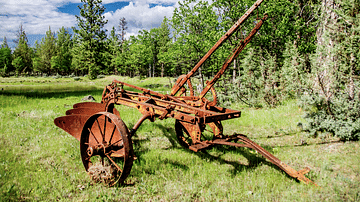

Amongst the larger items on display, there were the very latest steam engines, automated spinning machines, and water pumps. There were scale models of new buildings and bridges, cutting-edge tools, agricultural implements, and weapons like the new mass-produced Colt pistol. There were freezing machines, products made of Indian rubber, fine silks, and examples of the latest set of false teeth. There were cameras which used the brand-new glass negatives. There were telegraphs, still a new invention for many people. The first telegraph line had been set up in Britain in 1838 between London's Paddington and West Dayton Stations. People would have to wait ten more years for the first transcontinental telegraph line.

There was the weird and the wonderful. A 24-ton chunk of coal posed the question of just how it had arrived there. A large fountain splashed not water but perfume. Fashion was well represented with all manner of materials and new designs, including trousers with pockets that the manufacturer promised made them immune to pickpockets, the great petty criminals of the day. There were artworks galore from huge oil paintings to life-size marble statues – the nude ones were controversial and all the more popular for it. Visitors were vowed by the world's largest pearl and the fabulous Koh-i-Noor diamond (worn by Victoria at the grand opening and then placed on permanent display).

For the refreshment of visitors, stalls sold tea, coffee, and soft drinks (but no alcohol). Sandwiches, pies, ice creams, and jellies were on sale, too. Given the mass of humanity descending on Hyde Park, the organisers had been wise enough to provide public conveniences and clever enough to see a commercial opportunity. For the first time, people had to spend a penny to use a public lavatory (and 600,000 pennies rolled into the exhibition's coffers).

Public and press alike were hugely impressed by it all. Word spread that this was a thing to be seen, and soon special trains were laid on to bring in visitors from all over Britain. It was the first time cheap excursion tickets were issued. Employers gave their workers a day off or even two or three to visit the exhibition. Many of the visitors returned multiple times, Queen Victoria herself went almost every day of the five and half months the exhibition ran for. There were many famous visitors, too. The novelist Charlotte Brontë (1816-1855) gave the following description of the experience:

It seems as if only magic could have gathered this mass of wealth from all the ends of the earth – as if none but supernatural hands cold have arranged it thus, with such a blaze and contrast of colours and marvellous power of effect. The multitude filling the great aisles seems ruled and subdued by some invisible influence. Amongst the thirty thousand souls that people it the day I was there not one loud noise was to be heard, not one irregular movement seen; the living tide rolls on quietly, with a deep hum like the sea heard from the distance.

(Dugan, 125)

Success & Legacy

When the Great Exhibition finally closed its doors on 15 October, over 6 million visitors had marvelled at the exhibits, an astonishing one-third of the population of Britain at the time. The exhibition made a profit of £186,000, over £20 million today ($25 million). The money was used to help found the Victoria & Albert Museum in London (then called the South Kensington Museum), which began as a museum of manufacturers but then developed into a hugely impressive collection of fine and decorative arts from around the world. Money from the Great Exhibition also went to the Science Museum, the Museum of Natural History, the Royal College of Music, the Imperial College of Science and Technology, and various other educational institutions. As many of these new museums were built in the Kensington area of London, that quarter became known as 'Albertopolis' in tribute to Albert's achievement.

The architect Joseph Paxton was knighted for his success, and the exhibition was not the end of his fantasy in glass and iron. The Crystal Palace was sold to the London Brighton and South Coast Railway in May 1852, disassembled, and moved to Sydenham in South London where it continued to be used as an exhibition space. Unfortunately, a fire destroyed the building in 1936, and it was never rebuilt. The Crystal Palace had a far-reaching effect on architecture in Britain as after the Great Exhibition a large greenhouse-conservatory became the height of fashion for grander homes.

Finally, the most lasting legacy of the Great Exhibition was that it inspired many successors, variously known as the World's Fair, Universal Exhibition, or EXPO, which are still held regularly around the world. These exhibitions tend now to focus on specific themes such as the e nvironment, but they continue to share the ambition of the Great Exhibition in promoting the collective achievements of humanity and inspiring what might be possible through innovation and mutual understanding across cultures.