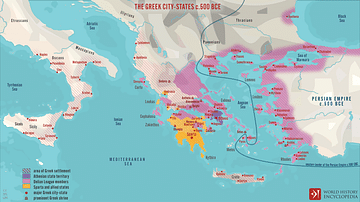

The Greek Archaic Period (c. 800- 479 BCE) started from what can only be termed uncertainty, and ended with the Persians being ejected from Greece for good after the battles of Plataea and Mykale in 479 BCE.

The Archaic Period is preceded by the Greek Dark Age (c.1200- 800 BCE), a period about which little is known for sure, and followed by the Classical Period (c. 510- 323 BCE), which is one of the better documented periods of Greek history, with tragedies, comedies, histories, legal cases and more surviving in the form of literary and epigraphic sources. Each of these periods had its own distinctive cultural identity, yet despite this, there is a certain degree of flexibility with the dates given to the periods. They are modern terms that try to frame various aspects of change in Greek culture which by no means occurred either over one particular year or all together in the same year.

In the Archaic Period there were vast changes in Greek language, society, art, architecture, and politics. These changes occurred due to the increasing population of Greece and its increasing amount trade, which in turn led to colonization and a new age of intellectual ideas, the most important of which (at least to the modern Western World) was Democracy. This would then fuel, in a rather circular way, more cultural changes.

Politics & Law

The politics of Athens underwent a series of serious changes during the archaic period, and the first change was quite possibly for the worse, with the laws of Draco, in around 622/621 BCE (the semi-legendary nature of these laws and its namesake should be noted, and secondly the semi-legendary nature of most occurrences during the first couple of hundred years of the period). As Aristotle says of Draco “there is nothing peculiar in his laws that is worthy of mention, except their severity in imposing heavy punishment” (Politics 2.1274b).

The legacy of their infamy (loans could be made on the security of one's own person), still exists in the modern word 'draconian'. Most brutal of all however were the death penalties; Plutarch relates that “it is said that Draco himself, when asked why he had fixed the punishment of death for most offences, answered that he considered these lesser crimes to deserve it, and he had no greater punishment for more important ones”. Whilst Aristotle comments that there was nothing particular about the laws, what is important is that the laws, for the first time in Athens, were written down for all to see, and to read (for those who were literate).

The next major changes that came were brought about by Solon (c. 594 BCE), whose historical authenticity is more certain than Draco's due to fragments of his poetry that Plutarch relates as still existing in his time. His changes to Athenian law were the first to give the lower classes a fairer chance — however, the positions of power were still only available to those of wealth. It was the effects of class inequality that Solon tackled, not the causes of them. The most notable change implemented by Solon was the seisachtheia, the 'shaking-off-of-burdens'. This decree cancelled debts, banned the use of one's own person as security for a loan, and recalled all of those who had been sold as slaves and those who had fled to escape such a fate.

There were also Solon's reforms of weights and measures, the right of third party appeal was introduced among other developments. In order that he might not be pressured into changing these laws, Solon left Athens for ten years (according to Herodotus) and went to Egypt where he wrote political poems.

It was only after Solon that a sense of self-conscious democracy in Athens began to develop; a development that could be seen as either a social phenomenon or a political and institutional phenomenon. The changes then came thick and fast. The age of tyrants that had started with Draco would soon nearly be over, but not if the Peisistratids had anything to do with it.

The Peisistratids were a short line of Athenian tyrants that started with Peisistratos, and it should be noted that the term 'tyrant' during this period did not have the negative connotations that it has today. In fact, Peisistratos was no draconian ruler, but one who felt a certain amount of sympathy with the poorer classes of Athens. Aristotle gives a good account of the events that follow. After Pesistratos' death his sons Hippias and Hipparchus held the tyranny until an assassination plot was launched against them by Harmodias and Aristogen.

Cleisthenes came to power in the political gap that was left after the tyrannicides and is famous for introducing isonomia (equal laws) in Athens. He achieved this through various reforms which meant that less importance was given to aristocratic background. The biggest reform that Cleisthenes made was to the tribal system of Athens. Previous to his reform there had been four tribes (based on family ties), Cleisthenes changed this to ten tribes, each formed by a slightly complicated subsystem.

The tribes were formed by a collection of demes (similar to an English Parish; small localities of residence) which were themselves placed into one of thirty trittyes, 'thirds' (three per tribe); a deme would be in either one of three regions depending on its location: the coast, the city, or the inland. The trittyes therefore were an amalgamation of ten demes from each of the three regions; each tribe therefore had three trittyes in it, one composed of demes from the city, one with demes from the coast, and one of demes from inland. Further to this Athenians would no longer take their 'surname' from their father, but from their deme. This all meant that the family ties, traditions and allegiances that had caused prior political friction (and had led in some way to the Peisistraid tyrannies) had been broken up. It was also during Cleisthenes' time that many Athenian official positions began to be selected by lot. Aristotle and Herodotus cover these events in quite good detail.

Art & Architecture

The art and architecture of the Archaic Period also underwent various overhauls; the earlier geometric style was replaced with an orientalising style, which in turn was replaced by black figure pottery. Black figure pottery was first starting to be used in Corinth c. 700s BCE, but the first signed example dates to c. 570 BCE, when attic black figure pottery was in its heyday (c. 630- 480 BCE) and is of Sophilos. As this technique was further developed and explored, it gave way to Red Figure pottery, which started to develop c. 530 BCE.

It was also during this period that many changes and developments were made to temple building. The first phase of the Heraion at Samos was built in the mid. 8th C. BCE, yet its final, unfinished, reincarnation wasn't begun until c. 530 BCE. Many changes had occurred by then. The Heraion at Olympia, built c. 600 BCE, was the first temple to have a stone stylobate and lower wall course, but was still built with wooden columns, one of which still survived to Pausanias day. Today the remnants of this development can be seen in the varying sizes and styles of the temple's Doric stone columns since they were created by different hands in different times in order to replace wooden columns as needed.

The Corcyra Artemision (c. 580/ 70 BCE) was the first Greek temple to have a stone entablature and the Temple of Apollo (c. 580-550 BCE) at Syracuse is now known as the Cathedral of Syracuse, being the longest continually lasting single building to remain consecrated ground, in this case, since its Archaic origins. The age of tyrants can also be witnessed in one particular temple, in this case, not relating to Athens' tyrants, but to Samos', namely Polykrates (c.540- 520 BCE) who commissioned the fourth stage Heraion at Samos. Greece's developing international realtionships can be witnessesed in this was too, with King Croeus dedicating a column of the Temple of Artemis and Ephesus; and it still bears his mark to this day.

Panhellenic Games

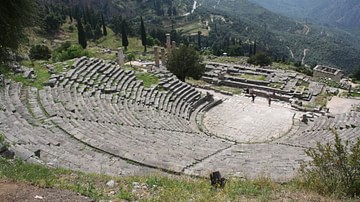

It was during the Archaic period that the four major panhellenic games of Greece were founded. In 776 BCE the Olympic games were traditionally begun by Hercules and Pelops (and their influence can be seen in the sculptural decoration of the classical Temple of Zeus there), whilst at Delphi athletic games had taken place from c. 586 BCE, the home of the Pythian games, and the panhellenic Isthmian games were founded at Corinth c. 581 BCE. The last of the 'big four' was founded c. 573 BCE, and this was the Nemean games.

However, in the normal Archaic tradition, each of these games was surrounded by its own foundation myth, not just the Olympics. The Pythian games, which had originally been solely a games of music and dance, were supposedly founded by Apollo himself (according to Pindar), the Isthmian games (according to Pausanias) by the legendary King of Corinth, Sisyphus, and the Nemean Games after Hercules had slain the Nemean lion. But when we think of victory at the games, there is one name that jumps out, and it isn't that of a victor, but of a poet, Pindar, who was composing between c. 500- 446 BCE, writing his Pythian odes and others in honour of the various victors at the games.

Alphabet & Literature

From Homer and Hesiod, through to Pindar and Aeschylus, the Archaic Period underwent a vast development in the field of Greek literature, and language too, with the first Greek alphabet being developed. The Greek alphabet developed out of the Phoneician alphabet, and is in itself a tribute to the increase in trade and exploration in the period that made this cultural exchange possible: the earliest Greek writing being dated to c. 750 BCE. However, despite the development of the Greek alphabet, the oral tradition of poetic composition and transmission was still the method used by Hesiod and Homer; it wasn't until c. 670 BCE and the rule of Peisistratus that a definitive version of the Iliad and Odyssey was attempted.

The end of the Archaic period also had a literature that is just as influential, less well known perhaps, but it set the stage for the later classical tragedians and comedians. 535 BCE was the year of the first dramatic festival in Athens and in 485 BCE comedy was added, and one year later Aeschylus had won his first dramatic competition in Athens, but it wasn't until 472 BCE that Aeschylus' Persians was composed.

Persian Wars

The Persian Wars, perhaps the most influential set of events in the Archaic period, which couldn't possibly be given justice to here, started with the Ionian revolt of Greek colonies and settlements in Asia Minor from the Persian Empire which prompted Darius I's retaliation to invade Greece, which failed at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE. This was later avenged by the second invasion of Greece by Xerxes, who was finally expelled with the combined victories at Plataea and Mykale, though only after the equally as famous battles of Thermopylae and Salamis. Salamis was won by the fleet that Themistocles had persuaded the Athenians to build from the silver mines at Laurium, and this silver would continue to be vitally important into the Classical Period.

However, there were loses in these wars; the sacking of the Athenian acropolis and Agora, the death of Leonidas, and in the end, the freedom of the Ionic tributaries to Athens as the Delian League soon became the Athenian League. The change being that in the Archaic period there was war with Persia, in the Classical period, diplomacy.

The Archaic Period is, therefore, a highly important time period in its own right, but is also highly important in putting the events of the Classical Period into context. However, this definition only covers some of the many events and developments, and covers some of them only briefly: the Archaic Period is perhaps the richest and most complicated in Greek history.