Gula (also known as Ninkarrak) is the Sumerian goddess of healing and patroness of doctors, healing arts, and medical practices. She is first attested to in the Ur III Period (2047-1750 BCE) where she is referenced as a great goddess of health and well-being. She was among the most popular deities of ancient Mesopotamia.

Her name (Gula) means 'Great' and is usually interpreted to mean 'great in healing' while Ninkarrak means 'Lady of Kar,' interpreted as 'Lady of the Wall,' as in a protective barrier, though it has also been taken to mean 'Lady of Karrak,' a city associated with that of Isin.

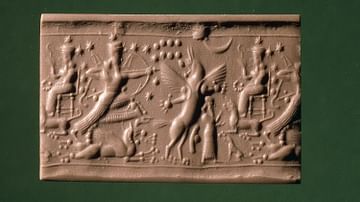

In Sumeria, she was referred to as 'great physician of the black-headed ones' (the Sumerians). She is commonly referred to in Mesopotamian medical texts and incantations as belet balati, 'Lady of Health,' and as Azugallatu, 'Great Healer.' Her main cult center was at Isin, though her worship would spread across Sumer in the south upwards to Akkad and, eventually, throughout the entire region of Mesopotamia. Her iconography depicts her always with a dog, sometimes seated, and surrounded by stars. She is associated with the underworld and transformation.

Originally Gula was a Sumerian deity known as Bau (or Baba), goddess of dogs. People noticed that when dogs licked their sores, they seemed to heal faster, and so dogs became associated with healing and Bau transformed into a healing deity. When her worship spread from the city of Lagash to Isin, she became known as Ninisina ('Lady of Isin'). Her other names included Nintinugga and Nimdindug, which related to her healing talents, or still others which simply elevated her to patroness of a city.

Scholar Jeremy Black notes that many of her names were "originally the names of other goddesses [such as Meme]" whom she assimilated (101). When she was venerated in Nippur, she was known as Ninnibru, 'Queen of Nippur,' and associated with the hero-god Ninurta. She became known as Gula, the great healer, during the latter part of the Old Babylonian Period (2000-1600 BCE) and is best known by this name in the present day.

Mythological Origin & Family

She was the daughter of the great god Anu, created with his other children at the beginning of time, and her husbands/consorts are variously given as Ninurta, the healer god, and divine judge Pabilsag, or the agricultural god Abu. Scholar Stephen Bertman writes, "Because at least two of these divinities were connected with agriculture, her marriage to them may symbolically reflect the medicinal use of plants" (119). Her sons were Damu and Ninazu, and her daughter Gunurra, all healing deities.

Damu was the central Sumerian god of healing who combined the magical and 'scientific' approaches to disease. He was associated with the dying and reviving god figure Tammuz (also known as Dumuzi) central to the tales involving Inanna and rebirth; hence he is also associated with transformation and transition. He is frequently mentioned with Gula in incantations for healing. Although Gula was considered the supreme healer, Damu was thought to be the intermediary through which her power reached doctors.

Ninazu, who was associated with serpents (symbols of transformation), the underworld (transition), and healing (transformation), carried a staff intertwined with serpents. This symbol was adopted by the Egyptians for Heka, their god of magic and medicine, and then by the Greeks as the caduceus, the staff carried by Hermes Trismegistus, their god of magic, healing, and writing (associated with the Egyptian god Thoth). Today, of course, the caduceus is seen in doctor's offices and medical practices around the world as the symbol of Hippocrates, the father of medicine.

Doctors in Mesopotamia

There were two types of doctors in ancient Mesopotamia: the Asu (a medical doctor who treated illness 'scientifically') and the Asipu (a healer who relied upon what modern people would call 'magic'). There were also surgeons and veterinarians who could come from either of these backgrounds. Dentistry was practiced by both kinds of doctors and both may have also presided at births.

It is certain that midwives (sabsutu) delivered the child, not the doctor, and yet the doctor was paid a fee for providing some kind of service at births, since records make it clear that they were paid more for the birth of a male child than a female. It is possible that the Asipu could have recited prayers to the gods or chants to ward off demons (most notably the demon Lamashtu who killed or carried off infants) or that the Asu could have eased labor pains with herbs but not assisted with the actual birth.

A pregnant woman and one who was in labor wore special amulets to protect her unborn child from Lamashtu and to invoke the protection of another demon, Pazuzu. Demon did not always carry the connotation of evil that it does in the modern day, and could be a benevolent spirit though, in Pazuzu's case, he was so malevolent he was invoked to scare away other dark entities. Although modern-day scholarship sometimes refers to the Asipu as a 'witch doctor' and the Asu as a 'medical practitioner,' the Mesopotamians regarded the two with equal respect. Scholar Robert D. Biggs notes:

There is no hint in the ancient texts that one approach was more legitimate than the other. In fact, the two types of healers seem to have had equal legitimacy, to judge from such phrases as, 'if neither medicine nor magic brings about a cure,' which occur a number of times in the medical texts. (1)

The significant difference between the two types was that the Asipu relied more explicitly on the supernatural, while the Asu dealt more directly with the physical symptoms the patient presented with. Both types of healers would have accepted a supernatural source for illness, however, and the Asu should not be considered more 'modern' or 'scientific' than the Asipu.

These doctors operated out of the temples and treated patients there but more frequently made house calls. The city of Isin, as cult center for Gula, is thought to have served as a training center for physicians, who were then sent to temples in various cities as needed. There is no evidence of private practice per se, although kings and the more affluent had their own physicians. The doctor was always associated with some temple complex.

Women and men could both be doctors, though, as scholar Jean Bottero notes, "Women scribes or copyists, exorcists or experts in deductive divination [the Asipu and Asu] could be counted on the fingers of one hand" (117). Still, there were more female physicians in Sumer than elsewhere, and it was no accident that it was the Sumerians, with their high regard for women, who first envisioned a female deity of healing.

Illness & the Gods

Illness and disease were thought to come from the gods as a punishment or a wake-up call to the individual. The gods had created human beings as their co-workers and so cared for them and provided for their happiness. Even so, as Bottero points out, humans had a tendency toward sin and sometimes needed correction in the form of illness or affliction to turn them back to the right path. Sickness might have other supernatural causes, however, such as demons, evil spirits, or the angry dead. It was entirely possible for an innocent to fall sick, through no fault of their own, and for the doctors to perform every incantation correctly and apply the proper medicines, and yet that person still die.

Even if one god intended only the best for the sick person, another god could have been offended and would refuse to be placated, no matter what offerings were made. To further complicate the situation, one also had to consider that it was not the gods causing the problem but, instead, a ghost whom the gods allowed to cause the trouble to rectify some wrong, or simply an evil spirit, demon, or an angry ghost. Ghosts in ancient Mesopotamia were recognized as a potential threat to one's safety and security to be recognized just like any other. Biggs writes:

The dead – especially dead relatives – might also trouble the living, particularly if family obligations to supply offerings to the dead were neglected. Especially likely to return to trouble the living were ghosts of persons who died unnatural deaths or who were not properly buried - for example, death by drowning or death on a battlefield. (4)

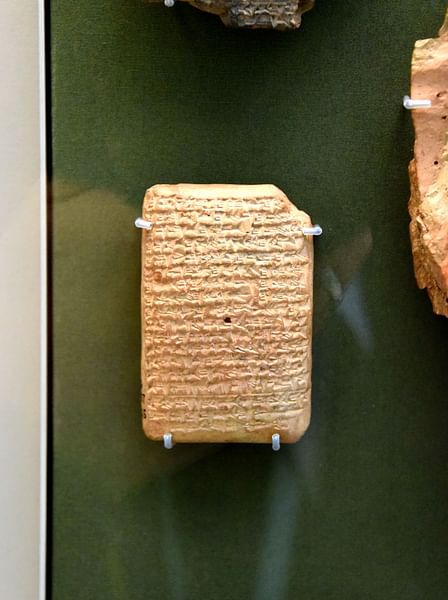

Medical books from the library of Ashurbanipal make it clear, however, that doctors had an impressive amount of medical knowledge and applied this regularly in caring for their patients and appeasing the gods and the spirits of the dead. This knowledge, it was thought, came from Gula as a gift from the gods. In the same way that they had sent the affliction, for whatever reason, they also provided the means for a cure.

Gula was frequently called upon for help in conception, especially when it was thought some supernatural entity was interfering, and appears in inscriptions invoking fertility. Whether the disease was caused by a god, ghost, or evil spirit, the healing powers of Gula could usually restore the patient to health. She was not always so kind and solicitous, however, and was just as well known for her violent temper.

Gula as Punisher & Protectress

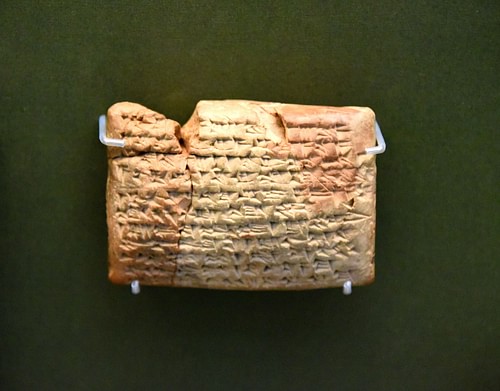

The goddess is almost as frequently invoked in curses as she is in healing. She was thought to be able to bring earthquakes and storms when she was angered, and among her epithets is 'Queen of the Tempest' and 'She Who Makes Heaven Tremble.' A tablet from the reign of Nebuchadnezzar I (1125-1104 BCE) invokes Gula as a protectress for a memorial. It was customary, whenever a king erected a monument, to add a curse to the inscription on anyone who would deface or remove it, calling upon the gods to punish the transgressor in all kinds of ways.

The inscription on Nebuchadnezzar I's memorial reads in part how, if anyone should deface or remove it, "May Ninurta, the king of heaven and earth, and Gula, the bride of E-Sharra, destroy his landmark and blot out his seed" (Wallis Budge, 126). She is also mentioned in other inscriptions in the same way.

People thought to appease her through worship at her temples where dogs roamed freely about and were well cared for as her sacred companions. Bertman writes:

Her sacred animal was the dog and ceramic models of dogs were dedicated to her at her sanctuaries by those who had been blessed by her tender mercies. (119)

The famous Nimrud Dogs, ceramic statuettes found in the 1950's at the city of Nimrud, are among the best-known examples of amuletic figures dedicated to Gula.

Her healing powers were as greatly respected as her temper was feared, and her other epithets include 'Healer of the Land,' 'She Who Makes the Broken Whole Again' and 'The Lady Who Restores Life.' It was Gula, after the Great Flood, who is said to have breathed life into the new creatures made by the gods to animate them. Through this act, and her care for humans afterwards, she was considered a kind of Mother Goddess, along the same lines as Ninhursag who actually created the bodies of human beings.

Worship at Gula's temples, shrines, and sanctuaries would have been the same as that of any Mesopotamian god or goddess: the priests and priestesses of the temple complex would have taken care of her statue and inner sanctum, and the people would have paid their respects in the outer courtyards, where they would have met with the clergy, had their needs addressed, and left their gifts of supplication or thanks. There were no temple services such as one would recognize in the modern day.

One significant difference between rites at her temples and at those of other deities was the dogs who somehow took part in the healing rituals, though precise details of what they did are unclear. They may have played a part in ritual sacrifice as there were over thirty dogs buried beneath the ramp leading to Gula's temple at Isin. These dogs may have simply been temple dogs, however, who were honored with burial at the entrance.

Ceramic figures like the Nimrud Dogs were buried at doorways and thresholds, often inscribed with Gula's name, for protection against harm. These figurines have been found at a number of sites besides Nimrud, most notably at Nineveh, and inscriptions make clear that burying dog figures - or in this case actual dogs - was a powerful charm in protecting a home from evil.

Female deities lost much of their prestige during the reign of Hammurabi (1792-1750 BCE) and afterwards when male gods dominated the theological landscape, but Gula continued to be worshiped in the same way and with the same respect. Her transformative powers associated her with agriculture (another of her epithets is 'Herb Grower'), and so she was worshiped in hopes of a good harvest, as well as for childbearing and good health in general.

Veneration of the goddess continued well into the Christian period, and in the Near East, she was as popular as many better-known deities such as Anahita or Isis. Her cult declined as Christianity became more entrenched in the minds of the people until, by the end of the first millennium CE, she had been forgotten.