The play Agamemnon was written by one of the greatest Greek tragedians Aeschylus (c. 525 – 455 BCE), “Father of Greek Tragedy.” Older than both Sophocles and Euripides, he was the most popular and influential of all tragedians of his era. Winning first prize at the Dionysia competition in 458 BCE, Agamemnon was the first play in a trilogy The Oresteia; the remaining two tragedies were Libation Bearers (Choephoroi) and Eumenides. As was common in many of the competitions, there was also a satyr play, the lost Proteus.

In Agamemnon, the Greek king of Argos and commander of the forces against King Priam's Troy has returned victorious after ten grueling years. With him is his newly acquired concubine, the beautiful prophetess Cassandra, daughter of King Priam and a priestess at the shrine of Apollo. In his absence, his “devoted” wife Clytemnestra has taken a lover Aegisthus, Agamemnon's first cousin. The scheming couple, hoping to rule Argos together, decides to kill the returning king and his mistress. The remaining two plays of the trilogy - the only one to survive intact - are concerned with the revenge of the son Orestes and his trial in Athens.

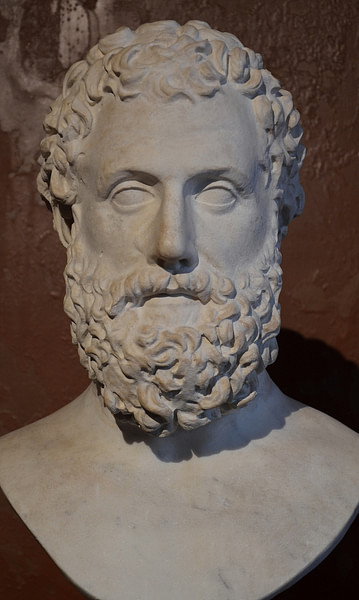

Aeschylus

Aeschylus was from an aristocratic Greek family of Eleusis, an area west of Athens. Profoundly religious and a strong proponent of Athenian democracy, he fought at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE where his brother was killed. He may have also fought at the Battle of Salamis in 480 BCE. He began producing plays in the 490s BCE, winning his first victory in 484 BCE. Of his over 90 plays, only six have survived; the authorship of a seventh, Prometheus Bound, is in question. His trilogy Oresteia won a first at Dionysia in 458 BCE. Eventually, he won a total of 13 first-place victories, second only to Sophocles. While little is known of his wife and family, his sons Euphorion and Euaion were also playwrights. Somewhat radical in politics and religion, his plays often contain strong political themes.

In her book The Greek Way, author Edith Hamilton said, “He knew life as only the greatest poets can know it. He perceived the mystery of suffering” (182). Although he lived most of his life in Athens, he was invited to Syracuse by King Hieron. Continuing to write until the end of his life, he would die there in 455 BCE. According to the editors of Aeschylus II, Aeschylus played a major role in “developing tragedy to its pinnacle of dramatic sophistication and moral power.” (Grene, 2) Prior to Aeschylus, a play's dialogue was hampered with only one actor. With his introduction of a second actor, plot construction was given more freedom. Afterwards, the intricacy of plays increased. Unlike other playwrights, Aeschylus also designed costumes, trained his choruses, and may have even acted in some of his own plays.

The myth

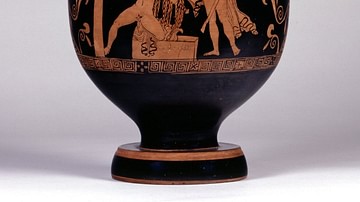

As with many of the Greek tragedies, the audience was well aware of the myths surrounding the play. In this instance, the stories of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey are the prelude to Aeschylus's trilogy. The ten-year war is finally over and the conquering heroes are sailing home, Menelaus and his wife Helen to Sparta (they would get delayed), Odysseus to Ithaca, and Agamemnon to Argos. However, this time, in Aeschylus's version, the returning Agamemnon appears to be a less than the contemptible character of Homer while his long-suffering wife comes across as a villain compelled by jealousy and hatred to seek revenge. Her contempt for her husband dates back a decade to his departure to Troy. The goddess Artemis stilled the winds, denying the Greek fleet the ability to sail. Having been offended by the arrogant king, she demanded the sacrifice of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra's eldest daughter Iphigenia. With her sacrifice, the winds stirred and the fleet sailed.

Her lover, Aegisthus, was not without just cause for his revenge. The two cousins were members of a cursed family. Although versions of the story vary, their fathers, Atreus and Thyestes, had squabbled over both a throne and an inheritance. In an act of spite, Thyestes seduced the wife of Atreus. After learning of his wife's adultery, Atreus invited Thyestes to a dinner, where after killing his two nephews he served his unsuspecting brother the young boys cooked in a stew. In an act of rage, Thyestes cursed the descendants of Atreus, the brothers Agamemnon and Menelaus. The two descendants would one day become kings of Argos and Sparta, respectively. Aegisthus was the third, and only, surviving son of Thyestes. So, add together the horrible sacrificial death of Iphigenia, the curse of Thyestes, and the presence of the concubine Cassandra, and one might understand why the grieving Clytemnestra and her lover chose to kill Agamemnon as well as Cassandra and rule Argos together.

Cast of characters

Agamemnon has a small cast:

- Clytemnestra

- Agamemnon

- Cassandra

- Aegisthus

- a watchman

- a herald

- and a chorus of old men of Argos

The Plot

The play takes place outside the palace of Agamemnon in Argos. A watchman gazes out from the roof of the palace; a chore he has been performing for over a year, hoping for the safe return of his king. Suddenly, there appears in the distance a beacon. He calls out for his queen Clytemnestra. A chorus of twelve elders enters:

Ten years since the two kings, Menelaus and Agamemnon, great sons of Atreus, claimed justice from Priam, and in the double name of throne and scepter, by the grace of Zeus, from this land launched warships… (Grene, 46)

The old men turn towards the palace doors waiting for their queen to appear, anxious for her to tell them what news she has heard. They plead for her to “… be the healer of worry that foreboding darken even as hope flares from each sacrificial fire…” (48). Clytemnestra finally makes her long-awaited appearance:

May good news only, as the saying goes, be born with the dawn that's born from mother Night. The joy I have to tell you outruns all hope. The city of Priam is in Argive hands. (54)

While they are elated to hear of the good news, the chorus is confused; they question her: when was it taken, how could she have learned of it so quickly. Her answer is simple; it came beacon to beacon. Soon, a herald arrives and announces his joy to the chorus at arriving home safely, thanking Apollo, his healer and protector. He announces that Agamemnon has also arrived home. Having heard the good news, the queen reenters from the palace. She declares that she is ready to greet her husband and hear the whole story of Troy's capture, thanking the gods for his safe return.

The chorus asks the herald of Menelaus's whereabouts, whether he left before or after the herald. The herald replies that the king's ships disappeared into the distance and everyone hopes for his safe return and by the will of Zeus he will arrive home safely. Shortly after the herald exits, Agamemnon arrives in a cart, accompanied by the daughter of King Priam, Cassandra. The king speaks to the chorus:

I first greet Argos, as is only just, and all the gods who dwell in the land, they who have helped me in my safe return and in the justice I at last exacted from Priam's city. (72)

He speaks of the Trojan horse, “the wooden monster that the Argive host till they made their fierce leap when the Pleiads set” (72). He even pays homage to Odysseus, telling the crowd that he deserves their praise and thanks.

The queen expresses to the chorus how much she loves her husband, how sad her life had been since he sailed to Troy, and how difficult it was for a woman, with her husband gone. She even had thoughts of suicide were it not for those who loosened the rope from around her neck. While Agamemnon appreciates her praise, he believes that it should come from others not her; she should not treat him like a barbarian or coddle him like a woman. She replies that a life unenvied is an unenviable life. Agamemnon concedes to her wishes; he and the queen enter the palace together with his final words asking that Cassandra be treated well.

Soon Clytemnestra reappears briefly and tells Cassandra to go into the palace and “share the lustral waters of our house” (74). In a feeble attempt to console the captive, she adds that “even Heracles they say, was once sold into slavery and had to stomach the gruel all slaves must eat” (74). She exits into the house. Cassandra cries out for Apollo, her destroyer. She asks aloud where the king has brought her. The chorus leader tells her it is to the house of Atreus. She tells them that it is a house that hates the gods, a slaughterhouse with a floor drenched in blood. She speaks of the past and the sins of the two brothers, the father and the uncle of Agamemnon. Then she speaks of prophecies, warnings of the death of their king:

The children are waiting for their own slaughter, for the flesh their uncle roasted, and their father ate it. ... Keep the bull away from the cow. She has caught him in the robes, and with the slick device of her black horn strikes, and he slumps in the roiling water. (82-83)

Cassandra cries out that she also sees her own death. She tells the chorus that she is cursed because her prophecies can never be believed. She had seen the fall of Troy, but her warnings were unheeded. The chorus leader tells her to be quiet. However, she says, “I say you'll look on Agamemnon butchered” (87). She tells them that as they pray, the king is being killed. She speaks of a co-conspirator (Aegisthus) who will be the cause of her death. As she speaks she tears off her priestly robes. She tells the chorus that her death will be avenged:

… there will come, in turn, another to avenge us, a son who will slay his mother, respite his father, an exile and a wanderer, hounded far from this land, he will return to put the capstone on the killing of his kin. (89)

This, of course, is a reference to Orestes, the son, who will soon return and kill his mother and his lover. As Cassandra enters the palace she recoils and speaks of the “stench of slaughter” (90). She enters the palace, knowing she is about to meet her own death. Cries are heard from inside the palace. Agamemnon yells aloud; he has been struck.

When the palace doors open, the queen stands over the corpses of Agamemnon and Cassandra. This was not a sudden act of revenge. She had been brooding some time. She attempts to tell the chorus why she sought vengeance, reminding them that no one objected when her husband killed their child “to charm the winds of Thrace.”(94) She still weeps for her daughter Iphigenia, the daughter she will meet in the afterlife. The chorus charges that she will pay for her crimes, but she then reminds them of the crimes of his family:

This is Agamemnon, my husband, now a corpse, the work of this right hand, a righteous workman. There's nothing more to say. (94)

From the side Aegisthus enters with a group of armed men, yelling how the gods “are avengers of mankind” (100). He looks at the body of Agamemnon and says the king has paid for the crimes of his father. He speaks of his father Thyestes and how he had been served his own children at a feast. He claims that he was the one who planned the murder, planned it with justice,

for he drove us out, my wretched father and myself, his third born, still just a swaddled babe. But when I grew to manhood, Justice brought me back again, and from afar I carefully laid my hand upon this man, stitching piece by fatal piece, the cloth of this plan. (100-101)

The chorus is outraged. He gives orders for his men to charge the crowd, but Clytemnestra stops him by saying:

There's been enough destruction, let's have no more bloodshed. ... Ignore this harmless barkings, you and I will rule the house, and set it all in order. (103)

Analysis

The major theme of the play centers on the concept of justice. The Argos queen Clytemnestra deems the cold-blooded killing of her husband Agamemnon and his concubine Cassandra is justified. He had sacrificed their eldest daughter Iphigenia to the goddess Artemis so his ships could sail to Troy to retrieve the wife of his brother Menelaus. When he returns after an absence of ten years, he brings with him a concubine, Cassandra, the daughter of the fallen King Priam. As her husband's approaches, the queen feigns loyalty and devotion as she voices her faithfulness to her husband. She even speaks of how she cried during his absence. The queen's lover (and her husband's cousin) is also not without justification for his part in the murder, a murder he claims to have planned. He seeks revenge for the exile of his father who had been served his own sons cooked in a stew prepared by Agamemnon's father.

In his book Greek Drama, Moses Hadas states that the true tragedy of the play revolves around both war and politics. Hadas emphasizes that other “crimes” occurred before the play begins. The Trojan prince Paris had abducted Menelaus' wife Helen (a woman considered by Hadas to be evil) which led to the Trojan War that brought about the death of countless Argives. Although he had sacrificed his daughter for a senseless war and led Argive men to their death, the chorus of old men remains loyal to their king. This is seen at the end of the play when the chorus stands in contempt of the queen as she states her plans to rule Argos with Aegisthus. Hadas sees Clytemnestra as a woman who murders without real justification. She rationalizes her hatred because of the loss of her daughter and the presence of Cassandra. She believes herself to be an “instrument of fate” (16). This concept of justice reappears in the remaining two plays of Aeschylus' trilogy. In the second play Orestes, the son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, seeks revenge (justice) for the murder of his father at the hands of his mother and Aegisthus.