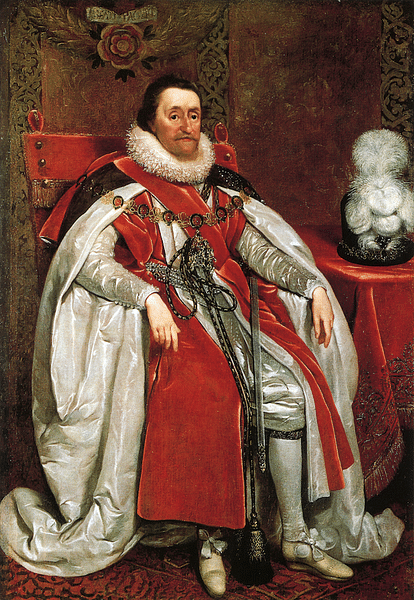

James I of England (r. 1603-1625), who was also James VI of Scotland (r. 1567-1625), was the son of Mary, Queen of Scots, and he unified the thrones of Scotland and England following the death of Queen Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603) who left no heir. For the first time, there was a single monarch for England, Scotland and Ireland.

The king’s eventful reign witnessed the adoption of the Union Jack flag in 1606, the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605, publication of the Authorised Version of the Bible in 1611, and the voyage of the Mayflower to North America in 1620. James was convinced of his divine right to absolute power and this, along with his high-spending, brought him into frequent conflict with the English Parliament. A member of the royal house of Stuart, James would reign until his death in 1625; he was succeeded by his son Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649).

Family & Reign in Scotland

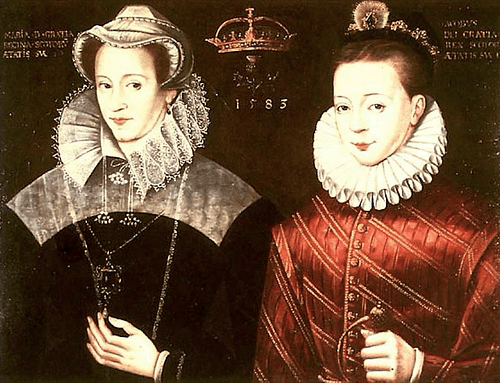

James was born in Edinburgh Castle on 19 June 1566; his father was Henry Stewart, Lord Darnley (1545-1567), and his mother was Mary, Queen of Scots (r. 1542-1567). Mary’s reign was far from smooth with scandals from two marriages and two murder plots, including one which led to the death of Lord Darnley in February 1567. Mary was in no way helped by her steadfast promotion of Catholicism in a kingdom which had shifted markedly towards Protestantism. In short, Mary was obliged to abdicate on 24 July 1567 in favour of her son, who became James VI of Scotland. James was crowned on 29 July 1567 in the church of the Holy Rude in Stirling. James was barely one year old, and so, given a Protestant education, he could be easily manipulated by the barons who ruled in his name, a situation which saw four successive regents before James reached adulthood.

In 1578, the government led by the regent the Earl of Morton (in office since 1572) was dissolved and James began to rule in his own right, at least nominally since he was still only 12 years old. Unfortunately, this did not last long and James Stewart, the Earl of Moray (l. 1531-1570) took over the kingdom as regent. The young king became a pawn in the religious battleground of Britain where French Catholic monarchs supported Catholics in Scotland, and England’s Protestant queen, Elizabeth I, supported followers of her faith across the border. James was even abducted by Protestant English lords in August 1582, an event known as the Raid of Ruthven after its ringleader William Ruthven, Earl of Gowrie. In the process, the Earl of Moray was driven out of Scotland. The takeover was short-lived, though, and the king was released after 10 months, and the Earl of Moray was back in power again from June 1583. Ruthven was hanged. Meanwhile, the English Protestant conspirators did not give up, and supported by an ever-more Protestant population, by October 1585 the Catholic cause was finally dead in Scotland. A peace treaty, the Treaty of Berwick, was signed between England and Scotland in July 1586. James himself seems to have been keen for peace and sided with neither religious side.

On 23 November 1589, James married Anne of Denmark (b. 1574), the daughter of Frederick II of Denmark and Norway (r. 1559-1588). This union was a good way to strengthen the important commercial ties between Scotland and the Baltic states. Anne died in March 1619, but the couple had seven children, only three of whom survived infancy: Henry (b. 1594), Elizabeth (b. 1596), and Charles (b. 1600). Unfortunately, Henry died of typhoid fever in 1612; he was only 18 and so the less-promising Charles became heir to the throne. Elizabeth, meanwhile, went on to marry the King of Bohemia, and her grandson would rule England as George I of England (r. 1714-1727), the first of the Hanoverian Dynasty.

James’ reign in Scotland settled down as he pursued a middle way and tried to keep Catholics and Protestants content and free from persecution. Significantly for later events, the king wrote his The True Law of Free Monarchies (1598) and Basilikon Doron (1599), both of which strongly supported the idea of the divine right of kings - that monarchs were only accountable to God and could not be removed from office. James was a keen scholar and writer, and he also worked on poems, ecclesiastical commentaries, a translation of the Book of Psalms, and treatises against witchcraft and smoking.

Over the 1590s, there were squabbles with the king’s most powerful nobles, but no significant challenge came to his rule, and 1598 finally saw the nobility acquiesce to royal justice in matters of dispute between themselves. The one bone of contention remained the cost and increasing debt of the royal purse, but this was about to be solved by James shifting his entire court to London.

Succession to the English Crown

Mary, Queen of Scots had fled Scotland for England and protection from her cousin Elizabeth I. The English queen, though, did not trust her cousin and, as it turned out, was perhaps justified as during her 19-year confinement in various English country houses, Mary was found guilty of plotting treason against Elizabeth and conspiring with the Spanish Crown. Mary was executed on 8 February 1587. James made a formal complaint to Elizabeth concerning the death of his mother but did no more than that, and his attempts to have himself nominated as Elizabeth’s heir came to nothing. Given a handsome annual payoff and content enough to remain king and at peace with England, James bided his time and pursued his great passion for hunting. Perhaps crucially, England would presently have its hands full with a full-on Spanish invasion: the Spanish Armada fleet of 1588.

Elizabeth's navy saw off the Spanish Armada, and her throne remained secure. However, with no children and not having nominated an heir, when Elizabeth died on 24 March 1603, a succession crisis began. As her closest relative, James was invited to become the next king of England as James I. He did have English royal blood in his veins, for James was the great-great-grandson of Henry VII of England (r. 1485-1509). Consequently, it was the end of the House of Tudor and the beginning of the House of Stuart in England (James' mother Mary had changed the spelling from Stewart). There seems to have been very little opposition to James as first choice, and it may be that Elizabeth nominated him as her heir on her deathbed, although scholars do not agree on this point. Certainly, Elizabeth’s most important councillors supported James.

James was crowned the King of England and Ireland on 25 July 1603 at Westminster Abbey, he was, then, the first monarch to rule over England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland together. Following a proclamation on 20 October, James styled himself as the ‘King of Great Britain’. As a final touch indicating a new order had begun, James moved his mother's remains from Peterborough to a magnificent new tomb in Westminster Abbey. He now settled down to his new court in England, and he would only once, in 1617, ever return to Scotland. The governing institutions north of the border remained as they were before, and James governed through the Privy Council and Scottish Parliament via correspondence, as he put it himself, he governed by the pen, not the sword.

There seems to have been no objection from the ordinary people of England to the change of ruling dynasty, and the new king had even been cheered in his procession to London. One small group of English nobles did take exception, though. This group of rebels was led by Sir Walter Raleigh (c. 1552-1618) and Lord Cobham, and their aim was to put James’ cousin Lady Arabella Stuart on the throne. The ringleaders were arrested and the plot came to nothing.

European Affairs

The accession of a Scottish king finally ended the cross-border raiding that had been going on for centuries between northern England and southern Scotland. James' reign also saw the end of the costly and unpopular war with Spain that had blighted Elizabeth's reign. A peace treaty was signed by both countries in London on 18 August 1604. Relations with France were peaceful, but there was not much respect for the uncouth Scottish monarch. Henry IV of France (r. 1589-1610) once described James as "the wisest fool in Christendom" (Philips, 140) over the seeming paradox of a king with no tact or manners who still seemed to manage his own position as monarch well enough. James’s son Charles at least gained greater favour in French eyes, and a marriage was arranged for him in 1624 to Henrietta Maria, the young sister of the new king, Louis XIII of France (1610-1643). In Ireland, meanwhile, Protestants were dispatched to set up ‘colonies’ in what was a catholic country, particularly in the north of the island but not only. The process of ‘plantation’ as it became known, began with the king’s approval in 1608, saw the confiscation of the estates of Catholic landowners, and caused untold and lasting resentment between England and Ireland.

Parliament

James' reign in England was typified by a lack of formality in terms of court etiquette and protocol, something English nobles found odd. For example, any visitor could see the king at mealtimes, not a privilege ever given by his Tudor predecessors. The king’s Scottish speech often caused confusion, and he was also deemed a little uncouth, although his manners were likely not as bad as later writers have sometimes described them. The king has been described as having weak legs, an odd walk, and a tendency to slobber because of a large or loose tongue. All of these characteristics may point to a mild case of cerebral palsy.

Other habits which did not endear him to his English nobles were James’ love of spending and an undisguised pursuit of handsome young men who then gained undue power at court. The prime example of such a favourite is George Villiers, a very minor noble whom James made the Earl of Buckingham in 1617 (later upgraded to Marquis and then Duke) and who very often controlled who had access to the king in his final decade of rule.

Despite the culture shock, James’ reign was at least moderate in terms of dealing with the mixed religious factions in his kingdom of Protestants, Puritans, Catholics, and those who cared for none of these. The king’s real problem was politics. James was utterly convinced of his divine right to rule his kingdom with absolute authority, and this position brought him into frequent conflict with the English Parliament, even if he did in practice sometimes display a sense of compromise with his nobles. James’ Tudor predecessors had well understood the need to accommodate powerful nobles through Parliament, but James, used to a weaker commons institution in Scotland, did not perhaps grasp the differences in the two systems of government in Scotland and England. Matters of finance were a particular cause of trouble, with James dissolving a Parliament in 1611 and another in 1621. The Parliament of 1614 could not break an impasse over money and passed no legislation at all. In addition, the king’s attempt to politically unify Scotland and England was rejected by Parliament, although the Union Jack flag, which combined the flags of the two nations, was adopted by ships from 12 April 1606. There was, too, prolonged wrangling over the king’s need to raise funds for his lavish lifestyle as raising taxes was the domain of Parliament.

The Gunpowder Plot

Although Parliament and the king rarely saw eye-to-eye, there was one group of conspirators that did not like either. Early on in his reign, sometime in 1605, a group of Catholic rebels, angered by a new wave of laws in the Anglican Church against practising Catholics, decided to take drastic measures. The conspirators, led by Sir Robert Catesby, were certainly ambitious and they began tunnelling under Westminster Palace where Parliament met. This tunnel was abandoned when the conspirators realised it was easy enough to rent an empty chamber, actually a coal cellar, under that part of the building they required. In this chamber, they deposited a massive quantity of gunpowder with the express intention of blowing up the building when the king opened Parliament on 5 November. All the most powerful nobles would be present, and their deaths would have caused chaos in England, a situation pro-Catholic forces might then exploit to their advantage.

Fortunately, the plot was discovered before it was too late after one of the conspirators, one Francis Tresham, sent an anonymous letter to his brother-in-law, Lord Mounteagle, who would have been present on the fateful day and who was a noted Catholic peer; Mounteagle duly passed on news of the plot, and the king was eventually informed. When the chamber below the Palace was investigated at midnight on the 4th of November, a man was apprehended who had been guarding 35 barrels of gunpowder, one Guy Fawkes. Fawkes was a Catholic soldier of fortune and explosives expert who had recently come to England. Fawkes was taken to the Tower of London where, after a good deal of torture, he revealed the names of the conspirators who were ultimately hanged, drawn, and quartered, the terrible punishment reserved for traitors.

To celebrate the foiling of what became known as the Gunpowder Plot, the authorities encouraged commoners to light bonfires on the evening of the 5th of November, and this they did, starting a tradition which continues to this day.

The Bible, Americas, & Other Events

James’ eventful reign continued, and 1611 saw the publication of the first Authorised Version of the Bible, thereafter known as the King James Version or the Authorised Version because the king had permitted the massive undertaking. This version was a product of a conference involving Anglicans and Puritans at Hampton Court in 1605, held to decide on a definitive version of the sacred book. At that time, there were three major existing versions: the 1539 Great Bible of William Tyndale, the 1560 Geneva Bible, and the 1572 Bishop’s Bible. James’ version, compiled by a team of 47 scholars, translators, and bishops over seven years, proved to be an enduring one and became the standard interpretation for centuries thereafter in English-speaking countries.

In 1606, the king granted a royal charter to found colonies on the east coast of North America. In May 1607, Jamestown, named after the king, was founded in Virginia, and in 1616, Pocahontas (l. c. 1596-1617), famed daughter of Chief Powhatan (1547 - c. 1618) travelled to England and met James I at court. In 1620 the Mayflower sailed for North America with the pilgrim Puritan colonists who established the Plymouth Colony. Oddly, the Mayflower had received royal backing despite James’ stance against religious freedoms that caused the pilgrims to leave in the first place. The king had famously stated that his policy towards anyone not obeying standard church practices would be harsh: "I shall make them conform or I will harry them out of the land or else do worse" (Philips, 137). In 1624, Virginia became the King’s Royal Colony.

The flourishing of the arts continued as they had under Elizabeth I. James honoured William Shakespeare’s acting company by granting them the title of the ‘King’s Men’, and a significant number of the famous playwright’s works like King Lear, Macbeth, and The Tempest, were performed at the royal court. In another event with long-lasting repercussions, the game of golf was invented.

Death & Successor

James suffered various ailments in his later years, including arthritis, kidney problems, and gout. The king died, probably of a stroke, at the age of 58 on 27 March 1625 at Theobalds Park in Hertfordshire. The king was buried in Westminster Abbey alongside his Tudor predecessor Henry VII. James was succeeded by his surviving eldest son Charles who would reign until 1649. Unfortunately for everyone, including himself, Charles was even less accommodating to his nobles and political institutions than his father had been, and a crisis of the monarchy developed into a full-blown civil war. Charles was executed in 1649 and replaced by a republican system headed by Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658). The monarchy was eventually restored in 1660 when Charles’ son became Charles II of England (r. 1660–1685). The Stuarts would continue to rule until 1714.