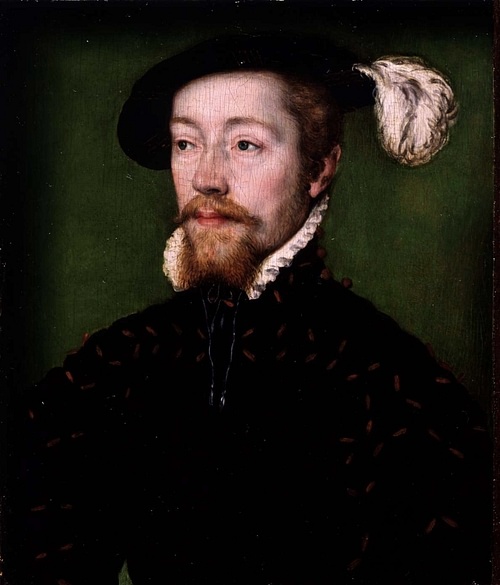

James V of Scotland ruled as king from 1513 to 1542. He succeeded his father James IV of Scotland (r. 1488-1513), one of the country's most popular Stuart kings, but as he was still a child, the early part of his reign was tempestuous with his mother and nobles battling for control of the regency. Ruling in his own right from 1528, the king's fiscal policies were unpopular, and his decision to forge closer ties with France through his marriages - first to the daughter of Francis I of France (r. 1515-1547) and then to Mary of Guise (1515-1560) - divided his kingdom. James died of illness within a month of a military defeat at the hands of an English army at Solway Moss in 1542; he was just 30 years of age. James V was succeeded by his infant daughter, Mary, Queen of Scots (r. 1542-1567).

Succession & Regency

James IV of Scotland had been one of the country's most popular kings, and certainly the most effective of the Stuart kings who had reigned since Robert II of Scotland (r. 1371-1390). In August 1503, James had married Margaret Tudor (1489-1541), daughter of Henry VII of England (r. 1485-1509), but relations between the two countries turned sour when war broke out between England and France during the reign of the next English king, Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547). France expected Scotland, its ally by treaty, to invade northern England, and this is what James IV did in 1513. The expedition was a disaster, and Scotland's army was crushed at Flodden Hill on 9 September. James IV, 9 earls, and 14 barons were all killed along with some 10,000 Scots.

James V was born on 10 April 1512 in Linlithgow Palace, none of his five siblings survived infancy. The new king was, then, merely 17 months old when his father died and so he needed a regent, even if he was crowned king on 21 September 1513 at Stirling Castle. The position as the king's guardian was fought over between his mother Queen Margaret, who remarried in 1514 to Archibald Douglas, 6th earl of Angus, and John Stewart (c. 1484-1536), the Duke of Albany and grandson of James II of Scotland (r. 1437-1460). With Margaret, sister of Henry VIII, involved in the regency, at least there was peace between England and Scotland, but when the Duke of Albany took over in July 1515, the government swung around to be pro-French again. When the duke sailed to France in 1524 to cement diplomatic relations, the queen seized the opportunity to retake the regency. The young James, meanwhile, blissfully pursued those pastimes expected to occupy a young noble: tennis, music, and jousting.

The shenanigans at court continued and eventually became more threatening for King James. From 1525 until 1528 the boy-king was kept a virtual prisoner by the Earl of Angus who had fallen out with Queen Margaret. The king was meant to be rotated every three months between different households to maintain some kind of balance in the fractious government, but the Earl of Angus refused to give him up. Finally escaping the clutches of his step-father in May 1528 and still only 16 years old, James took over the government in his own right the next month. The nobility swore allegiance to their king, and the Earl of Angus was obliged to seek safety in exile.

The French Alliance

Reaching maturity, James V married twice, both his queens being French. The first marriage was to Madeleine de Valois (1521-1537), daughter of Francis I of France. It was arranged far in advance by the Duke of Albany under the Treaty of Rouen of 1517. The actual marriage took place on 1 January 1537 in Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris, but, always having had frail health, Madeleine died of consumption six months later. On 12 June 1538 James married Mary of Guise, a member of a powerful and prominent Catholic family. The king was also known to have had many mistresses and fathered at least nine illegitimate children. With Mary of Guise James had one daughter, also called Mary, born on 8 December 1542.

Perhaps understandably, given his father's fate, James V pursued a foreign policy which was decidedly pro-French and anti-English. James visited France in 1536-7, and the king even failed to turn up to a proposed meeting with Henry VIII at York in September 1541 in order to discuss a peace deal. Meanwhile, at home, the queen influenced the king to take a stance against Lutheran Protestants, a decision which blackened his reputation when later Protestant writers drew up their histories of Scotland.

The king did his popularity no good whatsoever with his policies of high taxes, raising rents, confiscating estates, and general fleecing of the Church (much aided by appointing his many illegitimate children to key positions). This grasping approach was designed to fill the holes in the Crown's finances as James could only count on half the income his father had enjoyed. This was despite James receiving two generous dowries for his marriages but was a consequence of the nobles helping themselves to the country's wealth while he had been a child. Big-spending projects to renovate key palaces and castles were not helpful and necessitated more squeezing of the public purse.

The king's standing sunk even further with his attacks on those in the nobility who had plotted against him during his minority, most infamously Lady Glamis, the sister of the Earl of Angus, who was burnt at the stake in Edinburgh in 1537 on charges of treason. A suspicion of plots was perhaps understandable given the interminable manoeuvres of his regency years, and a legend grew that James stalked his realm in disguise, going by the name of 'the tenant of Ballangiech' to find out what nobles and commoners alike really thought of their king.

Despite the problems with the Douglases, it seems relations with the nobility were no better and no worse than in other periods. The king may not have entirely trusted his ordinary subjects as he spent a great deal of energy chasing after law-breakers across his realm, and the College of Justice was established in 1532. On the other hand, one could argue this was the duty of a good king to protect his law-abiding citizens.

James' deeds are difficult to determine objectively since so many contemporary sources are either from an English viewpoint or Protestant writers eager to denigrate his daughter Mary and her relations for her support of Catholicism. As the Oxford Kings & Queens of Britain notes, James V "has been called 'the most unpleasant of the Stewarts' - an unwelcome victory in a fiercely competitive field" (164). More recent work by 21st-century historians, however, is revising this wholly negative view of James' reign. Certainly, the king's trip to France in 1536 for seven months, when he left four nobles in charge of the kingdom, does suggest Scotland had finally achieved some political stability.

Death & Successor

Henry VIII eventually decided to take more direct action against his northern neighbour prior to his planned invasion of France. Henry sent the Duke of Norfolk to attack Scotland in force in 1542. Initially, the Scots held their own, and they were thus emboldened to launch a counterstrike at Solway Moss on the Scottish border on 24 November 1542. As it turned out, this became a bad loss for the Scots, not in terms of casualties but because over 1,000 Scotsmen were taken as prisoners. James V then died within a month of Solway, on 14 December at Falkland Palace. The cause of death was a lingering 'fever' (perhaps cholera or dysentery), which had prevented the king from being present at the decisive battle. The king was buried at Holyrood.

With no male heirs - two princes, James and Arthur, had both died in 1541 - James' daughter with Mary of Guise, Mary inherited the throne and became known to history as Mary, Queen of Scots. As she also became queen of France (r. 1559-1560) through marriage, the conflict with the Tudors in England rolled on. Mary was only one week old when she became queen, but when she reached maturity she schemed to take the English throne from Henry VIII's daughter Queen Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603). Mary was executed for her troubles, and her son became James VI of Scotland (r. 1567-1625). When Elizabeth died without an heir, James VI was invited to become the king of England as James I (r. 1603-1625) and so the Stuart line managed to unify the two crowns.