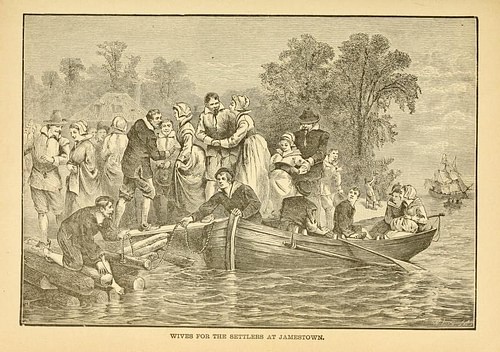

Jamestown brides (also known as tobacco brides) were young, single women transported from England to the Jamestown Colony of Virginia between 1620-1624 to be married to male colonists already established there. The women themselves had their own reasons for making the transatlantic crossing but were encouraged to do so by the Virginia Company of London.

These women were provided with dowries by the Virginia Company which had funded the expedition that established Jamestown in 1607. Many of the men who had traveled there afterwards had made whatever sum seemed sufficient to them and then returned to England to marry while others had died and still others had married Native American brides and gone to live with their tribes. One of the founders of the Virginia Company, Sir Edwin Sandys (pronounced Sands, l. 1561-1629) established the program of sending women-as-brides in 1619 in order to stop men from deserting the colony and provide stability, harmony, and a sense of community and so the Jamestown Brides program was initiated.

Young women would need to be recommended for the program, and these letters would accompany them on the voyage. Although it has often been claimed that the Virginia Company 'sold' women to the colonists, this claim has been repeatedly discredited. The argument is based on the charge that the Virginia Company charged the men of the company 120-150 pounds of tobacco for a bride (hence the epithet 'tobacco brides'), but this charge was to defray travel costs and dowries supplied by the company for the women. The tobacco was not a bride price, and men who wished to marry but could not afford the cost were asked to pay back what they could when they were able.

There were attempts by various parties to capitalize on the program and kidnap young women to be sent to Virginia against their will, and although this probably happened more often than reported, the official records state that these people were caught and prosecuted, usually executed, and the women freed. The program was still in effect in 1623 - though it is unclear how many women arrived that year - and was concluded when King James I of England (r. 1603-1625) revoked the Virginia Company’s charter and took direct control of the colony in 1624. The television series Jamestown (2017-2019), which received largely positive reviews for historical accuracy, is a modern-day drama of the Jamestown brides.

Jamestown’s Early Years

Jamestown was established as a commercial venture by the Virginia Company of London in 1607. The colony was far from an instant success because the roughly 100 men and boys who made up the expedition had little to no skill in agriculture and, further, the leaders had chosen to locate the settlement in a swamp. They only survived the first year through the generosity of Chief Powhatan (also known as Wahunsenacah, l. c. 1547-c. 1618). Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631) negotiated a peace with the Powhatan Confederacy which was strained by the colonists’ continual abuses of the natives through theft of food and land. The relationship was tried further by the arrival of more settlers in 1608, brought by one of the founders, Christopher Newport (l. 1561-1617) who had returned to England for supplies and brought back only more settlers who required food and shelter.

One of these new arrivals was Anne Burras, maid to Thomas and Mistress Forrest, who would become the first English woman to marry in the colony, wed to John Laydon, one of the colonists, in late fall 1608. Other women followed as Newport went back and forth across the Atlantic resupplying the colony with people but few supplies to keep them fed.

Captain John Smith was injured in a gunpowder accident in October of 1609 and returned to England for treatment, but even before he left, relations with the Powhatan tribes had soured owing to the continual neediness of the colonists and their repeated theft of food and land. Their behavior finally resulted in limits being placed by Chief Powhatan on interaction with the colonists and, finally, his order of 1609 that colonists should remain inside the fortifications of Jamestown; those found on Powhatan land would be killed.

Powhatan’s order contributed to what is known as the Starving Time in Jamestown during the winter of 1609-1610 during which people ate dogs, horses, vermin, corpses, and in one case a woman. An unnamed colonist, according to John Smith:

Did kill his wife, powdered her, and had eaten part of her before it was known; for which he was executed, as he well deserved; now, whether she was better roasted, boiled, or carbonado’d, I know not, but of such a dish as powdered wife I never heard of. (411)

In May 1610, the new governor, Sir Thomas Gates (l. c. 1585-1622) arrived and, finding only 60 colonists left alive and Jamestown in near ruins, ordered it abandoned. He had loaded the survivors on board and was making his way downriver when he was met by another ship carrying the aristocrat Thomas West, Lord De La Warr (l. 1577-1618), who ordered him about, and Jamestown reestablished. West instituted new, harsh, policies concerning the Native Americans and set off the First Powhatan War (1610-1614), which killed over 400 colonists. The war did not stop the arrival of more settlers from England, however, and many of them women. Cecily Jordan Farrar, who would become the matriarch of the well-known Farrar family, arrived in 1610 as a ten-year-old girl whose name appears on a passenger list with 20 women.

Even so, the ratio of male-to-female in the colony remained approximately 7-1. Men were leaving the colony to marry Native American brides or were returning to England to marry and many more, of course, were dying in the war, from malnutrition, or from disease. In 1611, Sir Thomas Dale arrived and instituted his famously strict laws which prohibited marriage to natives, but this does not seem to have stopped the constant turnover of the male population.

The Jamestown Brides

John Rolfe (l. 1585-1622), who had arrived with Gates, planted a successful tobacco crop which saved the colony by 1614 and this sudden economic boom attracted more colonists but still not enough women. The First Powhatan War ended with the marriage of John Rolfe to Pocahontas (l. c. 1596-1617), daughter of Chief Powhatan, in 1614, establishing a time of calm and prosperity known as the Peace of Pocahontas (1614-1622). During this period, colonists and natives traded with each other and interacted with few conflicts, encouraging greater stability. Jamestown still had more of the flavor of a military outpost than a commercial enterprise or colonial settlement, however. The Virginia Company recognized that it needed a stabilizing force, and their answer to the problem was the Jamestown Brides program.

Sir Edwin Sandys, who was then treasurer of the Virginia Company, also understood that the colony needed direct, hands-on, representational government which could address problems quickly instead of sending word back to England all the time. In 1619, he ordered the establishment of the House of Burgesses and that same year initiated the bride program. The company had done themselves no favors thus far as they had previously tried to stabilize Jamestown first by sending homeless children, “12 years old and upward” who would serve as indentured servants until the age of 21 (Neill, 161) and then proposed to solve the problem of the overcrowding of England’s prisons and their own need for more colonists by shipping convicts to Virginia; neither of these programs added anything to the colony’s stability.

Sandys had leaflets posted across England and printed in papers advertising the new program. The advertisements emphasized the good life awaiting women in Virginia and the guarantee of marriage to a man of means. The Records of the Virginia Company make clear that women were free to choose their own mates and would not be compelled to marry anyone they found disagreeable. In a letter to the colonial government, they say:

We have used extraordinary care and diligence in the choice of them and have received none of whom we have not had good testimony of their honest life and carriage, which together with their names, we send there enclosed for the satisfaction of such as shall marry them…this and their own good desserts, together with your favor and care, will, we hope, marry them all unto honest and sufficient men, whose means will reach to present re-payment; but if any of them unwarily or fondly bestow herself (for the liberty of marriage we dare not infringe) upon such as shall not be able to give present satisfaction, we desire that at least as soon as ability shall be, they be compelled to pay the true quantity of tobacco proposed and that this debt may have precedence of all others to be recovered. (Neill, 246-247)

Tobacco served the same purpose as legal tender at this time. The price for repayment of passage, food, and modest dowries for the women was 120 pounds of tobacco in 1620 and 150 pounds by 1622 (approximately $5,000.00 in today’s currency). The high price of repayment for sending a man a bride of good family and character was thought to dissuade those of little means from attempting to court any of the women, thereby assuring the brides of a comfortable and stable future.

The Women

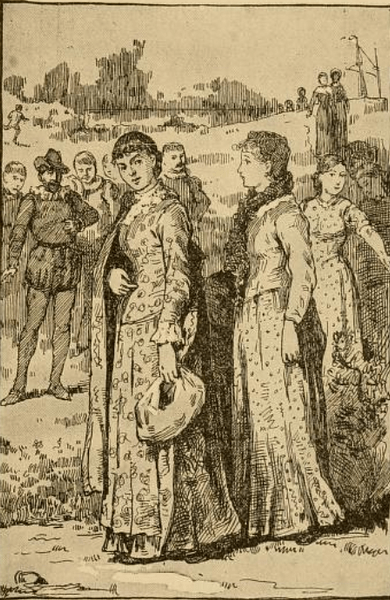

Those who chose to participate in the program saw it as a chance at a new life unhindered by the rigid social hierarchy of England. Girls from poor families had slim hopes of acquiring a dowry that would enable them to marry well, but through the program, a modest dowry was provided as well as the promise of a man of means as a husband. Young girls and women who worked all day as domestics in the homes of the wealthy saw in the program a real hope that one day they might own their own home and perhaps order about their own servants. 90-100 women arrived in 1620, a ship – the Marmaduke – carrying 13 women and possibly another with more in 1621, and another of equal or greater number in 1622. Scholar Misha Ewen comments:

The women who arrived in this period had personal motivations for voyaging to Virginia. They relied on their own faculties to seek out opportunities in Virginia, including Abigail Downing, a widow who voyaged to the colony in 1623. She paid the cost of her passage so that she would be "free to dispose of herself when she commeth to Virginia" with the intention of marrying an "honest man." Neither was she misled about conditions in Jamestown, promising to "take pains and do all service that is fit" in order to "earn her diet." In England, opportunities to marry and start families in independent households were hindered by the economic and social climate. Population growth accelerated in the late sixteenth and seventeenth century at the same time that real wages fell, leaving many underemployed and impoverished. Without decent earnings, couples could not afford to settle down. The thirteen women aged between sixteen and twenty-eight, who departed for Virginia aboard the Marmaduke in 1621, would have been acutely aware of this reality. (Musselwhite, et. al., 138)

After 1622, upon arriving in Jamestown, the women were housed in their own small village known as Maid’s Town; prior to 1622, they were presumably taken in by members of the company or were designated housing in town. The official records of the program emphasize the good fortune of the participants and their bright future but, as scholar Jennifer Potter notes:

While account books and ledgers can tell you the names of the passengers taken on board, they cannot tell you what those passengers were thinking, or how the women viewed their prospects as they waited [for transport to the New World]. (17)

The women’s skills, backgrounds, family connections, and class were all part of the packet of papers delivered by the Virginia Company to the colonial government, and it is probable that many of the women would have felt very much like horses, cattle, or hunting dogs whose pedigree would be inspected before they were approved of and taken in. Potter comments:

In putting together its prospectus for potential husbands, the Virginia Company took pains to enumerate the women’s accomplishments. Provenance alone was sufficient guarantee of worth for most of the gentry daughters among them while skills listed for the lower-status women were generally of two sorts: robust, practical skills in housewifery on the one hand, and more refined needlework or knitting skills on the other. (20)

Women were introduced to prospective husbands at gatherings sponsored by the company’s men and courtship overseen publicly by the ladies of the community. Although the official records claim they had never been misled regarding life in Jamestown, reports by men who left the colony make clear how the Virginia Colony presented a much brighter picture of life in the New World than they found in reality. The Peace of Pocahontas provided Jamestown and its satellite settlements a degree of calm and prosperity and, certainly, the profitable tobacco cash crop made many planters wealthy, but life in Jamestown overall was still difficult, and the peace did not last.

Conclusion

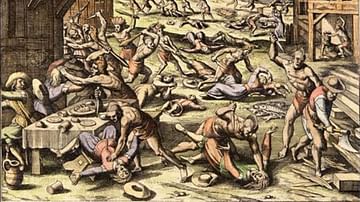

Pocahontas died in 1617 on her return trip from a promotional tour of England, but Wahunsenacah maintained the peace until his death c. 1618. Since 1610, the colonists had continued to encroach on Native American land, desecrate sacred sites, steal native corn and other foodstuffs, and generally abuse the indigenous tribes of the region. On 22 March 1622, the new Chief Powhatan, Opchanacanough (l. 1554-1646) launched a one-day offensive known as the Indian Massacre of 1622, killing over 300 colonists and starting the Second Powhatan War (1622-1626). This war would cost even more lives and, even after it was officially ended, hostilities continued.

The war did nothing to dissuade women from participating in the program, however, and more arrived in 1623 and early 1624. Disease and death in childbirth took a number of women not killed in native attacks, while malnutrition, domestic abuse, and accidents took more. Of the more than 150 women who participated in the Jamestown Brides program only a little more than 30 lived to see their sixth year in the colony. King James I responded to the Indian Massacre of 1622 by dissolving the Virginia Company in 1624 and issuing a royal charter for the colony, taking direct control himself.

James I ended the bride program, but by this time, Sandys' vision of a stable colony of families had been realized. Jamestown and the other settlements of the Virginia Colony still faced a number of significant challenges, but they were now peopled with families instead of single men. Other women, with and without husbands, arrived later, encouraged by the fact that Virginian law was far less strict than that of England, allowing women greater personal rights.

Records of the time show that women could refuse to recite the standard vows of marriage, could make and break business contracts and marriage arrangements, and widows could own and manage their husband’s estates. The Jamestown brides who survived their early years in the colony became the respectable women of the Virginia Colony and, in a number of cases, were able to realize the dream of owning their own home and directing their own lives.