The Jamestown Colony in Virginia was the first permanent English settlement in North America founded in 1607. It was the third attempt of the Virginia Company of London to establish a permanent trade center in the Americas following the failures of the Roanoke Colony (1587-1590) and the Popham Colony of 1607-1608.

The primary objective of the Jamestown Colony was profit for the shareholders who financed the expedition, and at first, it seemed a failure. Those who had been selected to establish it turned out to be unfit for the task except for Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631) who was able to negotiate with the native Powhatan tribe and assume leadership of the colonists.

After Smith left the settlement for England in 1609, however, the colony seemed doomed, enduring the harrowing winter of 1609-1610 which killed off most of the colonists. A supply ship in May 1610 brought two of the men who would reverse their fortunes: John Rolfe (l. 1585-1622) and Sir Thomas Gates (l. c. 1585-1622) and another, in June 1610 CE would bring the third, Thomas West, Lord De La Warr (l. 1577-1618).

Rolfe had a novel idea for a new blend of tobacco which became the colony's cash crop, Gates organized the colony as governor, and De La Warr prevented its desertion and directed Gates. In 1611, Sir Thomas Dale (l. c. 1560-1619) arrived who would initiate the founding of the Henricus Colony of Virginia and begin the removal of the indigenous Powhatan tribes from the surrounding lands.

Tobacco was a labor-intensive crop, which led to the policy of indentured servitude and, eventually, slavery. In 1619, the first Africans arrived in Jamestown and, at first, seem to have worked in the same capacity and under the same policies as indentured servants.

That same year, the assembly of the House of Burgesses was convened, the first English representational governing body in the Americas and, also, the Jamestown Brides program was launched. In 1622, the Powhatan Confederacy launched a united attack to drive the settlers out and, in 1624, King James I of England (r. 1603-1625) took direct control of Jamestown through a royal charter.

The settlement continued to thrive until 1699 when it was abandoned in favor of Williamsburg as the colonial capital. The site was purchased by a couple, Mr. and Mrs. Edward Barney, in 1892 to prevent development, and preservation efforts began in 1900 with archaeological efforts continuing to the present day in the area, now a national park.

Early Colonization Efforts

European colonization of the Americas began with Christopher Columbus (l. 1451-1506) who colonized the islands of the Caribbean for Spain between 1492-1504. The success of these early colonies and the wealth they generated inspired Spain to send others to search for gold and expand its colonial presence until, by the end of the 16th century, Spain held lands ranging from the Caribbean through South, Central, and southwestern North Americas. France and the Netherlands had also claimed lands in the region during this same time. England, therefore, was a latecomer.

Initially, England contented itself with funding privateers like Sir Francis Drake (l. c. 1540-1596) and Sir Martin Frobisher (l. c. 1535-1594) to seize the cargo of Spanish ships returning from their colonies or raid Spanish port cities, but eventually, Queen Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603) understood it would be more efficient to establish their own bases in the Americas where ships could be built and launched against the Spanish. She gave the job of organizing a concerted effort to Sir Walter Raleigh (l. c. 1552-1618) who sent the Amadas-Barlowe Expedition to claim suitable land, not already claimed by a European nation, in 1584.

Receiving a good report from his captains upon their return, Raleigh named the region they had mapped Virginia after Elizabeth, the virgin queen, and sent another expedition, under Ralph Lane (d. 1603) who established a short-lived colony at Roanoke (in modern-day North Carolina). Lane's colony would not survive, mainly owing to Lane's mistreatment of the natives and betrayal of their initial hospitality, and neither would a second one established by John White in 1587, the so-called “lost colony”.

Establishment of Jamestown

Queen Elizabeth I died in 1603 and was succeeded by James I who reignited colonization efforts. Unlike Elizabeth I, James I had no need to fear intervention from Spain as the Spanish Armada had been crippled and largely destroyed in 1588 through the efforts of Drake, Frobisher, and a sudden storm. James I granted charters to two joint-stock companies (business ventures in which investors buy shares expecting a return), the Virginia Company of London and the Virginia Company of Plymouth.

Both charters allowed them to establish settlements in North America as long as they did not infringe on the other's territories. The Virginia Company of London sent the expedition which would found Jamestown in Virginia; the Plymouth company's expedition founded the Popham Colony in present-day Maine. The Popham Colony would only last 14 months before it was abandoned.

The site of the Jamestown colony was selected based on the Amadas-Barlowe Expedition charts of 1584, but in order to protect it from passing Spanish ships, the captains navigated up an inlet which they named the James River and claimed a peninsula in a swampy region as their site. The success of the Spanish had led the English to believe that the Americas were a land of plenty, teeming with gold, silver, and precious gems just waiting to be found, and a large percentage of the colonists were upper-class noblemen who signed on believing they would just pocket whatever gold was found lying about and return home.

The reality of the situation was that there was no ready-at-hand gold to be found, the colonists had arrived too late to plant crops, and many did not even know how to do so, and the marshlands – which the indigenous people avoided – was a breeding ground for mosquitoes; most of the colonists were dead within a few months of their arrival.

John Smith & Pocahontas

Captain John Smith came from a working-class, agricultural background, and he relates in his journals and other works how completely useless the upper-class colonists were in sustaining themselves and had to force them to build a stockade for protection (later known as Fort James). Newport explored up and down the James River in one of the smaller ships to find a site more conducive to agriculture while Smith initiated friendly relations with the Powhatan tribe's leader Chief Powhatan (also known as Wahunsenacah, l. c. 1547 - c. 1618).

The initial friendly relationship with the local natives would deteriorate due to abuses by the colonists. Newport left for England to bring back more supplies and, as food grew scarce and the colonists could not – or would not – produce their own, they took to stealing from the Powhatans. The situation grew worse when Newport returned with the supplies and 100 new colonists who found no housing, food, nor anything approaching what they had been promised back in England. Newport left on another supply run, and Smith instituted his policy of “those that will not work, will not eat”, forbade stealing from the Powhatans, and set chores for the settlers.

According to an early version of his account of relations with the Powhatans, he first met Pocahontas (l. c. 1596-1617) when she was ten years old and was sent by her father to Fort James to negotiate the release of some Powhatan warriors who had been captured after an altercation. Neither party spoke the other's language, but the Powhatans were released with gifts for the chief, and Smith presented Pocahontas with “such trifles as contented her” (Smith, 35).

In a later account, he relates how, while on a scouting mission of the wider area, he was captured by the half-brother of Wahunsenacah, Opchanacanough (l. 1554-1646), who treated him like an honored guest and brought him to the chief. Wahunsenacah ordered him thrown to the ground to be executed, but Pocahontas intervened, saving his life.

Modern-day scholars usually dismiss this story as a later fabrication or as Smith misunderstanding a ritual in which he would be “killed” and reborn as a member of the Powhatan tribe. The debate on the meaning and accuracy of this account continues, but it is clear that Pocahontas was at least 16 years younger than Smith, and nowhere in any of Smith's accounts is there any evidence of the romantic relationship between the two, which has become so much a part of the Jamestown mythology.

The Starving Time & Prosperity

Smith's discipline and organization of the colony enabled the settlement to survive but he was frustrated at the influx of even more people on Newport's return with a second supply ship. By August of 1609, there were over 500 settlers at Jamestown who required food, clothing, and shelter all of which were in short supply. Smith was injured by a gunpowder explosion and left the colony to return to England in October of 1609, and the settlers were left to fend for themselves. At the same time, Chief Powhatan refused to allow the colonists to drain anymore of his people's supplies.

This did not go well as the colonists, which by now included women and families, could not make a living from the land and were vulnerable to the diseases encouraged by the damp marshy locale and crimes perpetrated against each other. The winter of 1609-1610 is known as the Starving Time because, as supplies ran out, people ate rats and other vermin, then dogs, then horses, and finally the corpses of the dead. One colonist - who was later executed - even killed and ate his wife.

A third supply ship, commanded by Sir George Somers (l. c. 1554-1610) was supposed to have reached them before they ran into any trouble but his ship, the Sea Venture, was wrecked in a hurricane off the coast of Bermuda. Somers and his crew - which included Newport, John Rolfe, Sir Thomas Gates, and Stephen Hopkins (l. 1581-1644, later of the Mayflower expedition) - built two new ships on Bermuda and arrived in Jamestown in May of 1610.

Gates assumed control of the settlement – whose population had fallen from around 500 to less than 150 – but felt the colony was simply unsustainable. He ordered the people to board the ships and abandon Jamestown and they were navigating their way up the James River when another ship, carrying Lord De La Warr, arrived and countermanded the order; all ships would return to the colony and the passengers disembark.

De La Warr, Rolfe, & Dale

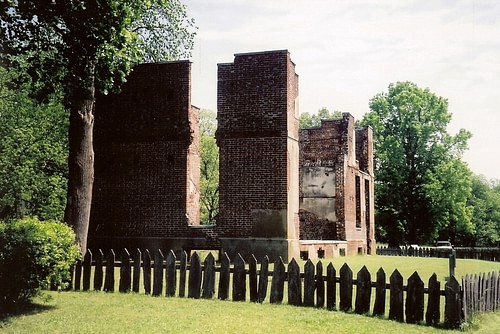

In a letter to the Virginia Company composed shortly after his arrival, De La Warr writes that they found the colony in a sorry state, appearing “rather as the ruins of some ancient fortification than that any people living might now inhabit it” (Neill, 39). De La Warr ordered Somers to return to Bermuda for fresh supplies and then reorganized the colony and turned the administration of its operation over to Gates. Lands were surveyed and parceled out for cultivation and John Smith's policy regarding working for one's food was maintained. De La Warr departed from Smith's policy regarding the natives, however, and instituted harsher measures, igniting the First Powhatan War (1610-1614) which would kill over 400 colonists.

Rolfe had brought with him a hybrid seed blend he had cultivated from Spanish tobacco which he felt would do well in Virginia soil. By 1611, Rolfe successfully harvested his first crop which would become a commercial success in Europe. Jamestown was not only saved by the tobacco crop but flourished. That same year, Sir Thomas Dale arrived with more supplies, colonists, and cattle and instituted further laws. De La Warr fell ill in 1613 and turned over his authority to Sir Samuel Argall (l. c. 1580-1626), afterwards leaving for England.

Dale was tasked by the Virginia Company with establishing a colony to defend against the Spanish and understood that more, and better, land was required for the tobacco crop. He established a new colony, Henricus (named after his benefactor, Henry, son of James I), upriver from the old colony. Concurrently, evangelical efforts were underway to convert members of the Powhatan Confederacy to Christianity, and Dale established a college outside of Henricus to further their education as well as a hospital - the first English school and medical institution in North America.

By 1614, John Rolfe was a wealthy man with a large plantation and married the newly converted Pocahontas (who took the Christian name Rebecca) which ended the First Powhatan War. As more land was cleared for tobacco, cattle, and settlement, the Powhatans were pushed further and further inland from the waterways which had always been their traditional means of livelihood and of travel, but the marriage of the wealthy Rolfe to the noble Pocahontas maintained good relations between the indigenous tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy and the immigrants.

In 1616, Rolfe took Pocahontas and their young son, Thomas Rolfe (l. 1615- c. 1680), to England on what amounted to a public relations tour for the Virginia Company to encourage further investment in the colony. Pocahontas was well received and became a national celebrity but died in 1617 just prior to their return. Chief Wahunsenacah died shortly afterwards, and Opchanacanough assumed leadership of the Powhatan Confederacy at about the same time the House of Burgesses was convened to pass laws regarding the colonizers of the former Powhatan lands.

Powhattan Wars, Servitude, & Rebellion

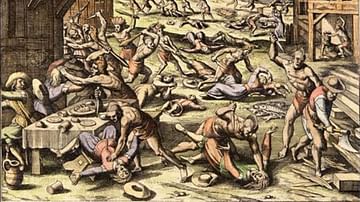

The Powhatan Wars can be understood as periodic engagements beginning in 1610, when Jamestown began to expand, and concluding in 1646, when Opchanacanough was shot in the back, while a prisoner, and killed. The most significant encounter is the so-called Indian Massacre of 1622 when Opchanacanough organized the confederacy in a coordinated attack that killed over 300 settlers and destroyed the colony of Henricus. James I rescinded the Virginia Company's charter afterwards in 1624 and took direct control through a royal charter. A long palisade was constructed by the settlers marking a boundary between their lands and those of the Powhatans and a truce was called in 1626, establishing an uneasy peace.

Shortly after Rolfe's first tobacco crop proved successful, indentured servants began arriving in Jamestown. These were people who could not afford to book passage to the New World and so signed a contract known as an indenture; so called because it was torn or cut with “teeth” indentations across the center and each party kept one half; the two could be put together later to prove authenticity. Indentured servants agreed to work for a period of time (usually seven years but sometimes four) and would then receive a tract of land. The first Africans arrived in the colony in 1619 but, as slavery was not institutionalized in North America at this time, they seem to have been treated the same as indentured servants. Scholar David A. Price clarifies:

Although it is tempting to assume that these first recorded Africans in English America were also the first slaves, there is evidence to suggest they were not. They may instead have had the legal position of indentured servants, like many of the white newcomers, eligible for freedom after completing a period of service. (197)

This dynamic changed in 1640 when a black indentured servant named John Punch refused to fulfill his contract and left his master's service along with two white servants. The three were caught and returned and, while the two white servants only had their terms of servitude extended by four years, Punch was condemned to continue as a slave for life. By 1661, slavery would be institutionalized in Virginia and black settlers no longer seen as the equals of whites.

Conclusion

As per the terms of indentured servitude, more and more former laborers had become landowners themselves. The lands of these later owners were further inland and considered of less worth than those on the coast, however, and more vulnerable to attacks by natives whose traditional homes were being overrun by more and more settlers. One of these later landowners, Nathaniel Bacon (l. 1647-1676), raised a revolt (Bacon's Rebellion) in 1676, demanding the slaughter or relocation of Native Americans in the region and the overthrow of Governor William Berkeley (l. 1605-1677) whose administration he claimed was corrupt in favor of the older, coastal landowners and the natives.

Bacon and his followers burned Jamestown, forcing Berkeley and his supporters to flee the town, but before he could do more, he died of dysentery and the rebellion failed. The revolt ended indentured servitude, the increased need for laborers encouraged the slave trade, and Native Americans were further denied land and civil rights. Jamestown was rebuilt but, when the statehouse accidentally caught fire again in 1698, the colonial capital was moved to the area known as the Middle Plantation, later Williamsburg, and Jamestown was eventually abandoned. Its legacy continued, however, as more slaves were brought from West Africa and more of the Native Americans were forced from their land into reservations to make room for more colonists pursuing the same American dream that had drawn the first to the land of plenty.