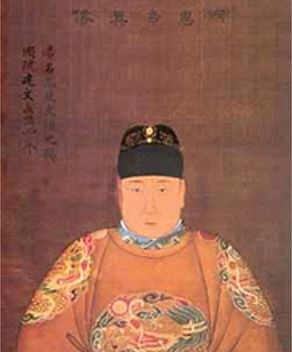

The Jianwen Emperor (r. 1398-1402 CE) was the second ruler of the Chinese Ming dynasty (1368-1644 CE). Following a civil war and Jianwen's mysterious disappearance, his uncle took over the throne and ruled as the Yongle Emperor (r. 1403-1424 CE). A victim of his successor's prejudiced rewriting of official court records, Jianwen may have been a reasonable ruler who sought to reverse the harsh laws and treatment of officials that had typified his grandfather's reign, the Hongwu Emperor (r. 1368-1398 CE).

Zhu Yunwen's Succession

The Ming dynasty was founded by the Hongwu Emperor in 1368 CE, and it was he who sparked off a rumpus at the imperial court over who should be his successor. The problem was that although Hongwu had 26 sons, the carefully groomed heir, his first son Zhu Biao, had died prematurely in 1392 CE. Instead of choosing his own second eldest son, Hongwu decided on the eldest son of Zhu Biao. This policy became the convention throughout the Ming dynasty - the eldest son of the Empress would inherit the throne, and if he died before this was possible, the right went to his eldest son. Consequently, when Hongwu died in 1398 CE, he was succeeded by his grandson Zhu Yunwen (aka Huidi, b. 1377 CE). Aged just 21, the new ruler of China took the reign name of the Jianwen Emperor, meaning 'Civility'.

Civil War with the Prince of Yan

Unfortunately for the new emperor, his grandfather's policy of jumping a generation was not welcomed by all, especially not Hongwu's second son, known as the Prince of Yan (and as Zhu Di, b. 1360 CE). The prince was ambitious, he had already shown himself an able military commander in campaigns against the Mongols, and he wanted the throne for himself. Significantly, the prince's claim was backed by his large army stationed in the north-east provinces of China and meant to protect the area around Beijing. The final straw was Jianwen's decision to remove the title of prince from the first and other sons of an emperor, the Prince of Yan included. The ex-prince began to incite rebellion, questioning Jianwen's legitimacy to rule and spreading rumours that the young emperor was unduly influenced by corrupt and self-serving officials.

A bitter civil war followed, and it would last, on and off, for three years. The Prince of Yan, with a better-organised army and more able commanders at his disposal, was the final victor, and he became emperor Chengzu, taking the reign name Yongle Emperor, meaning 'Eternal Contentment' or 'Eternal Joy'. The Jianwen Emperor simply disappeared. There were some accounts that he had been killed during the civil war when a fire broke out in the imperial palace at the Ming capital Nanjing. Another, more intriguing rumour spread that the former emperor had managed to escape the city disguised as a monk. Whatever his fate, nothing more was ever heard of the Ming Dynasty's second emperor.

The Yongle Emperor's Revisionism

Having taken the throne by force, and given the importance in Chinese culture that the emperor was supposed to be the Son of Heaven and specially chosen by God to rule, the Yongle Emperor spent much of his long reign trying to legitimise his position. A purge was carried out in the civil service, sparked off by the refusal of the noted Confucian scholar-official Fang Xiarou to draft the proclamation of Yongle's enthronement. Xiarou was executed by dismemberment, any of his known associates in the government were executed and so, too, were all his relatives to the tenth degree. Yongle's move of the capital from Nanjing to Beijing in 1421 CE, besides having strategic advantages to defend China's northern borders which were continuously threatened by the Mongols, also allowed the emperor to start afresh and leave behind any officials and bureaucrats still loyal to his missing predecessor. Yongle made another policy decision with lasting consequences when he greatly favoured eunuch officials, again a move that perhaps signified his lack of trust in the established state apparatus. This preoccupation with loyalty would manifest itself in other ways, too. In 1420 CE, the emperor established a sort of secret service, the Eastern Depot, headed by his chief eunuch and given the task of hunting down any suspect officials.

Yongle was not only concerned with the future but also the past. The emperor ordered the scholar-officials at the state archives to destroy documents and falsify the historical records so that Jianwen was 'airbrushed' out of Chinese imperial history. The whole civil war was noted as a mere 'Quelling of Disturbances' in the official records. Discussion of the discredited Jianwen officials was taboo and possessing any of their writings was forbidden; anyone caught doing so received the death penalty. Nevertheless, some historical records remain from Jianwen's reign and they indicate the young emperor had reversed some of the policies of his grandfather. Hongwu had centralised the government and removed many of the political limits on the emperor's power. For example, he eliminated the Secretariat of ministers which had advised emperors. Jianwen restored some of the powers back to the most senior ministers in his government and he also revised a number of the harsher laws in his grandfather's law code, the Da Ming lü. We know that Hongwu had favoured the Buddhist and Taoist monasteries but Jianwen removed some of these privileges.

Jianwen's Shadow

Finally, some scholars have suggested that one of the reasons the Yongle Emperor sponsored the famous seven voyages of the explorer Zheng He (starting from 1403 CE), was to find out if the Jianwen Emperor really had escaped alive and was in hiding somewhere in Southeast Asia plotting a comeback. The main reasons for the expeditions - which went from Southeast Asia to India and then the Persian Gulf and east coast of Africa - was to revive and extend the traditional Chinese tribute system but, even here, the missing Jianwen may have had some influence. The Yongle Emperor knew that he needed legitimacy for his violent takeover and one of the most enduring methods to display to the people that the man on the imperial throne was truly the Son of Heaven was to have foreign states send tribute. When ambassadors came to the Chinese capital offering up luxury goods, fellow rulers were acknowledging that China was the 'Middle Kingdom' and its emperor the most powerful ruler in the region. Jianwen's reign, then, may have been short but he had cast a long shadow over his successor's two decades in power.