Karma is a Sanskrit word that primarily means 'action' but for South Asian Religions (and Philosophy) it is not limited to that as the term has gained various meanings and connotations over time. The term karma connects actions and results. Good and bad happenings experienced in this life are aggregate results of deeds in this and previous lives. This is known as the Law of Karma and it is regarded as a natural and universal law. Karma not only justifies the present situation of an individual but also rationalizes the cycle of birth and death (or saṃsāra) which is common in South Asian Philosophy.

Early Sources

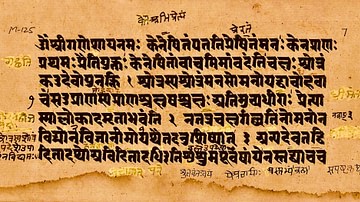

The idea of Karma first appears in the oldest Hindu text the Rigveda (before c. 1500 BCE) with a limited meaning of ritual action which it continues to hold in the early ritual dominant scriptures until its philosophical scope is extended in the later Upanishads (c. 800-300 BCE). The term gains a more philosophical weight when the consequences of actions are attached to it. Thus karma gains a moral or ethical dimension.

The autonomous causal function associated with karma in South Asian traditions largely differs from the perspective of Abrahamic Religions where God (divine agency) rewards or punishes all human actions. Thus, the Law of Karma vindicates God from the existence of evil. The actual functioning of karma, the intervention of the Almighty in overturning it, the ending of karma, etc. are intricate details which vary from tradition to tradition.

Karma in Practice

Karma as a reciprocal concept includes both action and intent. All good actions like charity to the needy, service to elders, help to kin, etc. and all good intentions or well-wishes for others are rewarded and vice-versa. This Law of Karma inspires an individual to follow two things (a) good deeds to avoid bad reciprocal results (b) adhere to some spiritual action to neutralize the effects of karma. The second point may not be common to all traditions. The ending of karma and karmic consequences releases one from the cycle of birth and death commonly known as mokṣa or nirvāṇa.

From a philosophical perspective, there is a lengthy debate between free-will and karma. If one is acting inappropriately now, one can justify this as a consequence of one's past only if karma exists. However, along with the theory of karma, one is bestowed with volition and one can act according to one's conscience. So while reaping the fruits of one's past karma, good or bad, one is accumulating new karma as well as acting on one's free-will. This also gives one an opportunity to act in such a way that one may liberate oneself.

Karma in Different Traditions

In Hinduism, the theory of karma is more dominant in the Vedānta School. For some schools like Mīmāṃsā, the role of karma is almost negligible. Most traditions agree on three types of karma: prārabdha, saṃcita, and kriyamāṇa which mean karma to be experienced in this lifetime, latent karma which we have not yet reaped, and karma that will result in our future lives, respectively. There is also a concept of jīvanmukta or a living individual who is actually liberated and thus does not accumulate karma any more. In later Hindu traditions which are primarily theistic, the grace of God plays an important role in overriding the karmic implications or completely relieving one and thus leading to mokṣa.

In Buddhism, essentially there is no soul. The unresolved karmas manifest into a new form composed of five skandhas (constituent elements of a being) in one of the six realms of saṃsāra. The eventual nirvāṇa (salvation) comes through the annihilation of residual karma which means the ceasing of the alleged existence of being. The actions with intention (cetanā) carried out by the mind, body and speech and which are driven by ignorance, desire and hatred lead to implications that tie one down in saṃsāra. Following the Eightfold Path - the set of eight righteous ways of thinking and acting suggested by Buddha - one can attain nirvāṇa.

In Jainism, karma is conceived as a subtle matter pervading the entire Universe in form of particles. These extremely subtle particles cling to the soul obscuring its intrinsic pristine form. It is sometimes described as the contamination that infiltrates the soul and taints it with various colours. Liberation is achieved through following a stringent path of purification. For Jainism, given the absence of an external divine agency, the Law of Karma becomes predominant as a governing law and a self-sustaining mechanism that governs the Universe.