Katharina Zell (also known as Katharina Schütz, Katharina Schütz-Zell, l. 1497-1562) was a reformer, theologian, and prolific writer in Strasbourg who helped establish the basic tenets of the Protestant Reformation without advancing sectarian interpretations. She is regarded as the first ecumenical reformer as she accepted and ministered to people of different sects without judgment.

She claimed to have been called by God to be a 'Church Mother' at the age of ten, meaning one who cared for all members of the Church without regard to differences in belief. In 1523, she married the pastor Matthew Zell (l. 1477-1548) at a time when clerical marriages were highly controversial and associated with the works of Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546), regarded as a heretic by those who rejected his views. Zell and her husband were attacked for their marriage, inspiring her best-known work, written in response, Katharina Zell's Defending Clerical Marriage (1524), an open letter that became a bestselling pamphlet.

She continued to write for the rest of her life, corresponding with many reformers of different sects and meeting Luther and Philip Melanchthon (l. 1497-1560), Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531), John Calvin (l. 1509-1564), and she was friends with Martin Bucer (l. 1491-1551) and Wolfgang Capito (l. c. 1478-1541). She and her husband opened their home to anyone in need, regardless of their beliefs, and provided a safe haven for refugees as well as a center for intellectual and spiritual development.

After her husband's death in 1548, he was succeeded as pastor by Ludwig Rabus (l. c. 1524-1592), who had lived with the Zells and served as Matthew Zell's intern. Rabus denounced the famous tolerance of the Zell household and Katharina's writings, and she responded with A Letter to the Whole Citizenship of the City of Strasbourg from Katharina Zell (1558) defending herself, religious tolerance, the rights of women to minister to others, and answering each of RabusI charges eloquently. This work, like her others, was a bestseller and among her last before she died of natural causes in 1562. She is recognized today as among the most significant early reformers.

Early Life & Conversion

Katharina Schütz was born on 15 July 1497 (though some sources suggest 1498) in Strasbourg and was named after the Italian mystic and author Catherine of Siena (l. 1347-1380). Her mother, Elizabeth Gester (d. 1525), and father, Jacob Schütz, were of the artisan-merchant class, and she had nine siblings (four older and five younger), all of whom were educated. The family was well-off and devoutly Catholic, and since the Church discouraged the practice of educating girls, Katharina was home-schooled until she was old enough to attend the girls' school, open to those of the upper-class as a kind of 'finishing school' to prepare girls for marriage, where she seems to have learned some rudimentary Latin. She was never fluent in Latin and knew no Greek but read widely in her native German and was especially interested in church history.

She later claimed to have had no interest in marriage or taking the vows of a religious order but dedicated herself to the service of God at age ten, planning on supporting herself as a weaver of tapestries. She attended worship services at Saint Lawrence Cathedral in Strasbourg which, like all houses of Christian worship at this time, was Catholic. In 1518, the priest Matthew Zell arrived and began preaching the message of Reformation following Luther's vision. Strasbourg was an open-minded and tolerant city that welcomed diverse beliefs, and Zell's sermons were well-received.

Katharina soon converted to the Lutheran vision and became convinced that God wanted her to marry Matthew Zell "as an expression of her faith in God and her love for others" (Stjerna, 112, quoting McKee). Clerical marriage was forbidden by the medieval Church, and this policy had been condemned by Luther in his The Estate of Marriage (1522) in which he argued that celibacy was unnatural, harmful, and unbiblical. Although Luther himself had not yet married, he encouraged clerical marriage as another step in moving away from what he saw as the unbiblical and corrupt teachings of the Catholic Church.

Marriage between clergy was considered heretical at this time as was a layperson marrying a clergyman. Martin Luther's marriage to Katharina von Bora (l. 1499-1552), a former nun, would not happen until 1525, and Katharina's marriage to Matthew Zell was one of the first of its kind. Even though Strasbourg was a liberally-minded city, it was not yet so tolerant that this kind of event would pass unnoticed or without censure. Katharina married Matthew Zell on 3 December 1523 at 6:00 in the morning (as Stjerna, notes, to avoid drawing a crowd). The ceremony was officiated by their friend Martin Bucer, and afterwards, the couple celebrated the Eucharist by taking both the bread and the wine, a practice known as utraquism (Latin for "under both kinds"), which was forbidden by the Church; the wine was for clergy only, the bread for laypeople. In taking both, the Zells were announcing, along with their marriage, their stand for the Reformed vision of Christianity.

Defending Clerical Marriage

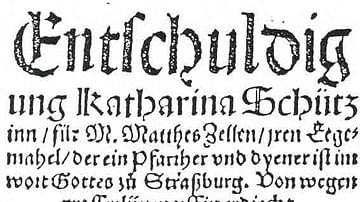

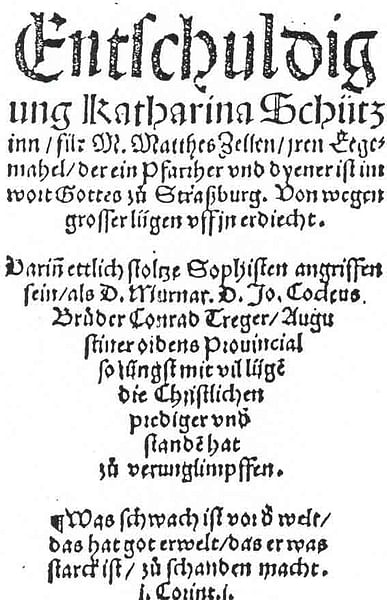

Although Matthew Zell retained his position, the marriage was criticized as heretical and scandalous. Strasbourg was a lucrative publishing center, and religious writings, especially since the Reformation movement started, were popular reading. Anyone who could write could have their work published, and pamphlets denouncing the Zells' marriage began to circulate. In response, Katharina wrote and published her Defending Clerical Marriage, the full title of which is translated as Katharina Schütz's Apologia for Master Matthew Zell, Her Husband, Who is a Pastor and Servant of the Word of God in Strasbourg, because of the great lies invented about him. Her open letter, published as a pamphlet, became a bestseller.

The work begins by noting the unbiblical policy of the Church against clerical marriage and explains the real reason for it: that the Church would lose money if they allowed clergy to marry since, by prohibiting marriage, they could charge clergy a tax on keeping prostitutes and concubines, as many did. The priesthood, she pointed out, was not celibate but was kept in a state of bondage by the Church, which extracted annual fees from them for the women they kept and, according to Zell, circulated amongst themselves. She advocated for honest marriages, recognized as legally binding, which would end the corrupt practice of the tax and allow for more sincere engagement by the clergy in preaching the gospel. She writes:

If the priests could honorably marry, they could preach from the pulpit more effectively against adultery. Otherwise, how can they condemn that in which they themselves are stuck. Watch over me, and I will watch over you. If, however, a priest had a wife, and if he did something bad, people would know how to punish him…For the prohibition against marriage comes from the Devil alone, but marriage comes from God, as the Holy Ghost says in the letter to Timothy. (Brady, 22)

Zell's piece was largely ignored or condemned, even though it was widely read and received quiet approval from Luther, but the negative reaction did nothing to keep her from publishing further. She would continue to write for the rest of her life, though only five of her works were published and most of her writings were personal correspondence. She regarded writing as another aspect of her calling to minister to people, regardless of their religious views or how closely those aligned with her own.

Ministry of the Open Door

Matthew and Katharina maintained an open-door policy at their home, welcoming refugees fleeing from religious persecution elsewhere as well as reformers visiting the city, the poor and needy, and those displaced by the German Peasants' War (1524-1525). The couple also visited the warring factions, advocating for peace. Scholar Rebecca VanDoodewaard comments:

During the Peasants' War, Katharina accompanied her husband and other ministers in visiting the camps to plead with people to stop the violence; their advice went unheeded, and three thousand more refugees poured into Strasbourg, which had a population of only about twenty-five thousand. Katharina was continually busy caring for such refugees. When she could not help, she recruited others…Katharina was also a regular visitor to the local prison; the inmates' religious views varied, but she spoke with many who spent time there. Her compassion for the men led her to make time for these visits despite her demanding schedule that could easily have crowded them out. (19)

Like Katharina von Bora, Anna Reinhart (l. c. 1484-1538, Zwingli's wife), and others, Katharina Zell also entertained visiting reformers and friends of the couple while maintaining her home, writing, and supporting her husband's ministry. The couple had hoped to also have their own family, but neither of their children lived very long. Their first child, born in 1526, died a year later, and they lost their second child in the early 1530s. Zell interpreted their deaths as a test of her faith and committed herself further to her ministry, adopting anyone who came to her. Scholar Kirsi Stjerna writes:

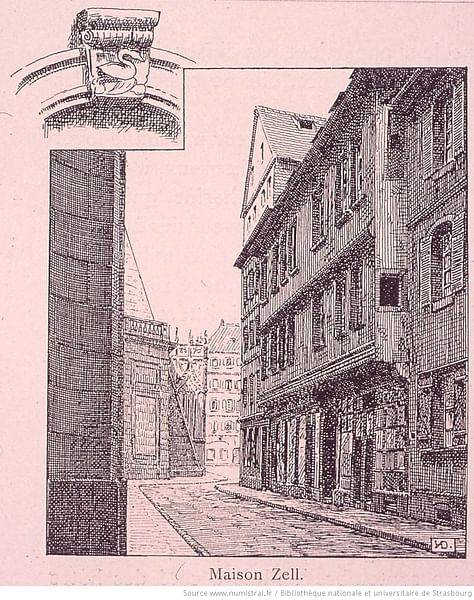

The Zells set an example in Strasbourg, like the Luthers in Wittenberg, for a Protestant parsonage. The Zells provided the model for a parsonage with an open-door policy and endless hospitality, in the spirit of the Luthers: they opened their house to everybody, ready to feed and offer shelter and, on the side, 'argue cordially with those who had not yet come to understand the absoluteness of Christ and faith alone.' Their parsonage was open for theologians on the road (including Calvin at one point) as well as refugees and those suffering from poverty or illness; at one time, they played host to a large group of soldiers trapped in the city…Their house of theology and refuge became famous for the indiscriminate hospitality, humanitarian care, and peaceful mediating over theological disputes to be found within its walls. The Zells' ecumenical and charitable spirit enabled them to host, entertain, debate with, and care for a colorful mix of personalities. (115)

As busy as she was, she still made time to write, carrying on correspondences, counseling, and offering her insights into the Bible. As important as her other work was, she is remembered today for her writings.

Written Works

From her first publication to her last, Zell inspired others, especially women, to embrace the Protestant vision and advocate for it as zealously as any man. She is thought to have inspired the French theologian and pamphleteer Marie Dentière (l. c. 1495-1561) after the latter had left her convent and fled to Strasbourg in 1524. Zell's Defending Clerical Marriage is cited by Stjerna as a possible influence on Marie Dentière's A Very Useful Epistle (1539) as well as her earlier work, The War and Deliverance of the City of Geneva (1536). Between 1534 and 1536, Zell also published a four-volume book of hymns (which she did not write, only collected) that became popular and to which she seems to have contributed the musical annotation.

The plague struck Strasbourg in 1541, and she consistently cared for the sick, including her husband, while continuing with her regular ministry and her writing. When Matthew Zell died in 1548, she delivered her Lament and Exhortation of Katharina Zell to the People at the Grave of Master Matthew Zell. This was another open letter that became popular reading and was inspired by her husband's last request that she encourage people to embrace the vision of Christ instead of persecuting each other over sectarian differences. Martin Bucer presided over the funeral but, shortly after, left Strasbourg for England, leaving Ludwig Rabus as the central ecclesiastical authority in the city and Matthew Zell's successor.

Rabus would be the inspiration for another of Katharina Zell's best-known works, A Letter to the Whole Citizenship of the City of Strasbourg from Katharina Zell, Widow of the (Now Blessed) Matthew Zell, The Former and First Preacher of the Gospel in This City, Concerning Mr. Ludwig Rabus, Now a Preacher of the City of Ulm, Together With Two Letters, Hers and His (1558). A subtitle to the work encourages a fair reading of both sides of the controversy, stating, May Many Read These and Judge Without Favor or Hate but Alone Take to Heart the Truth. Also a Healthy Answer to Each Article of His Letter. This work, along with her publication on the Book of Psalms, would be among her last.

Rabus Controversy

The occasion for A Letter to the Whole Citizenship of the City of Strasbourg was the public attack on Zell by someone she thought of as an adopted son, Ludwig Rabus, who had lived in the Zells' house and learned from both Katharina and Matthew. Rabus came from a poor family and was taken in by the Zells when he arrived in Strasbourg and could not afford food or lodging. The couple supported him until he left to attend the University of Tübingen 1538-1543, after which he returned, again living with the Zells, and became Matthew's assistant pastor. When Matthew died in 1548, Rabus was named his successor.

Among the many refugees and theologians who stayed with the Zells was Caspar Schwenkfeld (l. c. 1490-1561), who was originally a Lutheran before embracing the views of the anti-Lutheran theologians Thomas Müntzer (l. c. 1489-1525) and Andreas Karlstadt (l. 1486-1541), both of whom had been early advocates of the Lutheran vision. Schwenkfeld followed Müntzer's spiritualism, inspired by the mystic Meister Eckhart (l. c. 1260 to c. 1328), which claimed God communicated with believers through dreams and visions and the Bible was not the sole spiritual authority. Like Müntzer and Karlstadt, Schwenkfeld was rejected by Luther and mainstream Lutherans, and he and his followers were persecuted by the Reformed Church of the Zwinglians and the Anabaptists as well. He was welcomed at the Zell house, however, and treated kindly by Katharina.

When Rabus took over from Matthew, he began preaching against religious tolerance until he lost his position after Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, imposed the Augsburg Interim of 1548, which decreed a return to Catholic policies and teachings. Rabus remained in Strasbourg, continuing to preach a conservative Lutheran doctrine that condemned not only Catholicism but all other Protestant sects until he left (most likely due to a lack of support) and took a position in the city of Ulm. Katharina wrote to him at Ulm, asking why he had left, but her letter was returned unopened along with one from him denouncing her for encouraging heretics like Schwenkfeld, welcoming all kinds of other heretics into her home, and condemning her as a troublemaker who disturbed the peace by meddling in affairs that were properly the concern of men. Katharina responded, in part, writing:

Do you call this disturbing the peace that, instead of spending my time in frivolous amusements, I have visited the plague infested and carried out the dead? I have visited those in prison and under sentence of death. Often, for three days and nights, I have neither eaten nor slept. I have never mounted the pulpit, but I have done more than any minister in visiting those in ministry. Is this disturbing the peace of the church? (VanDoodewaard, 22)

Throughout the work, as she answered RabusI charges, she continued to advocate for religious tolerance, acceptance of others, and sincere devotion to Christian service and, as she had in all in writings, made no apologies for being a woman assuming a role of authority by instructing a man. Rabus never responded to her letter, but it became, and remains, one of her most popular.

Conclusion

Katharina Schütz-Zell continued writing until her health began to fail. In one of her last letters, she expressed no regrets and looked forward to her release from the body and welcome in paradise:

I see before my eyes and welcome the time of my release. I rejoice in it and know that to die here will be my gain, that I lay aside the mortal and perishable and put on the everlasting immortal and imperishable. (VanDoodewaard, 23)

Zell never claimed for herself any authority that was not given by scripture. She respected those passages, such as I Timothy 2:12, that prohibited women from preaching or having authority over men but, like Argula von Grumbach (l. 1490 to c. 1564) refused to remain silent in the face of injustice and inequality. Stjerna comments:

Of all the Reformation women, Katharina Schütz Zell stands out as extraordinary. Thriving in her role as her pastor-husband's "helper", she developed her own calling as a church mother with duties fitting to her personality, learning, and passion. Her vocation was shaped by her gender, to a degree, and by her context: she responded as a woman to the needs of the people in her town. Indiscriminate in her Christian compassion and willingness to care pastorally for those in need, she was a mediating voice between disagreeing theological voices, seeking for unity and peace for the sake of the gospel. (130)

Although her written works were ignored by many in positions of authority in her time, they spoke to the people as evidenced by their apparent popularity. The date of her death and the site of her grave are unknown, but, beginning in the 19th century, her voice again began to find an audience, and today she is recognized as one of the most courageous and committed of the early activists of the Protestant Reformation.