King Arthur is among the most famous literary characters of all time. The Arthurian legend of the Knights of the Round Table, Camelot, the Quest for the Holy Grail, the love affair of Lancelot and Guinevere, and the wizard Merlin have informed and inspired literary, musical, and other major artistic visions for centuries. There have been countless books, major films, operas, television shows, games, toys, plays, and graphic novels either re-telling or inspired by the Arthurian legend which developed in Europe between 1136-1485 CE, was revived in the 19th century CE, and remains popular in the present day.

The great legendary king is most likely based on an actual historical figure from the 5th or 6th centuries CE. The difficulty in identifying Arthur as a certain historical figure is due to the primary sources which first tell his story.

There are early histories which give accounts of the Briton victory over the Saxons at the Battle of Badon Hill - an event closely associated with Arthur - but do not identify the leader of the Britons as Arthur. The figure of Ambrosius Aurelianus is given in the earliest sources and this would make Ambrosius the best candidate for the historical Arthur except that other sources cite someone named Arthur as Ambrosius' war-chief. It is generally agreed that the legendary Arthur was based on an actual figure but who he might have been is unclear. The most reasonable understanding is that the legendary Arthur is based on a great historical warrior named Arthur.

The Historical Background

The claim that the legendary Arthur is based on an actual person is supported by the fact that 'Arthur' is a Welsh name derived from the Roman family name Artorius. The figure of Ambrosius Aurelianus, it is argued, could have had the given name Artorius. Roman names had become common in Britain since the conquest under Claudius in 43 CE.

Rome began withdrawing troops in the 3rd century CE to protect the empire from invading barbarians. These difficulties had been increasing in severity for around 200 years by the time of the 5th century CE and Rome had been steadily decreasing its garrisons in Britain as troops were needed on the continent. By 410 CE, the same year the Goths sacked Rome, all the Roman garrisons had been withdrawn from Britain.

Rome's decision to remove the troops left the people of Britain helpless against invaders. The Roman army stationed along Hadrian's Wall and other areas had been the Britons' protectors for over 300 years by this time. With the power of Rome withdrawn, the northern Picts and Scots saw their opportunity and commenced raids on British farms and villages.

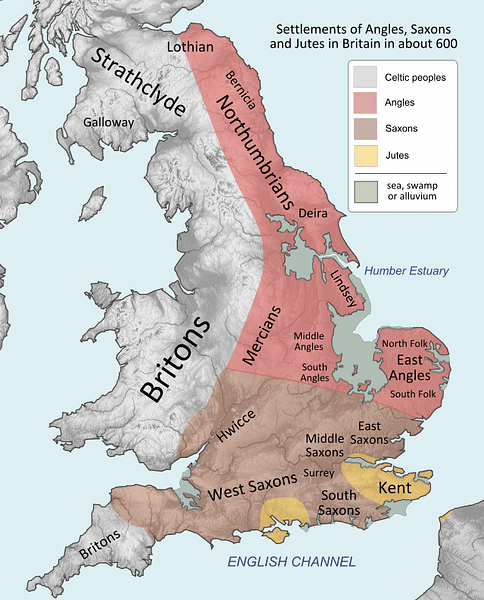

At about this same time, the Saxon confederacy broke apart on the continent and Saxon immigrants and raiders began appearing on the south-east coast of Britain. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles record:

A.D. 443. This year sent the Britons over sea to Rome, and begged assistance against the Picts; but they had none, for the Romans were at war with Attila, king of the Huns. Then sent they to the Angles, and requested the same from the nobles of that nation.

When no help came from Rome, a British king named Vortigern invited the Saxons to bring a military force to repel the Picts and Scots. The Saxons agreed but, once they had defeated the invaders, decided to stay. According to the historians Gildas (c. 500-570 CE), Bede (672-735 CE) and Nennius (9th century CE) – as well as many others – the Saxon immigration was an invasion (a claim disputed by modern scholars) in which Britain was sacked and looted continually.

At this time a great British leader appeared, rallied the people around him, and defeated the Saxons at the Battle of Badon Hill. This hero is called Ambrosius Aurelianus, by Gildas and Bede, and Arthur by Nennius, who is the first historian to mention his name. Arthur already seems to have been well known before Nennius' work. The Welsh poem Y Goddodin, an elegy for the warriors who fell at the Battle of Catraeth in 600 CE, refers to him by name as a great hero. Although extant manuscripts date only from the 13th century CE, the work is thought to have been composed shortly after the battle.

It is clear from the preface to History of the Kings of Britain by Geoffrey of Monmouth (c. 1100 - c. 1155 CE) that Arthur was regarded as a great king by his time; but Geoffrey's work would elevate him to mythical status.

The Arthurian Legend

Geoffrey of Monmouth is known as the Father of the Arthurian Legend for developing the character of King Arthur, adding mythical elements to his story, and introducing many of the central characters and motifs which would later be expanded upon by other writers.

The phrase Arthurian Legend encompasses a number of different versions of the tale but, in the present day, mainly refers to the English work of Sir Thomas Malory, Le Morte D'Arthur (Death of Arthur) published by William Caxton in 1485 CE. The legend developed from History of The Kings of Britain, passing over to France, to Germany, to Spain and Portugal, and back to England with numerous additions and versions proliferating, until Malory compiled, edited, revised, and rewrote a prose version in 1469 CE while he was in prison

The basic story goes that, once upon a time, there was a wizard named Merlin who arranged for a mighty king named Uther Pendragon to sleep with a queen named Igrayne who was another king's wife. Merlin's stipulation was that, when the child of their union was born, it would be given to him. All of this happens as it should, the child is named Arthur, and he is given to another lord, Sir Hector, to raise with his own son Kay. Many years later, when Arthur is grown, he accompanies Kay and Hector to a tournament in which Kay is to compete, finds that he forgot Kay's sword at home, and so takes one he finds in the forest stuck in a stone. This is the Sword in the Stone which can only be drawn from the rock by the true king of Britain.

Merlin returns at this point to explain the situation to Arthur, who had no idea he was adopted, and helps him fight the other lords who contest his claim to the throne. Although the Sword in the Stone is frequently associated with the famous weapon Excalibur, they are two different swords. The sword Arthur draws from the stone is broken in a fight with Sir Pellinore and Merlin brings Arthur to a mystical body of water where the Lady of the Lake gives him Excalibur.

Excalibur is more than just a sword; it is a symbol of Arthur's greatness. In some versions of the legend Arthur gives the sword to Sir Gawain but, in most, it is exclusively Arthur's. This is in keeping with many ancient tales and legends in which a great hero has some kind of magical weapon. Once Arthur has forced the other lords to recognize his legitimacy, he marries the beautiful queen Guinevere and sets up his court at Camelot.

He invites the greatest knights of the realm to come and dine in his banquet hall but, when they do, they begin fighting over who will get the best seat. Arthur severely punishes the knight who began the trouble and, to avert any repeat in the future, accepts a round table from his father-in-law. From this time on, he explains, everyone sitting at the table will be equal, including himself, and everyone's opinions will be weighed seriously no matter their social standing. Further, anyone requiring assistance will be welcomed in the hall to request it and every wrong shall be righted by Arthur and his knights.

The motif of the Round Table, along with the magical weapon, sets Arthur above the kings who have preceded him who believed that their position of power dictated what was right or wrong; Arthur believes that everyone's opinion is valid and that might should be used to support right, not define it. Arthur again sends out invitations to noble knights to join him but this time his messengers are to go even farther, beyond the boundaries of Britain.

Among the knights who answer his call is Lancelot of the Lake, a French knight who is unrivaled in combat. He and Arthur become friends at the same time that he falls in love with Guinevere and she with him. While this affair is going on behind the scenes, the Knights of the Round Table are engaging in all kinds of fantastic adventures. If there is no apparent adventure, Arthur will go off and find one. In the famous story of Gawain and the Green Knight, a challenger comes to court to start the adventure. In the story of Jaufre (also known as Girflet) he arrives at the court to be knighted and then proceeds on his own adventures before returning and involving the others.

The greatest adventure the knights undertake is the quest for the Holy Grail. The grail is originally a platter in the French version of the legend or cauldron in the Welsh. It is transformed, however, into the cup of Christ used at the Last Supper by the time Malory revises the story and this is how it is generally understood. The grail quest can only be completed by a knight pure of heart and this is finally accomplished by Galahad, son of Lancelot.

Throughout all these adventures there are a number of times Guinevere is kidnapped by some menacing lord and has to be rescued or other ladies are in distress and also need the assistance of a noble knight. There are dragons, giants, invisible spirits, sacred wells, unending waters to cross, inanimate objects which move and speak, courageous heroes, scheming villains, women who are beautiful and noble and others whose beauty conceals their devious nature. Encountering all of these, Arthur remains a good and noble king until the affair of his queen and best friend is revealed by Arthur's illegitimate son Mordred who then challenges Arthur's right to rule.

In the final battle between Mordred and Arthur, Mordred is killed and Arthur mortally wounded. Guinevere retires to a convent and Lancelot to a hermitage. All of the other great knights of the court are killed. Sir Bedevere helps Arthur from the field and returns Excalibur to the Lady of the Lake. Once the sword has been returned, Arthur dies and is carried away on a ship to the isle of Avalon.

The Legend as Allegory

The story of King Arthur and his knights instantly resonated among the literate in the Middle Ages shortly after Geoffrey published his work in 1136 CE. By c. 1160 CE the Norman poet Wace had translated it into Old French vernacular and the great poet of Provence, Chretien de Troyes (c. 1130-c.1190 CE) expanded upon it in his works. The legend was deepened and broadened by other French poets, re-worked and added to by German writers, and then translated to English by the cleric Layamon (12th/13th century CE). It was then revised in English prose as the Vulgate Cycle (1215-1235 CE) which was edited into the version known as the Post-Vulgate Cycle (c. 1240-1250 CE), the main source Malory worked from in 1469 CE.

One of the most enduring motifs of the legend is that of the Damsel in Distress who must be rescued by a noble knight who then, in many stories, marries her. It has been pointed out that the Arthurian legend, from the time of Chretien de Troyes onward, elevated the status and power of women. Even the damsel in distress often turns out to be a queen who possesses great wealth, land, or magical items. This is a significant departure from the literature of the Middle Ages in which women are usually depicted as objects to be fought over or protected.

It has been suggested that the legends are Christian allegories which symbolically represent a believer's journey of faith. The quest for the Holy Grail, for example, exemplifies the Christian path: one must be pure of heart to complete it but, even if one is not, the life of the participant is still improved through the attempt. It has also been claimed that the legends are mystical allegories. Scholar David Livingstone advances this view in claiming that the Arthurian legends are "Kabbalistic allegories of the trials and perils that beset the mystic on his journey towards a mystical union with God" (317). Most interpretations agree on a Christian foundation for the tales and the use of Christian symbols to advance it.

A lesser known theory suggests that they are based on a Christian heresy known as Catharism which flourished in the 12th and 13th centuries CE in southern France. The Cathars (from the Greek Catharoi, pure ones) venerated a female deity Sophia (wisdom in Greek) whose worship was compatible with the Medieval veneration of the Virgin Mary; the sacrifice of Christ, as the dying and reviving god, also fit with their beliefs. The Cathars emphasized purity of spirit and nobility in action and the sincerity of their faith, when compared with the corruption of the Catholic Church, brought them a number of converts until the church launched the Albigensian Crusade and massacred them between 1209-1244 CE.

The theory, most famously expressed by the scholar Denis de Rougemont in his Love in the Western World, is that the French poets – most notably Chretien – disguised the Cathar faith in romantic tales. Chretien was a poet at the court of Marie de Champagne, daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine, both known for their defiance of church doctrine and both associated with southern France and the Cathar heresy. According to this view, Guinevere's numerous abductions would represent the church trying to appropriate Sophia, the ancient wisdom, and her rescue would symbolize the Cathars taking her back. The Damsel in Distress, likewise, would be this same Sophia who needs to be rescued by a Cathar perfecti (a “perfect one”) who then “marries” her and receives her gifts.

The obvious Christian imagery and symbolism of the legend would seem to contradict this view – and perhaps it does – but there are a number of interesting aspects which might support it. Among these is the fact that women were not presented in this same way in earlier European Christian literature. The concept of a love one would sacrifice for, cannot live without, and would even die for is central to the Arthurian Romances as it was to a Cathar's relationship with Sophia. The development of the concept of Courtly Love, chivalry, and the elevation of women in southern France, the region most closely associated with the Cathars, is another suggestive aspect.

Since the Cathars were unable to express their ideas openly because of the persecution of the church, they embedded their message in poetry which was interpreted by non-initiates at face value and introduced Medieval Europe to the prototype of the modern-day love song. The uninformed, to use de Rougemont's expression, responded to the surface message of the legend without recognizing the spiritual power of the symbols.

Legacy

The legacy of the Arthurian legends is so pervasive that it touches every aspect of world culture. The quest for spiritual answers, the noble defender of the weak, the purity of romantic love, the importance of fidelity, freedom, justice, and equality, a fair and responsive government, and a good and noble leader, all of these aspects of the legend have affected people's interpretation of the world around them for centuries. Further, the modern understanding of romantic relationships is directly or indirectly influenced by Arthurian motifs.

Literature and art, especially, have been influenced by the Arthurian legends through the many different translations of the work and the others which were inspired by it. The legend fell out of favor during the Renaissance but was revived by Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892 CE) through his Idylls of the King, published in 1859 CE. Tennyson's work inspired others and revived an interest in the story of King Arthur and his noble knights, the Round Table, and a world of magical wonder and spiritual meaning.

In the enchanted lands of the Arthurian realm anything can happen, at any time, but goodness will always triumph over evil and darkness can never put out the light. Help always comes for the hero or the damsel, the wicked are punished, the good are rewarded, the injured are healed, and justice is always recognized and rewarded. Even in defeat, the right prevails and, after countless struggles, the knight and damsel ride away toward a long life of contentment.

Although there is undeniably a great deal of religious and spiritual symbolism in the tales, the legend has never needed any allegorical interpretation to explain its popularity. It offers a vision in which, for the most part, people's lives work out for the best and, even in the tragic fall of Arthur and his knights, one can find meaning and purpose. This is the reason for the legend's enduring popularity in every age which responds to it: a reprieve from a world that often lacks magic or apparent meaning and where most people do not live happily ever after.