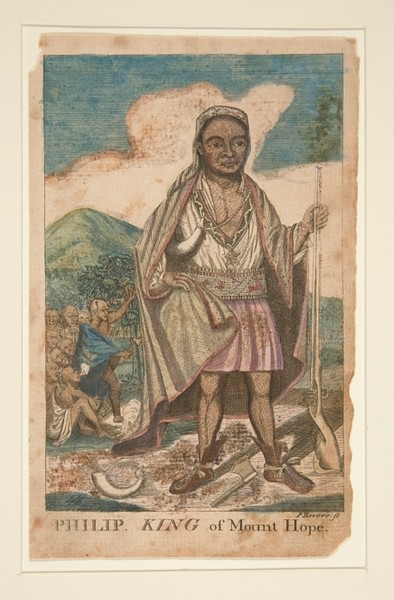

Metacomet (also known as King Philip and Metacom, l. 1638-1676) was chief of the Wampanoag Confederacy between 1662-1676, best known as the leader of Native American forces during the conflict known as King Philip’s War (1675-1678) during which the Wampanoags and their allies fought the English immigrants in an effort to preserve their land and way of life.

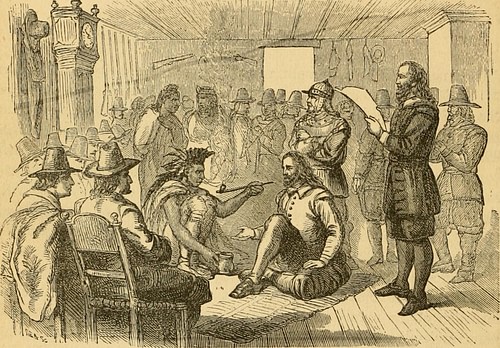

Metacomet’s father, Massasoit (l. c. 1581-1661) was the chief who had first welcomed and helped the pilgrims of Plymouth Colony in 1621 and had signed the Pilgrim-Wampanoag Peace Treaty with the first Plymouth governor John Carver (l. 1584-1621) on 22 March of that year. The treaty remained unbroken during Massasoit’s lifetime, but after his death, relations between the colonists and natives began to unravel.

Massasoit was succeeded by his eldest son Wamsutta (l. c. 1634-1662, also known as Alexander Pokanoket). In an effort to strengthen ties between his people and the English, Massasoit had his sons renamed, with their consent, by the English of Plymouth and so Wamsutta was known as Alexander and Metacomet as Philip. Wamsutta died in 1662 shortly after a meeting with assistant governor Josiah Winslow (l. c. 1628-1680), and Metacomet claimed he had been poisoned. His claim had grounds as Winslow was hostile to the natives and saw them as obstacles who needed to be removed to make way for the English. When three Wampanoag men, all counselors to Metacomet, were hanged by the English for the murder of a Christian native, Metacomet felt he had endured enough, and King Philip’s War began in June 1675.

The war devastated the region of New England, killing thousands and destroying both English settlements and native villages and forts. Metacomet was betrayed and assassinated by a Christian native who served the English on 12 August 1676 and his followers abandoned the war effort. There were other tribes who continued the war to the north and south of Metacomet’s central theatre of operations, but they finally surrendered in 1678, ending the war. Afterwards, the leaders of the native army were executed and many others sold into slavery. Those not enslaved or killed either merged with other tribes, left the region, or were confined to reservations. King Philip’s War completely changed the power dynamic of New England and set the policies in place which would direct colonial interaction with the natives for the next 100 years and, after the United States was founded, even further up through the 20th century.

Early Life & Plymouth Colony

Metacomet was born when the English had been in the land for 18 years and grew up only knowing the tension and conflict between the immigrants and his indigenous people. Plymouth Colony had been established in 1620, and his father, Massasoit, had chosen to help them survive, sending Squanto (also known as Tisquantum, l. c. 1585-1622 CE) to teach them how to plant crops, hunt, and fish. The success of the Plymouth Colony encouraged further English colonization between 1620-1628, with the largest group, of 700 Puritans, arriving in 1630 under the leadership of John Winthrop (l. c. 1588-1649) to develop the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Massasoit and John Carver of Plymouth had signed a peace treaty in March of 1621 which continued to be honored, but no such agreement had been forged between Massachusetts Bay and the natives. Winthrop orchestrated trade agreements, which assumed peaceful relations, but these were not actual treaties. Winthrop believed that God had ordained the English to colonize North America and cited the many empty Native American villages – depopulated by European diseases which killed up to 80% of the coastal population – as proof of God’s plan in that he had "removed the Indians" to make way for the Puritans.

Metacomet was born the same year the Pequot War – fought between Massachusetts Bay with colonial and Native American allies against the Pequot tribe – ended in a colonial victory. The Pequots were dispersed, either sold into slavery or pushed onto a reservation. With the Pequot out of the way, the English occupied their lands along the Connecticut River and continued to expand from there.

Expansion & Conflict

Massasoit had kept the Wampanoag Confederacy out of the Pequot War and maintained the friendly relations he had forged with Plymouth Colony. Colonist and later governor Edward Winslow (l. 1595-1655) had saved Massasoit’s life years before, as well as a number of his tribe, when illness struck, and both parties had benefited from the 1621 treaty. The Pequots and their troubles were none of Massasoit’s concern as he had an agreement with Plymouth that they would not intrude upon his territory which stretched from modern-day Rhode Island (around Warren) down through Massachusetts.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony, however, had no such agreement with Massasoit and, while they had yet to threaten Wampanoag land, they drew nearer as they took land from other tribes. Scholar Alan Taylor comments:

As the colonists made the land more familiar and profitable to themselves, they rendered it more alien and hostile to the Indians. By clearing the forest, the colonists steadily eliminated the habitat for the wild animals and plants critical to the Indians’ diet and clothing. The settlers also introduced pigs and cattle that ranged far and wide, beyond settler properties, into the forest and the Indian cornfields. In 1642, the Narragansett chief Miantonomi complained:

You know our fathers had plenty of deer…and our coves [were] full of fish and fowl. But these English have gotten our land, they with scythes cut down the grass and with axes fell the trees; their cows and horses eat the grass, and their hogs spoil our clam banks, and we shall be starved.

When the Indians reacted by killing and eating the offending livestock, the colonists demanded that the culprits stand trial in their courts for theft. Insistent on their own property rights in animals, the New English were indifferent to the Indians’ property rights in their growing corn. (193)

There were no large-scale armed conflicts following the Pequot War but plenty of disagreements as the English expanded further, disregarding Native American claims, customs, and culture. The situation grew worse for the natives as more and more colonists continued to arrive and demanded more land for settlements.

Death of Massasoit & Wamsutta

Toward the end of his life, Massasoit wished to make a gesture which would ensure continued bonds of friendship between the Wampanoag and Plymouth and so he consulted with his sons and then sent Wamsutta to Plymouth to request that he and Metacomet be given English names. In Wampanoag culture, as with many indigenous tribes, one took a new name at a significant turning point in one’s life and, in this case, it was Wamsutta assuming leadership of the confederacy. Wamsutta was given the name Alexander and Metacomet was called Philip to honor Philip II of Macedon and his son Alexander the Great.

Massasoit died of natural causes in 1661 and Wamsutta became chief. He had married Weetamoo (l. c. 1635-1676), daughter of the chief Corbitant and of high status, c. 1653 and may have had a child at the time he became chief. In 1662, Wamsutta was summoned to the Plymouth court to give an account of himself on charges of illegal land sales. Assistant governor Josiah Winslow, son of the man who had saved Wamsutta’s father’s life, was the immediate authority acting either on his own initiative or by orders of then-governor Thomas Pence (l. c. 1601-1673). Winslow was among the second-generation Plymouth colonists who had forgotten or ignored the vital aid given to their parents by the Wampanoags in establishing the colony. Scholar Nathaniel Philbrick elaborates:

By the 1660s, the English no longer felt that their survival depended on the support of the Indians; instead, many colonists, particularly the younger ones, saw the Indians as an impediment to their future prosperity. No longer mindful of the debt they owed the Pokanokets, without whom their parents would never have endured their first year in America, some of the Pilgrims’ children were less willing to treat Native leaders with the tolerance and respect their parents had once afforded Massasoit. (200-201)

Wamsutta had sold land to one Richard Smith of Rhode Island and, since the English colonies each considered themselves God’s people and only entered into agreements that benefited themselves, sale of land to another colony, by a native chief allied with Plymouth, was considered illegal. Wamsutta seems to have been aided in his land sales by his friend and brother-in-law, the English trader Thomas Willet (l. 1605-1674), who spoke Dutch and Algonquian and frequently acted as interpreter. Wamsutta was questioned and released after being provided with refreshment and died shortly after returning to his village. Metacomet now became chief, but relations with Plymouth were tense from the start as he claimed his brother had been poisoned by the English, specifically by Winslow.

Winslow, Willet, & Land Sales

Metacomet now began to use the title and name King Philip in his interactions not only with the colonists but his own people and dressed accordingly. Philbrick writes:

By all accounts, Philip looked the part. One admiring Englishman who saw the [chief] on the streets of Boston estimated his clothing and large belts of wampum to be worth at least 20 pounds sterling, approximately $4,000.00 today. (209)

He had acquired his money through the fur trade and land sales but understood now he had to preserve the lands for the good of his people. He had his secretary and interpreter, John Sossamon, write up a letter to Governor Pence c. 1662 placing an embargo on land sales for seven years. Pressure from the English, and his own financial needs, however, forced him to agree to a sale in 1664. In 1665, the English interfered with a ritual execution he was presiding over on Nantucket Island and in other ways seemed to disrespect the new chief.

In 1667, King Philip dictated his will to John Sossamon. Philip was married to Wootonekanuske, sister of Weetamoo, and they had recently had a son. Philip wanted to make sure the boy received his proper inheritance and wanted the will written in English. When Sossamon was done, Philip had him read the will back to him, and all seemed in order, but Sossamon had actually directed all of Philip’s land and valuables be left to himself. When Philip found out, he was naturally enraged and Sossamon fled the village and returned to his mentor, the Christian missionary John Eliot (l. c. 1604-1690). Philip blamed Sossamon’s treachery on the corrupting influence of Christianity.

Governor Pence died in 1673 and Josiah Winslow succeeded him. Philbrick notes, “by the time he became governor in 1673, Winslow had come to embody Plymouth’s policy of increasingly arrogant opportunism toward the colony’s Native Americans” (214). Willet, who pretended to be a friend to both the colonists and the Wampanoags, encouraged Philip to sell more lands in transactions which benefited Willet more than anyone else. Philbrick writes, "from 1650 to 1659, there had been a total of fourteen Indian deeds registered in Plymouth court; between 1665 and 1675, there would be seventy-six deeds" (214). These sales profited Winslow and Willet more than they did Philip or his people. When Winslow’s practices were noted as illegal, he used his office as governor to simply change the laws.

Sossamon & the Trial

Winslow continued his high-handed policies with the natives as Philip lost more and more land in Willet or Winslow negotiated deals. Winslow called in debts before they were due and forced the debtor to mortgage land and then used the mortgage to take even more land. Eventually, Philip began discussing an uprising with his tributary chiefs and a multifaced plan to drive the English from the region. His talks were overheard by John Sossamon who quickly ran to Winslow to report the potential uprising, expecting he would be handsomely rewarded. Winslow dismissed his report as untrustworthy. Scholar Jill Lepore describes the meeting and what happened next:

Winslow, alas, neither heeded Sossamon’s warnings nor assuaged his fears. And he spoke of no reward. Instead, the governor dismissed Sossamon’s information "because it had an Indian [origin] and one can hardly believe them [even] when they speak truth." He sent the minister on his way…Within a week of his meeting with Winslow, John Sossamon mysteriously disappeared. In February, his bloated, bruised body was found under the ice at Assawompset Pond. (21)

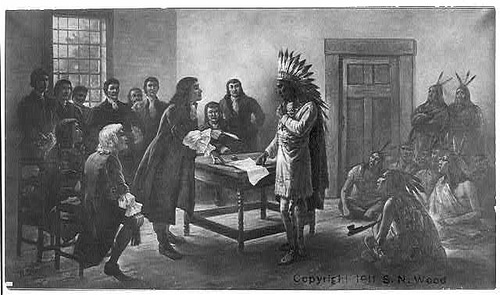

Philip was called before the court and interrogated regarding Sossamon’s murder and the rumors of the uprising and defended himself, denying the truth of Sossamon’s account and any involvement in his death. Winslow responded by ordering the Wampanoag to turn over their weapons which they, at least in part, complied with. On 1 March, the Plymouth court interrogated other Native Americans regarding Sossamon but was no closer to solving the murder than before. By 1 June, however, eyewitnesses suddenly appeared claiming Sossamon had been killed by three of Philip’s chief counselors: Mattashunannamo, Tobias, and Tobias’ son, Wampapaquan.

A jury was swiftly called comprised of 12 Englishmen and six natives. Without a doubt, Winslow could not have cared less about justice for the murdered native, but the trial went on anyway, and the three were convicted and then hanged on 8 June 1675. Three days later, the Wampanoags were in arms around Swansea Colony, and the colonies of Rhode Island, Massachusetts Bay, and Plymouth quickly sought negotiations with King Philip and the other chiefs but it was too late. On 24 June 1675, the Wampanoag attacked Swansea Colony and King Philip’s War had begun.

King Philip’s War

The war took the form of guerilla raids by Native American tribes and reprisals by the colonists. In early August, the natives destroyed the colony of Brookfield and in September ambushed and killed 57 out of a 79-man company at the Battle of Bloody Brook. The Narragansett tribe remained neutral but agreed to take in non-combatants of women and children as well as the wounded. Josiah Winslow accused them of aiding the enemy and, on 19 December 1675, led an attack on their stronghold, slaughtering over 600 Narragansetts as well as the women, children, and injured of other tribes. The Narragansetts then joined the war on Philip’s side.

Requiring greater numbers and more resources, Philip led his army into New York in early January 1676 to seek Mohawk help. The Mohawks had allied themselves with the English during the Pequot War and did so again, attacking Philip, killing many of his men, and driving him back to New England. He resolved to fight on alone and continued destroying settlements and killing colonists throughout the year with the aid of the Narragansett, Nipmuc, and other tribes.

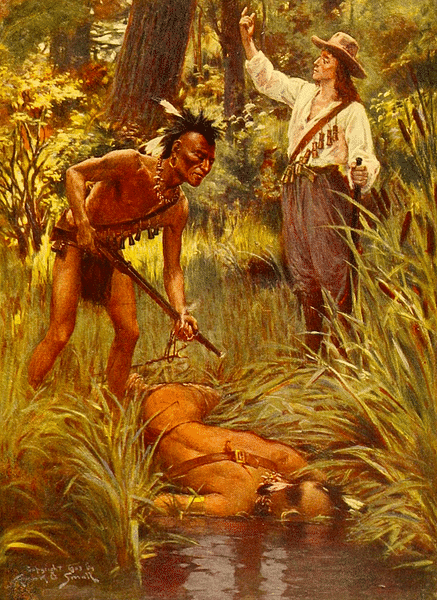

He was finally betrayed by a former counselor, John Alderman, who had converted to Christianity and become a "praying Indian" in service to the English. Alderman led Captain Benjamin Church (l. c. 1639-1718) and Josiah Standish (l. c. 1633-1690) to Philip’s camp at Mount Hope. Alderman shot Philip dead and his corpse was beheaded and hands cut off. Church gave these to Alderman as trophies and Alderman charged people to see the head until he finally sold it to Plymouth Colony for 30 shillings. The head remained on a pole outside the fort for the next 20 years.

Conclusion

Although the immediate cause of the war was the hanging of Philip’s counselors – in direct violation of the 1621 treaty which stipulated both parties would punish their own people for offenses – the conflict became inevitable once Winslow became governor and was free to act on his racist and genocidal policies. English land theft had been ongoing since the pilgrims landed at Pawtuxet in 1620 and occupied the site without compensating the Wampanoag and had only become more expansive and extensive with time.

Many colonists felt that the war was brought on by their poor treatment of the natives and God was punishing them for these sins, using Philip and his army as his instrument of justice. Even so, this guilt did nothing to encourage better treatment; they just held more fast days and days of repentance during which they asked God for help against the "scourge" they believed God himself had released upon them.

After Philip’s death, the war was won in central New England but continued in the north and south until 1678. Survivors, such as Philip’s wife and son, were sold into slavery, and Weetamoo, who had commanded her own force, was killed, mutilated, and had her head displayed at Taunton colony. Winslow had previously advanced a policy to regard all natives as guilty whether they had taken part in the war, declared neutrality, or even helped the English, and many more were sent as slaves to Bermuda and the West Indies.

Those that remained were pushed onto reservations and increasingly lost personal and civic rights. Many years later, the descendants of those who stole Native American land and enslaved them would name high schools, ships, and souvenir shops after King Philip but have yet to actually honor him by fully acknowledging their ancestors’ racialist policies leading up to, and away from, King Philip’s War which would later become standard US policy in dealing with Native American claims to even the most basic rights in the land which had formerly been theirs.