The Knight’s Revolt (1522-1523) was a military action led by the German imperial knight Franz von Sickingen (l. 1481-1523) and encouraged by the knight and writer Ulrich von Hutten (l. 1488-1523) launched to restore the status of the imperial knights and advance the Protestant Reformation in Germany. The revolt failed to rally the peasants and was quickly crushed.

Hutten was a poet-knight and Humanist who had already taken a stand against the abuses and corruption of the Church through satires and who saw in Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) a real hope of establishing a German Church and driving the Church of Rome from the land. Sickingen supported Luther, as a number of powerful nobles did, for several reasons which included the possibility of access to rich Church property, presently tax-free, that could benefit knights such as himself.

The imperial knights, once a powerful demographic, had lost both power and prestige owing to the increased wealth of the higher nobility, the decline of the feudal system, and advances in military technology which threatened to make the mounted, armored, warrior obsolete. Further, the 10% tithe demanded by the Church, as well as other fees, drained their treasuries and, because the peasants they relied upon for taxes were taxed by the Church and the higher nobility as well, they no longer commanded the wealth and status they once enjoyed.

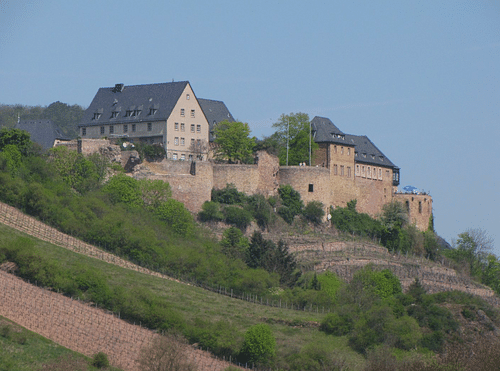

Sickingen launched the revolt in August 1522, while Hutten was in Switzerland trying to rally support, but failed to take the city of Trier when the peasants refused to support him. He retreated to Nanstein Castle at Landstuhl, pursued by the armies of Philip I of Hesse (l. 1504-1567), Elector Louis V, Count Palatine (l. 1478-1544), and the Archbishop of Trier, Richard von Greiffenklau (l. 1467-1532). Their superior firepower destroyed his defenses and he died of his wounds after surrendering on 7 May 1523. Hutten died a few months later in Switzerland from syphilis.

The knights who had followed or supported Sickingen had their lands confiscated by the higher nobility and were reduced to working for them while taxing the peasants at higher rates than before. The Knights’ Revolt (also known as the Poor Barons’ Rebellion) is therefore sometimes cited as a contributing cause of the German Peasants’ War (1524-1525) which was a revolt of the lowest class against abuses by those above them. Both revolts are frequently cited in connection with Luther whose defiance of the Church inspired others to challenge secular authority.

Cultural & Political Background

The Germanic territories at this time were part of the Holy Roman Empire which, like all of Europe, maintained the social structure of the Middle Ages with the emperor at the top followed by the higher nobles, then the lesser nobles (which included the imperial knights), then the clergy (who were almost all from families of nobles or lesser nobles), then the merchant class and, at the bottom, the peasants who were required to pay taxes to all of those above.

The Church provided the spiritual justification for this hierarchy through their claim that it was ordained by God. Challenging the social structure was therefore considered an affront to the Divine and biblical passages were cited to make sure everyone understood their place, such as Ephesians 6:5-9 which includes the line, “Servants, obey your earthly masters with respect and fear, and with sincerity of heart, just as you would obey Christ.” The nobles were clearly the masters and all who were below them were expected to bow to their authority.

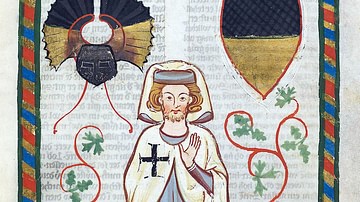

The imperial knights answered directly to the emperor, and many were as powerful as any prince or duke but, because they were not granted Imperial Estates (reserved for higher nobles), they lacked representation in the Imperial Diet (assembly) that passed the laws of the land. They answered directly to the emperor and were expected to raise and lead troops in his various causes. Knights were granted land, handed down within a family father-to-son, but these tracts were not as large or lucrative as the estates of nobles. Knights taxed their peasants but acquired real wealth by attacking nearby cities, carrying off important nobles, and holding them for ransom or even occupying the cities themselves until a ransom was paid.

Since they were not represented in the Imperial Diet, there was no way they could change the laws to improve their finances and, as the 16th century began, their power began to decline as the nobility’s wealth translated into greater influence and reach while, at the same time, the political power of the merchant class was on the rise. The knights had always been well-respected as formidable, mounted warriors but the development of the arquebus (musket) in the 15th century, with its ability to fire a bullet through armor, as well as the creation of the Wagenburg (wagon fort) threatened to make them obsolete. During the Hussite Wars (1419-c. 1434), the general Jan Zizka (l.c. 1360-1424) used both to neutralize knights in battle and this trend had continued.

In 1495, the knights had petitioned for inclusion in the Imperial Diet and presented a list of grievances to the assembly at Worms. The nobility refused to enact any of their protests as law except one making private warfare illegal – but only for the knights, not the nobles. This act deprived the knights of their major source of wealth as they were now prohibited from ransoming cities or capturing and ransoming nobility.

Luther & the Knights

Martin Luther’s 95 Theses, posted at Wittenberg in 1517 and popularized through 1519, presented an unimaginable opportunity for the knights to regain their former prestige. As the Reformation spread, the status quo of the traditional social hierarchy was challenged. Lesser nobles, including the knights, saw a chance to improve their fortunes by supporting Luther and seizing Catholic lands and assets for themselves. At the same time, however, this was a risky proposition not only because it was far from certain that Luther’s “new teachings” would actually result in any significant change but because the nobles had come to rely on the Church for their own gain. Supporting the Reformation was a gamble in which one might win more than one had or lose it all. Scholar Ronald G. Asch comments:

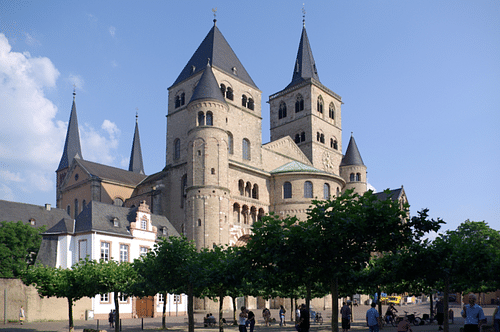

A certain reluctance to support the Reformation can partly be explained by the structure of the late medieval church. Many bishops and other high-ranking clerics were themselves nobles and the late medieval church has often been described as the “nobility’s almshouse.” After all, cathedral chapters, collegiate churches, monasteries, and convents offered a life of ease and prosperity to many younger sons and unmarried daughters of noble families. Higher positions at the head of a diocese or a rich abbey gave those who obtained them considerable secular power. In the Holy Roman Empire most bishops acted not only as spiritual shepherds of their flocks, a duty they normally used to take very lightly, but in addition, they also ruled vast secular dominions; three of them, The Archbishops of Cologne, Mainz, and Trier, were members of the exclusive college of prince electors who chose the new emperor when his predecessor had died. (Rublack, 566)

If Luther succeeded in dismantling the Church – and, in 1519/1520, this was not only far from Luther’s intentions but a seeming impossibility – then the nobility stood to lose power but, at the same time, by supporting his cause for reform, one might acquire more land through confiscation and therefore more wealth and greater power. This possibility appealed to a number of nobles and knights including, secretly, Philip I of Hesse, Frederick III (the Wise, l. 1463-1525, one of the electors), and, openly, Franz von Sickingen, and Ulrich von Hutten.

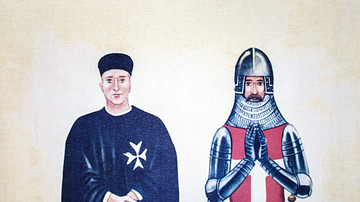

Sickingen & Hutten

Sickingen inherited Ebernburg Castle, in the town of Bad Munster am Stein-Ebernburg, from his father and, as a knight, fought for the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I (r. 1508-1519) in his wars with Venice. He was rewarded with lands along the Rhine River and modernized the 12th-century castle of Nanstein at Landstuhl with better defenses, making it one of the strongest fortresses in the region. From here and Ebernburg, he launched raids throughout the Rhineland “liberating” wealth in the name of the people which he then kept for himself. Scholar Roland H. Bainton comments:

Sickingen was trying to obviate the extinction of his class by giving to Germany a system of justice after the manner of Robin Hood. He announced himself as the vindicator of the oppressed and, since his troops lived off the land, he was always seeking more oppressed to vindicate. (125)

He defied the ban on private wars and relied on the old method of taking cities, lands, or people hostage and demanding a large ransom for their return, increasing his power steadily so that he was even able to compel a significant sum from Philip I of Hesse. In 1519, when Maximillian I died, Sickingen accepted bribes from France to support their candidate for Holy Roman Emperor then surrounded Frankfurt, where the election was taking place, and forced the election of the young Charles V instead; two years later, he invaded France.

He first met Hutten in c. 1517 when the latter appealed to the Swabian League for justice in the murder of his relative, Hans von Hutten, by Ulrich, Duke of Wurttemberg, and Sickingen saw an opportunity for booty. Hutten was a highly educated poet best known for his contributions to The Letters of Obscure Men, a collection of satirical works. He had been sent to a Benedictine monastery when he was ten years old by his father, where he learned Latin, but left after seven years for Cologne, immersing himself in the intellectual life of the city, before traveling on. He studied in Italy for the law, published poems, served in the military as a mercenary, and returned to Germany in 1517 where he was knighted for his literary works by Maximillian I.

During his travels, he had acquired an intense hatred for the Roman Catholic Church generally and the pope specifically. Hutten envisioned a united Germany without papal influence and the exorbitant tithes that drew wealth from Germanic peoples to be spent on lavish buildings in Rome. When Luther’s 95 Theses began attracting attention, Hutten dismissed them as more theological nonsense until he heard Luther defend his views at Augsburg in 1518. Hutten threw his support behind Luther, started printing anti-Catholic pamphlets, and then realized he could enlist Sickingen in the cause. Bainton comments:

Hutten established himself at Sickingen’s castle called the Ebernburg and there the poet Laureate of Germany read to the illiterate swordsman from the German works of the Wittenberg prophet. Sickingen’s foot and fist stamped assent, as he resolved to champion the poor and sufferers for the gospel. Popular pamphlets began to picture him as the vindicator of the peasants and of Martin Luther. (125)

Hutten corresponded with Luther, encouraging him, and Sickingen also openly sided with Luther’s cause. In 1519, Hutten wrote in defense of the Humanist scholar Johann Reuchlin (l. 1455-1522), great uncle of Luther’s right-hand man Philip Melanchthon (l. 1497-1560) when Reuchlin was threatened by the Dominican Inquisition for his defense of works in Hebrew. Sickingen supported Hutten and Reuchlin by threatening military intervention, quickly ending Reuchlin’s persecution. After Luther’s speech at the Diet of Worms in 1521, Sickingen offered him protection at Ebernburg Castle, but Luther had already accepted the offer of Frederick III and was taken to Wartburg Castle instead.

The Knights’ Revolt

Sickingen’s castles now became safe havens for those who supported the Reformation, including the future Reformer Martin Bucer (l. 1491-1551) who was invited to Ebernburg in early 1522. Sickingen and Hutten proposed a complete restructuring of society, after they had rid themselves of the Church, with the goal of creating a united and independent Germany. Sickingen encouraged his supporters to stop paying taxes to the nobility or tithes to the Church while Hutten continued publishing pamphlets and tracts popularizing Sickengen’s stand, appealing to the peasantry for support, defending Luther, and attacking the Church.

At some point in 1522, Hutten left to rally support in Switzerland among the followers of Reformer Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) while Sickingen called for an assembly under the name of the Brotherly Convention of Knights to take military action. He announced that their first target would be Richard von Greiffenklau, Archbishop of Trier, who had publicly denounced Luther (though, unknown to Sickingen, was corresponding with Luther to try to resolve their differences). Sickingen had pamphlets distributed encouraging the peasants of Trier to rise up against Greiffenklau and his declaration of war on the city made clear that his was a holy cause of liberation.

He justified the war by claiming the city had never paid a ransom due for two councilors captured but returned years before while, at the same time, announcing he was taking these measures in the name of the Emperor Charles V - who would never have actually supported a military action by a Reformed knight against a Catholic Archbishop. Sickingen counted on Luther’s support elsewhere in rallying a popular movement and that of the peasants of Trier who, he was sure, would open the gates upon his approach and so only brought enough gunpowder for his cannon for a week-long assault and does not seem to have thought he would even need that much.

The peasants of Trier, however, failed to mobilize as they knew Sickingen’s reputation of collecting ransoms in the name of the poor which no peasant ever saw and feeding his troops off crops they needed to pay taxes and tithes. Luther, while corresponding with Hutten and appreciative of the knights’ support, had already made clear to other correspondents that he was distancing himself from them as he did not want his movement involved in a military action that not only challenged secular authority but was not condoned by scripture.

Sickingen kept Trier under siege for a week before he ran out of gunpowder and, at the same time, received word that Elector Louis V, Count Palatine and Philip I of Hesse were coming to the aid of Greiffenklau and that the Imperial Council had condemned him for the attack. He withdrew to Ebernburg and then to Nanstein Castle in Landstuhl where he was confident his defenses would hold until Hutten could return from Switzerland with reinforcements, or his fellow knights could arrive.

When the armies of Greiffenklau, Louis V, and Philip I arrived at Nanstein in May 1523, however, they came armed with cannon which destroyed the castle’s defenses in a week of bombardment. Sickingen was mortally wounded, surrendered on 7 May, and died. Hutten, meanwhile, had met with Zwingli who had no more interest in supporting an armed uprising than Luther, and died of syphilis in Switzerland having failed to rally any support from anyone.

Conclusion

The lesser nobles who had joined Sickingen’s Brotherly Convention of Knights were punished through the confiscation of their lands and family castles and were dominated by the higher nobility. To pay the various fees demanded, the lesser nobles raised taxes on the peasants who were already struggling, and, by the fall of 1524, tensions erupted in the German Peasants’ War which, by the time it concluded in 1525, had claimed at least 100,000 lives among the peasantry alone.

Luther had further distanced himself from Sickingen after Trier as he relied on the support of nobles like Philip I and Frederick III and, in 1525, called for the execution of any rebellious peasants, essentially placing Sickingen and Hutten in the same camp with the peasantry as rebels he had had nothing to do with even though both the peasants and the knights had been inspired by Luther’s movement. Sickingen and Hutten had been ardent supporters of his cause, the first nobles to openly advocate for him, as they had seen his efforts as coinciding with their own interests in social reform. Asch comments;

A strong anticlericalism and commitment to an overall reform of both church and empire importantly shaped Sickingen’s and Hutten’s allegiance in the debate about Luther. Yet both died before the impact of the Reformation became fully visible and their strong and outspoken support for Luther remained exceptional among members of the nobility during the early stages of the Reformation. (Rublack, 566)

Sickingen and Hutten believed that a German Church, founded on Luther’s vision, would encourage national unity but the Reformation in Germany splintered fairly quickly into sectarian divisions. Notable early supporters of Luther such as Andreas Karlstadt (l. 1486-1541) and Thomas Muntzer (l. c. 1489-1525) broke with Luther to establish their own reform movements. Muntzer even led peasant troops during the war, allying himself with the knight Florian Geyer (l. c. 1490-1525) and others who had also initially supported Luther’s cause. Even if the Knight’s Revolt had succeeded in taking Trier, therefore, it is unlikely Sickingen and Hutten would ever have been able to realize their goal of religious and social unity.