Knossos (pronounced Kuh-nuh-SOS) is the ancient Minoan palace and surrounding city on the island of Crete, sung of by Homer in his Odyssey: “Among their cities is the great city of Cnosus, where Minos reigned when nine years old, he that held converse with great Zeus.” King Minos, famous for his wisdom and, later, one of the three judges of the dead in the underworld, would give his name to the people of Knossos and, by extension, the ancient civilization of Crete: Minoan. The settlement was established well before 2000 BCE and was destroyed, most likely by fire (though some claim a tsunami) c. 1700 BCE. Knossos has been identified with Plato's mythical Atlantis from his dialogues of the Timaeus and Critias and is also known in myth most famously through the story of Theseus and the Minotaur. It should be noted that King Minos' character in the story, as the king who demands human sacrifice from Athens, is at odds with other accounts of him as a king of wisdom and justice who, further, built the first navy and rid the Aegean sea of pirates.

The Myths

According to the myths surrounding the early city, King Minos hired the Athenian architect, mathematician, and inventor Daedelus to design his palace and so cleverly was it constructed that no one who entered could find their way back out without a guide. In other versions of this same story it was not the palace itself which was designed in this way but the labyrinth within the palace which was built to house the half-man/half-bull the Minotaur. In order to keep Daedelus from telling the secrets of the palace, Minos locked him and his son Icarus in a high tower at Knossos and kept them prisoner. Daedelus fashioned wings made of wax and bird's feathers for himself and his son, however, and escaped their prison but Icarus, flying too close to the sun, melted his wings and fell to his death. The Minotaur, the monster-child of Minos' wife, thrived on human sacrifice and Minos demanded the tribute of the noblest youth of Athens to keep the beast fed. Theseus of Athens, with the help of Minos' daughter Ariadne, killed the Minotaur, freed the young people, and returned triumphant to his home city. Both stories cast King Minos in a very unflattering light while emphasing Athenian heroes which is unsurprising as they are considered Athenian in origin.

The First & Second Palaces

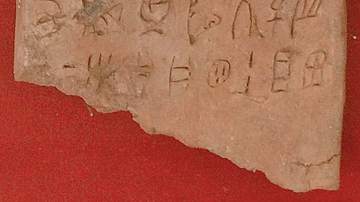

Under Minos' rule, Knossos flourished through maritime trade as well as overland commerce with the other great cities of Crete, Kato Sakro (Phaestos) and Mallia. Knossos was destroyed and re-built at least twice. The first palace identified in modern times was built c. 1900 BCE on the ruins of a much older settlement. Based upon excavations done at the site, the first palace seems to have been massive in size with very thick walls. Ancient pottery found throughout Crete, at various sites, indicate that the island was not unified under a central culture at this time and so the walls of the palace were most likely constructed to their size and thickness for defensive purposes. As the writing of this period, so-called `Cretan Hieroglyphs', has not been deciphered, nothing is known about this time save what can be discerned through archaeological evidence.

This first palace was destroyed c. 1700 BCE and re-built on a grander, though less massive, scale. Great attention was paid to intricacy of architecture and design with less effort spent on defensive walls. As the pottery of this period shows a unity of culture throughout Crete, it has been determined that the culture of Knossos prevailed at this time and the island was a unified nation under a central government. This palace had four entrances, one from each direction, all leading to the central court. As the corridors within were dark and circuitous, it is thought that this gave rise to the story of the labyrinth of Minos. The throne room was particularly impressive. According to The British School at Athens, “Two double doors led into the Throne Room with gypsum benches on three sides and the magnificent throne in the centre of the north wall flanked by the reconstructed Griffin fresco." The scholars of the British School have also speculated that the throne room was not intended for the ruler but, rather, as the seat for the goddess who would receive supplicants and sacrifices there. This theory is based upon wall paintings and other evidence found at the site which suggest the king's throne was most likely in the central court and the throne room was more ceremonial and religious in nature. The Snake Goddess of the Minoans was the supreme deity who may have been an early version of the Greek goddess Eurynome who danced with the serpent Ophion across the chaos of the primordial sea in the act of creation. Images and figures of the Snake Goddess (now at the Iraklion Museum) have been found at Knossos and elsewhere in Crete dating from this period. Further evidence of the goddess is the repetition of the motif of the double axe, most notably in the Hall of the Double Axes in the palace. There is no doubt that the double axe symbolized an important goddess of the Minoans but it is not clear whether it was the Snake Goddess or another.

The End of Knossos & Later Discovery

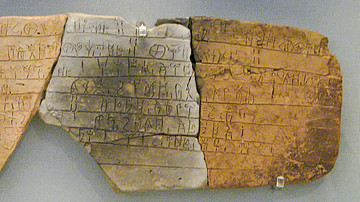

The city of Knossos, and almost every other community centre on Crete, was destroyed by a combination of earthquake and the invading Mycenaeans c. 1450 BCE with only the palace spared. The eruption of the volcano on the nearby island of Thera (Santorini) in c.1600 or 1500 BCE has long been held a major factor in the destruction of the city and second palace. Recent scholarship, however, argues against this theory citing Mycenaean activity at the palace after 1450 BCE. The Mycenaen writing system, known as `Linear B', continues in Crete after the eruption of the Thera volcano and there is further evidence that the Mycenaens re-built the damaged palace. In fact, it appears that Knossos became an important base of operations and capital of the Mycenaeans until it was destroyed by fire and finally abandoned c. 1375 BCE. The date which traditionally marks the final end of the Minoan civilization is 1200 BCE after which there is no evidence for the culture. Some scholars cite the final date as 1450 BCE with the Mycenaean invasion and others claim c.1375 or c.1300 BCE on account of the fire which destroyed both palace and city. However long the Minoans may have continued on the island, following the fire the ruins of the great metropolis were abandoned and left to decay.

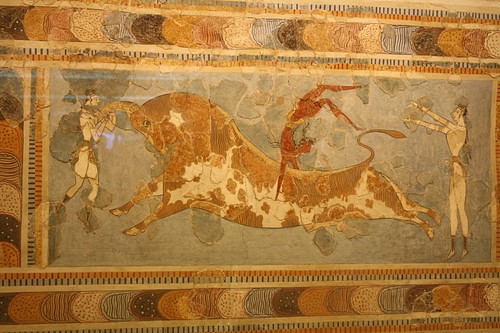

For centuries, Knossos was considered only a city of myth and legend until, in 1900 CE, it was uncovered by the English archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans and excavations were begun. Through frescoes on the walls, the excavated site revealed more about the Minoan sport of bull jumping and the ancient story of Theseus and the Minotaur (half-man-half-bull) seemed more probable than fanciful. The possibility that there existed a Minotaur became more acceptable once it was understood that, in the Minoan sport of bull-jumping, the male athlete became one with the bull as he vaulted over the bull's horns. This sport, then, it is now supposed, gave rise in ancient consciousness to the 'myth' of the Minotaur through the impression that these athletes were half men and half bulls. The story of the labyrinth also was given more credence once the intricate interior of the palace was uncovered. It was Evans who first called the ancient inhabitants of Crete 'Minoan' after King Minos of Knossos, and his efforts in excavation and re-construction, however controversial, paved the way for all future work in both physical and cultural anthropology concerning the Minoan civilization.