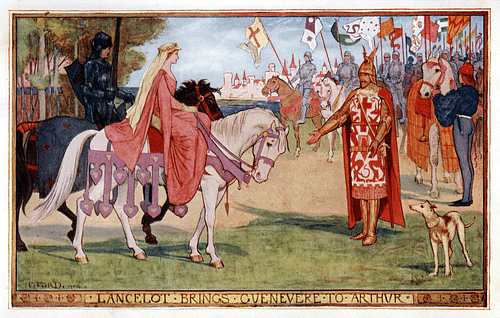

Lancelot, also known as Sir Lancelot and Lancelot du Lac (“Lancelot of the Lake”) is the greatest knight of King Arthur's court and lover of Arthur's wife, Queen Guinevere, best known from Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte D'Arthur (1469 CE). The character was first developed by the French poet Chretien de Troyes (l. c. 1130-1190 CE) in his Lancelot or the Knight of the Cart (c. 1177 CE) who introduced Lancelot's affair with Guinevere as well as his reputation as a famously skilled warrior.

The character may have originated in Ireland from the fertility god Lug (or Lugh), as perhaps is the case with another of Arthur's knights, Sir Gawain. Gawain's character was established as the greatest knight by Geoffrey of Monmouth in his History of the Kings of Britain (1136 CE) before Chretien elevated Lancelot's role and developed his character. Afterwards, many of Gawain's central attributes (especially his martial skills) were given to Lancelot by later poets following Chretien's model.

In Malory's work, Lancelot's affair with Guinevere finally destroys the unity of Arthur's Round Table of noble knights and allows the villain Mordred to usurp the throne. Mordred's actions lead to the destruction of the kingdom and the deaths of most of the greatest knights while Arthur, mortally wounded, is taken away to the mystical isle of Avalon. The Lancelot-Guinevere love affair is among the most famous in world literature and defines the lovers even as they struggle to resist their passion, rendering them finally heroic figures brought down by the fatal flaw of their relationship.

Origin Theories

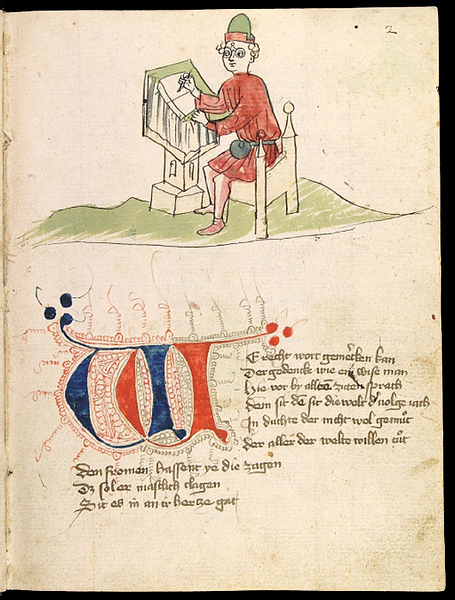

Among scholars, it is generally agreed that the character of Lancelot originated in the work of Chretien de Troyes who first introduced him in his poem Erec and Enide (c. 1170 CE) and used him again in his Cliges (c. 1170's CE) but did not develop the character until his Lancelot or the Knight of the Cart.

Some scholars, however, claim that Lancelot originated in Ireland as a fertility god and was transformed by poets and bards, embellishing on mythological themes, into a noble knight. Scholars Roger Sherman Loomis, Maria Leach, and Jerome Fried claim that Lancelot was originally an Irish solar figure. Leach and Fried note:

The great Irish sun god Lug bore the epithet Lamfada, “Long Hand.” Lug was taken over by the Welsh as Lluch Llauynnauc, Lluch “White Hand.” Lluch, in the Black Book of Carmarthen and Kilwch, has become a warrior of Arthur's, just as the Irish sea god Manannan, in the same texts, is enrolled in Arthur's train as Manawyddan, son of Llyr. Lug turned up in French romance as (at least) two personages. His name was corrupted into Loth; his sobriquet, under the influence of the French name Lancelin, became Lancelot. The accident that lluch as a common noun meant “lake” led to the conversion of the name Lluch into the title “du Lac”, and to Lancelot's acquiring a foster mother, the Lady of the Lake. (602)

Leach and Fried build on the earlier work of Loomis, one of the most highly regarded Arthurian scholars of the 20th century CE, but scholars in the present day largely dismiss this claim as needlessly complicated. Arthurian scholar Norris J. Lacy, for example, claims the simplest explanation for the character's origin is Chretien and the wealth of European legend and medieval folklore he was able to draw from.

Scholar Denis de Rougemont agrees that Chretien is Lancelot's creator but argues that Chretien's work, like all the literary works of courtly love, is actually religious allegory related to the heretical sect of the Cathars and Lancelot would represent the Cathar adherent struggling against the temptations of the body as he tries to protect and serve the goddess Sophia (wisdom) personified in the character of Guinevere. This claim has been repeatedly challenged but never fully refuted.

Development in Chretien

Chretien was closely associated with the region of Southern France in which Catharism flourished and, more importantly, was patronized by Marie de Champagne (l. c. 1145-1198 CE), daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine (l.c. 1122-1204 CE), both of whom were suspected by the Church of supporting the heretic Cathars. It is possible Denis de Rougemont's theory is correct as Eleanor and Marie do not seem to have had much use for the Church, both patronized poets and artists who were most likely involved in the heresy, and a son-in-law of Eleanor's was a Cathar bishop. Further, Chretien claims that the subject matter of his Lancelot was given to him by Marie de Champagne who asked him to form it as poetry.

Whether the works were religious allegory or simply entertainment, the knight Lancelot makes his first appearance in Erec and Enide as little more than a name on a list of the noble knights of Arthur's court and then plays a more substantial role in Cliges as one of the knights the hero must conquer. In his Lancelot, however, Chretien fully develops the hero as the main character and also introduces the plot device which would define Lancelot for almost every other writer who came after: Lancelot's affair with Arthur's queen Guinevere.

The story opens with Guinevere abducted by the villain Meleagant and Arthur sending his knights in pursuit. Lancelot outdistances the others but rides his horse so hard and so fast that it dies and he must continue on foot. He meets a dwarf driving a cart who says he knows where Meleagant has taken Guinevere and will help Lancelot if he consents to ride in the cart. Since carts were associated with criminals, Lancelot hesitates for a moment - fearing he will be dishonored - but then mounts the cart. For the rest of the journey, he is mocked and humiliated for riding in a cart instead of on a war horse like a proper knight. When he finally reaches Guinevere and tries to free her, she rebukes him for his earlier hesitation as he placed his own honor above his devotion to her.

To win her back, Lancelot has to agree to lose at a tournament against unworthy opponents until Guinevere tells him to win instead. In the end, Lancelot kills Meleagant and frees Guinevere who thanks him politely in public although the two have been carrying on an affair privately. The love triangle of Arthur-Guinevere-Lancelot was most likely borrowed from the earlier tale of Tristan and Isolde, originally an Irish story, in which the knight Tristan falls in love with Isolde, the fiancé of his uncle King Mark. Chretien used the Tristan tale in his Cliges and claims that he wrote his own version of Tristan and Isolde which was not well received. It is thought, therefore, that he may have created his Lancelot character from his failed Tristan manuscript. Whatever the inspiration for the Lancelot-Guinevere affair, it would become central to the Arthurian Legends.

Standard Tale & Ulrich's Deviation

In his introduction to the work From Camelot to Joyous Guard, Norris J. Lacy writes:

It is a peculiar characteristic of Arthurian literature that much of it, whether in the poems of Chretien de Troyes or in later romances, is not really about Arthur. The king and the Arthurian court provide a focal point for the narration and a standard of conduct for the knights, but it is someone else's story. (xviii)

That story is the tale of Arthur's knights and their adventures but the underlying drama, slowly unfolding in Arthurian works after Chretien, is the Lancelot-Guinevere affair with the notable exception of the German work Lanzelet (c. 1194-1204 CE) by the poet Ulrich von Zatzikhoven. Ulrich provides Lancelot with a backstory and omits any reference to an affair with Guinevere. In the Lanzelet, the main character is a highly moral hero on a journey of self-discovery.

Ulrich's poem opens with a young prince Lancelot, son of King Ban, abducted by a mermaid and carried off to an island of women where he is raised with no knowledge of his past or noble birth. He is trained in all aspects of culture as well as martial arts. At the age of 15, he feels he must prove himself and goes off on adventures during which he learns his identity and that he is King Arthur's nephew. He goes to Arthur's court to become a knight, endures various trials in combat and takes part in the rescue of Guinevere, who has been abducted by the untrustworthy Valerin, along with the other knights. In the end, he becomes lord of his wife Iblis' realm and the two live a charmed and happy life.

The concept of Lancelot as the best knight or most perfect knight is taken from Ulrich and developed in the Vulgate Cycle (also known as the Lancelot-Grail Cycle, Prose Lancelot, Pseudo-Map Cycle, (1215-1235 CE) which revives the Lancelot-Guinevere affair. In this work, Lancelot is carried off by the Lady of the Lake after the death of his father, King Ban. She raises him in secret along with his cousins Lionel and Bohort until he is 18 when she brings him to Arthur's court to be knighted as Sir Lancelot du Lac. Lancelot instantly falls in love with Guinevere but says nothing of his love for her until he finally unburdens himself to his close friend, Galeholt, Lord of the Distant Isles, who encourages him to tell Guinevere. When he does, he finds that she has also fallen in love with him and they begin their affair.

Prior to the affair, Lancelot is consistently referred to as the best of all knights and his adventures are always stunning successes. He liberates the castle of Dolorous Guard, renaming it Joyous Guard, and performs many other great feats but his love for Guinevere becomes his central preoccupation. At one point, the Grail King Pelles seizes on Lancelot's infatuation to trick him into sleeping with Pelles' daughter Elaine. Pelles enchants Lancelot with a potion which makes him believe Elaine is Guinevere; otherwise he never would have gone with her since he was completely devoted to Guinevere.

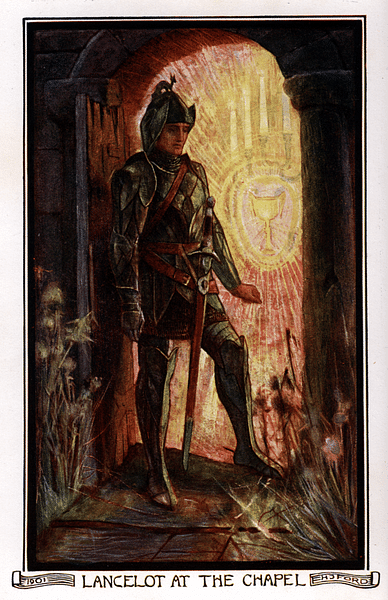

When Guinevere finds out about his tryst with Elaine, she rejects him and he goes insane with grief, wandering aimlessly until he is found by Elaine and his sanity is restored. He then returns to Camelot in the company of knights Guinevere has sent to look for him. Although Guinevere sees his relations with Elaine as a betrayal, his night with Elaine was destined because she would give birth to their son Galahad, the perfect knight, who grew up to complete what Lancelot, owing to his sin with Guinevere, could not do: find the Holy Grail.

Arthur's knights continue to perform great deeds until Lancelot's affair with Guinevere comes to light and fractures the court. In the end, most of the knights are killed in battle fighting against the usurper Mordred and Arthur's grand vision of the Round Table and a kingdom founded on justice is destroyed. The Vulgate Cycle develops numerous threads from earlier versions of the legends, some now lost, and weaves together a sprawling narrative of interconnected plotlines and characters to produce the first recognizable version of the Arthurian Legend as it stands today. This work was then edited and revised as the so-called Post-Vulgate Cycle (c. 1240-1250 CE), which is the text Malory worked from.

Malory's Lancelot

Sir Thomas Malory (c. 1415-1471 CE) was a political prisoner at Newgate in London in 1469 CE when he wrote his Le Morte D'Arthur. His version of the legend is informed by the period of the War of the Roses (1455-1487 CE), the conflict which landed him in prison, on and off, beginning in c. 1451 and lasting until his release from Newgate in 1470 CE. Arthur's court presides over a strong, unified kingdom until the internal conflict caused by Lancelot's affair with Guinevere breaks that unity and leads to the kingdom's destruction; mirroring Britain's situation with the War of the Roses in which the houses of York and Lancaster fought each other for control of the throne and threw Britain into almost constant conflict for over thirty years.

In Malory, Lancelot is again the best knight in the world who controls his feelings for Guinevere and serves Arthur faithfully until he can no longer keep his love a secret and confesses himself to her. She is also in love with him and yet they refuse to betray Arthur as long as possible before finally giving in to their desires. Malory develops each of his characters carefully as individuals, providing them with psychological and emotional motivations and building his narrative toward the final cataclysm of the Battle of Camlann in which Arthur defeats Mordred but most of his knights are killed and he, mortally wounded, is taken away to the Isle of Avalon. Malory's narrative is so layered and his characters so complete that his work has been called the first novel in English and the first in the western world.

After the disastrous Battle of Camlann, Guinevere blames herself for Arthur's fall and enters a nunnery. She and Lancelot see each other one last time but she refuses his goodbye kiss, and he leaves her to become a hermit. The former queen lives out the rest of her life in service to others until she falls ill. Lancelot hurries to her sick bed but she dies before he can reach her; he dies of grief six weeks after her and is buried at his castle of Joyous Guard.

Malory's Lancelot is the model of chivalry, honor, and Christian virtue, and Guinevere is the noble, beautiful, and charitable Christian queen, but their fatal flaw is their attraction to each other which neither can resist. In spite of their best efforts to do what they know is right, they cannot control their passions, and this finally destroys them and the grand court of Camelot. Even so, they try to make amends for their affair, and Malory clearly sympathizes with the lovers who fall from grace along with all the other characters in the story but who still strive to be better than they are.

Conclusion

Lancelot's failed quest for the Holy Grail illustrates this effort as he, the best knight, should be the one to find the grail but, because of his adultery with Guinevere, is prevented. He is given a vision of the grail but will never find it in the same way that he has a vision of himself, of who he should be, which he cannot realize because of his love for his best friend's wife. This does not prevent him from trying, however, and his many great feats all go to show how determined he is to truly be the best knight in the world that everyone, except himself, believes him to be. This aspect of Lancelot's character is what has made him so compelling and popular even before the publication of Le Morte D'Arthur in 1485 CE. Tales of Lancelot's adventures and his affair with Guinevere appear in poems from the Netherlands, Spain, and Italy, among others, pre-1485 CE, and he was the best-known and most admired of Arthur's knights then, just as he is in the present day.

Malory's work fell out of favor during the Renaissance and was only revived through the efforts of the British poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson in his Idylls of the King in 1859 CE. Since then, the Arthurian Legends generally and Malory's work specifically have only grown in popularity. People who have never read Le Morte D'Arthur or any of the other Arthurian works recognize the name of Lancelot as associated with the concept of the brave, chivalric knight. Readers who know the character and his story, however, recognize the deeper aspect of Lancelot's tale. Anyone who has tried to better themselves, in any area, will see in Lancelot a kindred spirit who never stops struggling to become the best version of himself.