Legio IX Hispana served with Julius Caesar in Gaul and against Pompey in the Civil Wars. Later, it fought alongside Augustus in his Cantabrian Wars and was one of the four legions Claudius took with him in his invasion of Britain in 43 CE. It survived mutiny and near decimation twice, only to recover. Although suffering heavy losses during the revolt of Boudicca, the legion rebounded and accompanied Agricola in his war against the Caledonians. The legion disappeared sometime after 120 CE.

Caesar's Ninth Legion

In the time of Caesar (100-44 BCE) and Pompey (106-48 BCE), legions of the Roman army were known by a number, not a name. A Ninth Legion served under Caesar during his time as governor of Further Spain (Hispania Ulterior) and later in both his Gallic Wars and against Pompey in the Civil Wars. It was during the legion’s time under Caesar that it initiated a mutiny, and it almost cost the Ninth its existence. At Placentia in northern Italy, the army protested their meager pay and lack of spoils of war that often supplemented a Roman legionary's meager pay.

According to Philip Freeman’s Julius Caesar, he chose to address the legions as a whole. Considered by many to be a wise but firm leader, he spoke to them as spoiled children, telling them they were proud soldiers, not a horde of ravaging barbarians. Freeman considered the incident an example of Caesar’s style of leadership. He threatened to decimate the entire Ninth as both a punishment and a warning. In a decimation, every tenth man is executed. After his speech, the legionaries made a plea to save the guilty legion, a legion that had served him proudly in the past. He agreed only if given the names of the ringleaders of the mutiny. Twelve of them were chosen by lot and then executed.

The incident forgotten, Caesar and his legions continued on against Pompey. Although some sources claim the legion was disbanded, a Ninth was raised by Octavian (the future Roman emperor Augustus, r. 27 BCE - 14 CE) from Caesar’s veterans and used in his war against Mark Antony. Later, under Augustus, the Ninth (with the title of Macedonica) participated in his Cantabrian Wars (27-19 BCE), earning the new title of Hispaniensis (stationed in Spain) which was later shortened to Hispana. After its time in Spain, it was sent to the Balkans with Aquileia as its base.

Mutiny under Tiberius

In 14 CE, the IX Hispana was stationed in Pannonia when Augustus died. Like its fellow legions of the Rhine frontier, the Legio IX was thrown into disarray and eventually into the middle of another mutiny. The Roman historian Tacitus wrote in his Annals of the incident:

This was the state of affairs at Rome when a mutiny broke out in the legions of Pannonia which could be traced to no fresh cause except the change of emperors. (Annals I. 16)

After hearing of the emperor’s death and the ascension of Tiberius (r. 14-37 CE), Junius Blaesus, the commander of the province’s three legions (VIII Augusta, IX Hispana, and XV Apollinaris) allowed his men to rest from the usual military duties for either mourning or rejoicing, but instead of promoting quiet, it led to demoralization and quarreling. One of the more outspoken of the troops, Percennius, chose to incite his fellow legionaries. While speaking of the poor pay and the hardships of soldiering, he spoke out against the new emperor: "When … will you dare to demand relief, if you do not go with your prayers or arms to a new and yet tottering throne?" (Annals, I. 27) As the legionaries cheered, addressed them and tried to calm their indignation; mutiny was not the answer. In the end, an envoy was sent to Rome to present their concerns. Unfortunately, the calm was short-lived as the mutiny broke out again, and this time it became violent.

Arguing continued, with two legions, the VIII and XV, actually drawing swords against each other, "but the soldiers of the ninth interposed their entreaties and when these were disregarded, their menaces." (Annals, I. 23) Hearing of the mutiny, Tiberius sent his son Drusus to Pannonia. Upon his arrival, the legionaries, seeing omens in the sky, began to rethink the mutiny. Seizing the opportunity, Drusus ordered the centurions to walk through the camp and speak to the legionaries. The mutiny was finally suppressed when Drusus addressed the men. He said he was not going to be conquered by either terror or threats and ordered the chief mutineers (Percennius was one) executed. A search was made throughout the camp for chief mutineers who were immediately killed by the centurions. Fearing the worse, the mutinous legions chose to break camp and return to their winter quarters.

First the eighth, then the fifteenth legions returned; the ninth cried again and again that they ought to wait for the letter from Tiberius, but soon finding themselves isolated by the departure of the rest, they forestalled their inevitable fate. (Annals, I. 30)

Legio IX Hispana in Africa

In 20 CE, the legion under Gaius Fulvius was sent from Pannonia to North Africa to help III Augusta in its campaign against Tacfarinas and his army. In the pursuit of the Numidian commander, a centurion named Decrius led a cohort (480 men) of the Ninth in a failed charge against Tacfarinas, but the inexperienced legionaries fled back to the camp and barricaded themselves inside, leaving Decrius to certain death. The governor Lucius Apronius was incensed, speaking of the dishonor and demanding the decimation of the cohort. Tacitus wrote:

He flogged to death every tenth man drawn by lot from the disgraced cohort. So beneficial was this rigor that a detachment of veterans, numbering not more than five hundred, routed those same troops of Tacfarinas on their attacking a fortress named Thala. (Annals, III. 21)

In 22 CE, the Ninth Legion, as a whole, would serve under Cornelius Scipio against Tacfarinas in a successful attack, driving them back into the desert. With the war near an end, Legio IX was sent home. Tacfarinas would attempt to rebuild his army, but his rebellion would ultimately die with him.

Britain

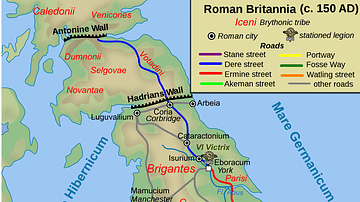

Over the next two decades, the legion would remain active. Along with II Augusta, VI Victrix, and XX Valeria Victrix, governor Aulus Plautius of Pannonia took the IX Hispana to partake in Claudius’ (r. 41-54 CE) invasion of Britain in 43 CE. The Ninth was initially stationed at Londinium but later moved to Lindum. Little is heard of the legion’s activities in Britain until 60 CE during the Boudican Revolt. Led by their commander Petilius Cerialis, four cohorts of the Ninth, on their way to provide relief at Camulodunum, were ambushed by Boudican rebels and almost wiped out. Cerialis and part of the cavalry survived. Later, 2,000 men of Legio XXI Rapax were sent to replace the Ninth’s slain legionaries.

During the Year of the Four Emperors (69 CE), cohorts of IX Hispana and other legions would march alongside the victorious Vitellius against Emperor Otho at the First Battle of Bedriacum and with him again in his defeat at the Second Battle of Bedriacum against Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE).

In 83 CE, the governor of Roman Britain, Gnaeus Agricola, took the Ninth with him into Scotland to battle the Caledonians where the legion suffered a major defeat. Agricola’s son-in-law, Tacitus (c. 56 - c. 118 CE) wrote of the defeat:

The tribes inhabiting Caledonia flew in arms, and with great preparations, made greater by the rumors which always exaggerate the unknown, themselves advanced to attack our fortresses, and thus challenging a conflict, inspired us with alarm. (Agricola, 25)

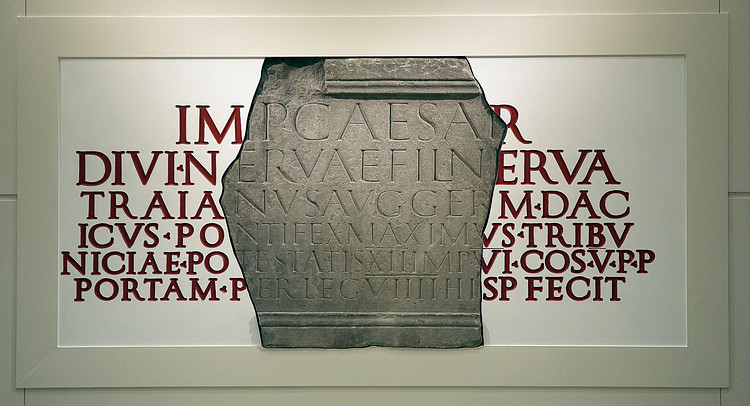

Learning that the Caledonians were going to divide their army, he split his into three divisions. Abruptly, the Caledonians changed their plans "and with their whole force attacked by night the ninth Legio, as being the weakest, and cutting down the sentries, who were asleep or panic stricken, they broke into the camp" (26). Agricola would later defeat the Caledonians at Mons Graupius. He was planning a second invasion when he was recalled by Emperor Domitian (r. 81-96 CE). After near-destruction, the legion moved from their base at Eburacum (York) to Carlisle. Although there is some evidence that the legion was with Domitian in Dacia, little is heard of it until 120 CE when it completely disappears.

The Lost Legion

There are a number of theories concerning the lost legion:

- they were wiped out by the Caledonians

- they were destroyed during the Second Jewish Revolt of 132 CE

- they were annihilated by the Parthians in 161 CE

Historians have generally accepted that the legion was wiped out by the Caledonians in Scotland in 122 CE and was stripped of their sacred eagle and standards. The Ninth was the most northern of all the British legions. Unlike other legions of Britain, the Ninth was not involved in the building of Hadrian's Wall. Some maintain that the lost legion may have initiated the construction of a wall that would keep the barbarians to the north out of Britain. One possibility is that the Caledonians lured the commander of the Ninth to a meeting to discuss peace terms. Emperor Hadrian wanted peace, not war, and had no ambition to expand the borders of the Roman Empire. Knowing this, the commander could have easily taken the legion with him to meet the Caledonians. Upon arriving, the legion would have met their doom. After the IX Hispana's disappearance, another legion was assigned to replace it in 122 CE.

To counter the idea that the legion was eliminated by the Caledonians, some note the long, distinguished careers after 120 CE of two of the legion’s tribunes: Lucius Korus and Lucius Saturninus. Others point to inscriptions found in Nijmegen in the Netherlands that show the Ninth to be out of Britain and on the Rhine after 122 CE.

Some speculate that the Ninth was destroyed in Judea during the Bar-Kochba Revolt of 132-135 CE; however, there is no evidence of the legion leaving Britain or being stationed in the East. The only two legions to be involved in a revolt in Judea were X Fretensis and VI Ferrata. The historian Cassius Dio (c. 164 - c. 229/235 CE) cites a legion being destroyed by the Parthians at Elegeia in Armenia in 161 CE, but the only legion in the region was the XXII Deiotariana, and its final days are also speculative. Some historians claim that the XXII was destroyed during an uprising in Alexandria in 122 CE. However, Historian Stephen Dando-Collins claims that it met its end at the hands of the Parthian army in Armenia during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180 CE). Therefore, this could be Dio’s legion. The Ninth had a long, troubled history. It faced decimation, survived a mutiny, and lastly, is the only legion to be called "the lost legion." No one will probably ever find out what really happened.