Parthia had always been a thorn in the side of the Roman Empire. The initial campaigns by Crassus and Mark Antony were total failures, and although Trajan and Syrian governor Cassius made some progress in the 2nd century CE, both failed to eliminate the Parthians as a viable threat. The last big clash came in 198 CE under Septimius Severus, which ultimately achieved nothing but left both empires weakened.

Failure at Carrhae

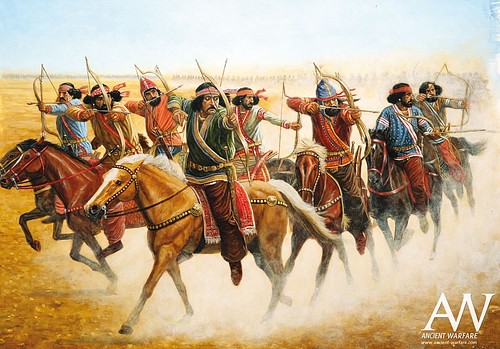

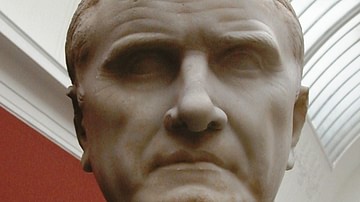

In the early days of the First Triumvirate, Roman commander Marcus Licinius Crassus (115-53 BCE), in search of glory and riches, led seven legions in an unprovoked attack on the Parthians at the Battle of Carrhae, 53 BCE. The battle proved to be an absolute disaster from the beginning. The Roman army had never encountered anything like the highly skilled Parthian cavalry who were specially trained to fight on open terrain. The battle’s result was one of the worse military disasters in Roman history. In the end, 20,000 Roman soldiers were killed, 10,000 were captured, and only about 5,000 escaped the bloodbath. The Parthians had proven to be a formable enemy. The main strength of Parthian warfare, as demonstrated at Carrhae, was the all cavalry army: heavily armored cataphracts carrying lances and lightly-armored mounted archers. They were swift-moving and rapid-firing, emphasizing mobility and expert horsemanship with quick charges and feigned retreats.

Other attempts against the Parthians would follow. A decade after Carrhae, on the eve of his assassination in 44 BCE, Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) had made plans to return to the East and battle the Parthians. In 36 BCE, five years before the Battle of Actium against Octavian, Mark Antony (83-30 BCE) led his legions into the East but withdrew amid heavy losses without success. In 66 CE, Roman emperor Nero (r. 54-68 CE) was considering a full invasion until the Great Jewish Revolt of 66 CE forced him to cancel his plans and redirect his legions. His generals were able to arrange a compromise and the planned invasion died with him.

The Campaigns of Trajan & Cassius

The next attempt was by Emperor Trajan (r. 98-117 CE). After conquering the rebellious Dacians, he turned his eyes further eastward. Some believe he only fought the Parthians for personal reward and glory instead of territorial gain. In his attack in 113 CE, Trajan took with him his two generals, Lucius Quietus and Lucius Maximus (later killed in battle), and six legions:

- Legio I Adiutrix

- Legio XV Apollinaris

- Legio II Traiana

- Legio III Cyrenaica

- Legio XII Fulminata

- Legio XVI Flavia

After taking the cities of Nisibis and Barnae, he was successful in capturing the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon where he allowed his army to loot the city. Next, he easily took the city of Seleucia. When the city of Edessa revolted against Roman occupation, it was burned. However, his plans for victory were forestalled when he repeatedly failed to take the heavily-fortified city of Hatra.

Although he had annexed both Armenia and Mesopotamia, another Jewish uprising, declining troop morale, and illness forced him to withdraw from Mesopotamia. Before leaving, he would assign Legio VI Ferrata to Caparcoma in Galilee, Legio XVI Flavia to southwest Armenia, and Legio XV Apollinaris to Satala (former base of XVI Flavia). Before he could renew his campaign, he died at Silenus in Cilicia on his return route to Rome in August of 117 CE. His nephew and governor of Upper Pannonia, Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE), was acclaimed emperor by the Roman Senate. With no intention of pursuing a Parthian campaign, the new emperor turned his back on Parthia and returned to Rome. In the decades that followed, the Parthians would rebuild, waiting for the opportunity to strike again.

In reaction to the Parthian invasion of Armenia, the expulsion of Roman magistrates, and the annihilation of Legio XXII Deiotariana in 161 CE, Emperor Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180 CE) dispatched his brother and co-emperor Lucius Verus (r. 161-169 CE) to the East. Syrian governor Gaius Avidius Cassius was appointed by the co-emperor to lead the offensive against Parthia: Rome's ablest competitor. Although not all of the legions participated, the Romans had at least eleven legions available: among them were III Gallica, IV Scythica, III Cyrenaica, X Fretensis, XII Fulminata, and the XV Apollinaris. Emperor Verus, who remained in Antioch, brought with him I Minervia, II Adiutrix, and V Macedonica. Along with the Roman commander Publius Martius Verus, Cassius and his legions first took Ctesiphon, where they burned King Vologases III’s palace, and then sacked and razed the city of Seleucia, but famine and disease forced the Romans to withdraw and return to Syria.

Unfortunately for Cassius, activities along the Danube called for an immediate return of his legions. Although he received criticism over his lack of personal involvement in the war, Emperor Verus praised Cassius’ campaign against the Parthians; Armenia had been reclaimed and the region stabilized, although at the cost of thousands of lives. While the region remained temporarily peaceful, the Parthians would soon attract the attention of a new emperor, Septimius Severus (r. 193-211 CE).

The Year of Five Emperors

With the murder of Emperor Commodus (r. 180-192 CE) in December of 192 CE, the imperial throne was claimed by five different individuals. 193 CE became known as the Year of Five Emperors. The former governor and senator Publius Pertinax - who had fought with Cassius in Parthia - was acknowledged as emperor by the Senate, but he soon ran afoul of the Praetorian Guard when he tried to restore discipline. He was murdered by 200 of the Guard after only three months on the throne. The next claimant was Marcus Didius Julianus who had the support of the Praetorian Guard, but he, too, would be murdered in his bath after only two months by the same Guard who had supported him.

The Guard had grown concerned about the mindset of the approaching Severus and his legions as Severus had been a supporter of Pertinax. Proclaimed as emperor by the Senate, he marched to Rome accompanied by the legions X Gemina, XIV Gemina Martia Victrix, I Adiutrix, and II Adiutrix. Upon reaching the city, Severus showed little mercy and abolished the Praetorian Guard for their murder of Pertinax, executing all who participated in the former emperor’s murder and banishing the rest. A newly formed Guard, double its previous size, contained men from his own legions.

With his position in Rome secure, his next concern was Percennius Niger, governor of Syria, who had ten legions and laid claim to the throne. In 195 CE, Severus crossed over to Asia Minor from Thrace to confront Niger and his legions. First, he laid siege to the city of Byzantium forcing Niger to abandon the city. Severus’ army led by Tiberius Claudius Candidus followed the would-be claimant and defeated him at the Battle of Nicaea, but Niger escaped. The two armies clashed again at Issus where Niger again escaped, fleeing to Antioch with the intent of finding refuge in Parthia. He was finally captured and beheaded. His family, held hostage in Rome, was also murdered. Due to the city’s support of Niger, Severus’ legions returned and laid siege to Byzantium until, on the brink of starvation, it finally surrendered. While his legions fought Niger, the emperor was embroiled with rebels from the kingdoms of Osroene and Adiabene. With a base at Nisibis, Severus’ army swept across both kingdoms. With their surrender, Severus returned home.

Having defeated Niger, the emperor focused his attention on a final claimant: Clodius Albinus, governor of Britain. Although the governor had initially supported Severus, Albinus learned that Caracalla (Severus’ young son) was the emperor’s chosen successor and not him. Embittered, he crossed into Gaul with his three legions: II Augusta, VI Victrix, and XX Valeria Victrix. With his eastern legions behind him, Emperor Severus met Albinus in 197 CE at the Battle of Lugdunum where the would-be usurper was killed.

Severus' Parthian Campaign

By 197 CE Septimius Severus had secured his place on the Roman throne. However, while he was battling Albinus, the Parthians took advantage of his absence and laid siege to Nisibis. Enraged, Severus was determined to eliminate the Parthians as a threat to Rome. With the support of his legions, he turned his attention eastward to Parthia. Due to the heavy losses at Lugdunum, Severus formed three new legions: I Parthica, II Parthica, and III Parthica - all three were recruited from Macedonia and Thrace and used the centaur as their emblem. There were now 33 legions in the Roman army - almost 500,000 men.

In the spring of 198 CE Severus led his three new legions, several European legions, and the Praetorian Guard into Asia Minor to do battle against the Parthians. The Parthian king Vologases quickly withdrew from Nisibis when he heard of the approaching Romans. However, before facing Vologases, Severus fought a brief battle against the kingdom of Osroene, an ally of the Parthians, forcing their surrender. From there, Severus approached the city of Seleucia where he discovered it had been abandoned. Likewise, the city of Babylon was also found abandoned.

At Ctesiphon, his army, like that of Trajan, was allowed to loot the city. The male population was killed while the women and children (an estimated 100,000) were enslaved. Due to the lack of provisions, Severus withdrew to winter at Nisibis. In the spring of 199 CE, Severus and his army laid siege to Hatra. With sufficient provisions and new Roman artillery, Severus was determined to take the city. Unfortunately for the emperor, many within the army grew critical of his leadership. Hatra was well-equipped with massive catapults that fired two long-range arrows at once. As the siege progressed, several of the Roman war engines were burned by containers of bituminous naphtha, killing the men inside. After a second breach in the city’s wall was made, Severus chose to wait 24 hours before entering the city, hoping for its surrender. Disgusted with Severus’ decision, many of the men refused to obey the emperor. The legions III Gallica, IV Scythica, VI Ferrata, and X Fretensis were ordered to lead an assault but were destroyed.

Having failed to take the city and with little support from the legions, Severus left Mesopotamia and travelled to Egypt, leaving I Parthica to garrison Singara and III Parthica at Rhesana. Legio III Parthica would eventually fall to the Persian Sassanian Empire under Shapur II (309-379 CE). Severus’ campaign in Parthia had achieved nothing. Legio II Parthica returned to Rome with him in 202 CE and became the first legion assigned to Italy, based outside Rome. The legion returned to the East under Septimius' son Caracalla (r. 211-217 CE) and participated in the Battle of Nisibis in 217 CE. Caracalla's attempts to died with his assassination, but the Parthian Empire was left severely weakened. In 224 CE, the last Parthian king was overthrown by Ardashir, founder of the Sassanian Empire. In Rome, the Severan Dynasty ended in 235 CE, and with the rise of Maximinus Thrax, the first of the so-called 'barracks emperors', the Roman Empire descended into the Crisis of the Third Century.