The Magi are the visitors who came to Bethlehem to worship the newly-born Jesus of Nazareth in the gospel of Matthew (2:1-2). 'Magi' is a transliteration of the Greek magos from old Persian magus ("powerful") as a reference to the Zoroastrian priests of the later Persian Empire. They were also known as famous astrologers who attempted to understand the relationship of the powers in the universe to humans.

In the King James Bible, the gospel of Matthew denoted them "wise men from the east to Jerusalem" (Matthew 2:1). In this sense, many considered that they had more knowledge about nature and the phenomena of nature. Thus, the English word 'magic' was derived from the idea that nature could be manipulated through this knowledge, for good or ill.

Herodotus claimed that the magos were originally the aristocrats of the Median nation, who were also gifted with the interpretation of dreams. With the spread of Hellenism, magos became an adjective; magas techne, or ars magica in Latin, referred to the expertise of astrology and magical rituals. All these conceptual elements come together in Matthew's story.

Matthew's Nativity

The gospels utilized the books of the Prophets of Israel concerning the final days when the God of Israel would establish his kingdom on earth, which included the raising up of a messiah ("anointed one"). The ministry of Jesus of Nazareth was framed within that tradition; the gospels consistently utilize passages from the Prophets. When Joseph discovered that Mary was pregnant before their marriage, an angel appeared to explain:

All this took place to fulfill what the Lord had said through the prophet: "The virgin will conceive and give birth to a son, and they will call him Immanuel" (which means "God with us"). (Matthew 1:22-23).

Matthew quoted Isaiah 7:14, but it has a notable historical problem. When the Hebrew Scriptures were translated into Greek c. 200 BCE (known as the Septuagint) there were some translation glitches. The above quote from Isaiah 7:14 reads almah in Hebrew, which means a young woman who has passed puberty. This became parthenos ("virgin") in the Greek translation.

The Visit of the Magi

After Jesus was born in Bethlehem in Judea, during the time of King Herod, Magi a from the east came to Jerusalem and asked, "Where is the one who has been born king of the Jews? We saw his star when it rose and have come to worship him." When King Herod heard this he was disturbed, and all Jerusalem with him. When he had called together all the people's chief priests and teachers of the law, he asked them where the Messiah was to be born. "In Bethlehem in Judea," they replied, "for this is what the prophet has written: 'But you, Bethlehem, in the land of Judah, are by no means least among the rulers of Judah; for out of you will come a ruler who will shepherd my people Israel.'" (Matthew 2:1-6)

Herod the Great (c. 75-4 BCE) sent them to Bethlehem but told them to let him know if they found the child so that he could worship him as well.

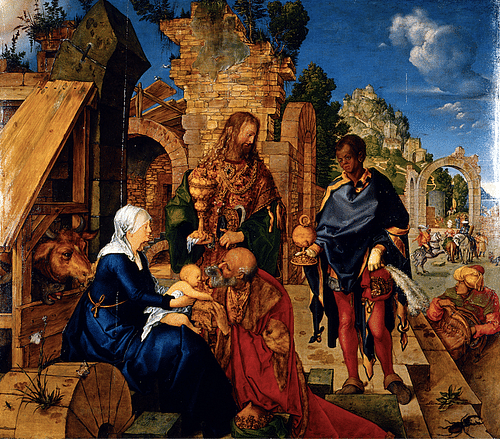

On coming to the house, they saw the child with his mother Mary, and they bowed down and worshiped him. Then they opened their treasures and presented him with gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. And having been warned in a dream not to go back to Herod, they returned to their country by another route. (Matthew 2:11-12)

The star is most likely a reference to a line from the Book of Numbers:

A star will come out of Jacob; a scepter will rise out of Israel. He will crush the foreheads of Moab, the skulls of all the people of Sheth. (Numbers 24:17)

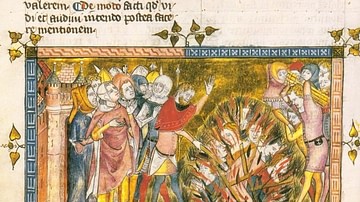

A dominant theme in Matthew's gospel was that Jesus was a prophet like Moses, who would arise in the final days (predicted by Moses in his farewell speech). Everything in this story was to remind the reader to think of the time of Moses in Egypt. That Joseph received all his information in dreams recalls Joseph in Exodus who was a dream-interpreter. The Magi visiting Herod first are used as the impetus for Herod's later slaughter of the innocents (two-year-old boys in Bethlehem) imitating the order of Pharaoh to kill Hebrew boys.

The Magi as Gentiles

Matthew's nativity story incorporates many elements that were important in the formation of early Christianity. The Magi are important characters for Matthew, as they are Gentiles (non-Jews), outsiders. Within one generation, non-Jews outnumbered the Jews in the first Christian communities. Matthew claimed that this was the intention of God from the beginning.

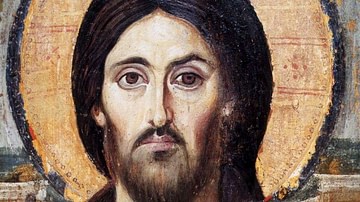

In this context, the earlier quote from Isaiah, that the child will be called Immanuel ("God with us") was a term shared by the dominant culture to describe a manifestation of a god on earth. In many of the ancient cultures, the king was often considered either divine or the product of a god and human, and thus worthy of worship. Matthew stressed the idea that it was the Magi, Gentiles, who first acknowledged a manifestation (the presence) of the God of Israel in this child.

Another Greek term, epiphaneia ("appearance" or "manifestation") contributed to the English word 'epiphany,' a revelation. Thus, the story of the Magi was incorporated into the Christian liturgy as the Epiphany, traditionally assigned to twelve days after Christmas in the Western calendar, and two weeks later in the Orthodox calendar.

The Gits of the Magi

Gold, frankincense, and myrrh were very expensive items only offered to kings or used in royal rituals. Myrrh was an herb mixed with oil and applied in the funeral preparation of the king. By the 2nd century CE, the Magi were designated as kings, most likely from the Scriptures, such as Isaiah 60:3-6: "Nations will come to your light, and kings to the brightness of your dawn. .... bearing gold and frankincense." Later Christian commentaries interpreted the three gifts as proleptic symbols for Jesus: gold because he was a king; frankincense because Jesus was worthy of worship; myrrh for his eventual death and burial.

The Origin & Names of the Magi

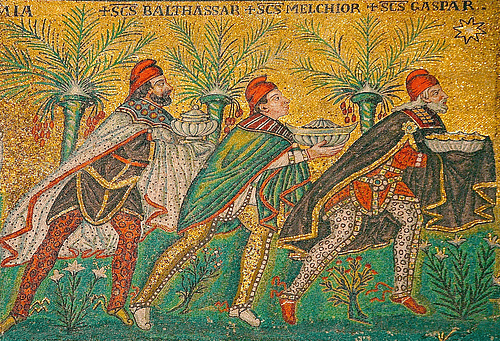

Matthew did not mention three magi, but it was derived from the three gifts. Speculation for the East includes Arabia, the trading source of frankincense and myrrh. The most common understanding remained Persia. Medieval Christian iconography portrayed them dressed as Persians, in turbans and flowing robes. They remain depicted this way in the traditional nativity scenes at Christmas.

The individual names of the Magi most likely came from a manuscript written in Alexandria, Egypt c. 500 CE. Other details were added from an 8th-century Irish manuscript. In the Western tradition they are:

- Melchior – an old man with white hair and a long beard – a king of Persia

- Gaspar – beardless and ruddy-complexioned – a king of India

- Balthasar – black-skinned and heavily bearded – a king of Arabia or a Moor

The mention of skin color may represent the nations depicted in the genealogies of Noah's sons, Shem, Ham, and Japtheth. By tradition, they all live to be over 100. Their experience led them to convert to Christianity, and stories emerged that they all died as martyrs (from the 17th-century Spanish Chronicon of Dexter).

Helena, Roman emperor Constantine I's mother, traveled to the Holy Land in 324 CE and discovered the sites of the nativity and Jesus' tomb in Jerusalem. The later legends claimed that she also found the bones of the Magi and brought them to Constantinople. They are now housed in the Shrine of the Three Kings at Cologne Cathedral. This was established by Fredrick I, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1155-1190). However, Marco Polo (1254-1324) claimed to have visited their tombs in Saveh, a city south of Teheran.

Historicity

Scholars continue to debate Matthew's story for its historical credibility. Astronomers point out that there was a retrogradation and stationing of the royal star, Jupiter, on 17 April 6 BCE. However, this event was not mentioned in any ancient literature.

Herod the Great became the most hated king in Jewish history. His court biographer, Nicholas of Damascus wrote a 20-volume Life of Herod, which has not survived intact, but much of it was quoted and used to reconstruct the history of this period by the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (36-100 CE). Outside of Matthew, there is no evidence that Herod slaughtered babies in Bethlehem. However, decades after the death of Herod, the story was credible because Herod was infamous for killing his own sons for plotting against him.

And finally, Luke's version of the nativity does not include the visit of the Magi, nor is it mentioned anywhere else in the New Testament. Nevertheless, traditional Christmas displays incorporate both versions, combing all the elements together in Bethlehem.