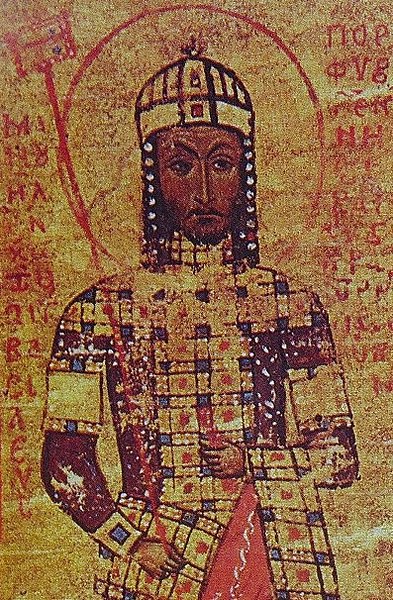

Manuel I Komnenos was emperor of the Byzantine Empire from 1143 to 1180 CE. Manuel continued the ambitious campaigns of his grandfather Alexios I and father John II to aggressively expand the boundaries of his empire. Manuel turned out to be more ambitious than his armies could support and, despite useful treaties and marriage alliances, he ultimately came unstuck with a failed invasion of Italy and then a serious defeat at the hands of the Seljuks in Asia Minor.

Succession

Manuel inherited the throne of the Byzantine Empire when the reign of his father John II Komnenos came to an unexpected end following the emperor's death in a freak hunting accident on 8 April 1143 CE. Manuel was actually the younger son, but two of his brothers had already died tragically of fever, and John had passed over his elder son Isaac, deeming him unsuitable to rule as he was too easily made angry. John had named Manuel as his successor a few days before he died in Cilicia and the new emperor had been at his father's side. Manuel's immediate problem was to get back to Constantinople before his brother Isaac got any ideas of simply taking the throne by force.

Fortunately, Manuel had an invaluable ally who would ensure his first few months as emperor went smoothly. This was John Axoukh, megas domestikos or supreme commander of the army during John II's reign. While Manuel dealt with the funeral arrangements of his father, Axouh dashed off to Constantinople and had Isaac arrested; the Church too was offered a generous annual payment to support the rightful heir. By the time Manuel arrived at his capital a new Patriarch (bishop) had been appointed, and a coronation ceremony was held. Isaac was later released in a typical act of clemency.

The historian J. J. Norwich gives the following character description of Byzantium's new emperor:

First, he was outstandingly handsome; secondly, there was a charm of manner, a love of pleasure and an enjoyment of life that stood out in refreshing contrast to John's [his father] high-principled austerity. Yet there was nothing shallow about him. A fine soldier and superb horseman, he was, perhaps, too headstrong to be quite the general that his father had been, but there could be no doubting his energy and courage. A skilful diplomat and a born statesman, he remained the typical Byzantine intellectual, cultivated in both the arts and the sciences. (274-5)

One less appreciative section of Byzantine society was the Church. Like many emperors before him, Manuel took a keen interest in ecclesiastical matters, but the Church hierarchy saw this as meddling and was not enamoured either by his overtures to the Popes or the invitation to visit Constantinople he extended to the Seljuk Sultan. In addition, Manuel's reputation as a ladies' man did not go unnoticed. Fortunately for the Church elders, Manuel would spend most of his reign campaigning in every single corner of his empire.

Foreign Policy

Alliances

Unlike his predecessors, Manuel seemed greatly attracted to the west. He favoured Latins in Constantinople, dispensing civil awards and military titles in their direction, and the emperor was even known to have participated in western jousting tournaments (and unseated a couple of Italian knights to boot). Manuel may also have introduced the somewhat indecent western novelty of trousers into Byzantine society. He married twice to princesses from the West - first, Bertha of Sulzbach and then, two years after her death, Maria of Antioch, daughter of the ruler of Antioch Raymond of Poitiers, in 1161 CE. Bertha was the sister-in-law of German king and western emperor Conrad III (r. 1138-1152 CE) and the marriage was arranged by Manuel's father in 1146 CE in order to reinforce the anti-Norman alliance, especially targeted against the Norman king Roger II (r. 1130-1154 CE) in Sicily.

The Second Crusade

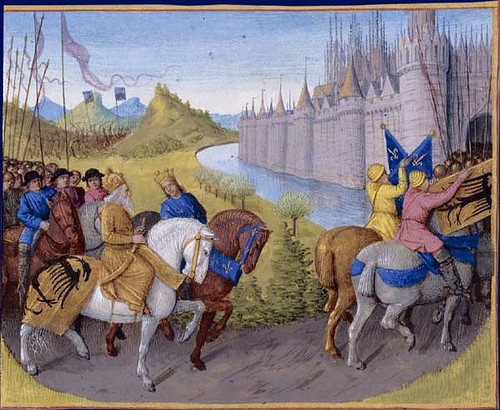

After minor victories in Cilicia, Syria, and Asia Minor in 1144-1146 CE, Manuel faced the problem of the Second Crusade of 1147-9 CE. With the goal to secure the Holy Places of Christianity from the Muslims, the Crusaders were held with suspicion by the Byzantines who thought they were really only after the choice parts of the Byzantine Empire. It was for this reason that Manuel insisted the leaders of the crusade swear allegiance to him. At the same time, the western powers considered the Byzantines rather too preoccupied with their own affairs and unhelpful in the noble opportunities they thought a crusade presented.

In more practical terms, as in the First Crusade (1095-1099 CE), the rabble of zealots and men of dubious background seeking absolution which the campaign attracted meant that as soon as the Crusader army hit Byzantine territory on its way east the pillaging, looting, and raping began. This was despite Manuel's insistence to the leaders that all food and supplies be paid for. Manuel provided a military escort to see the Crusaders on their way as quickly as possible, but fighting between the two armed groups was not infrequent. When the French contingent arrived at the Byzantine capital, things worsened still. Always suspicious of the Eastern Church and now outraged to discover Manuel had signed a truce with the Turks (seen by him as less of a threat than the Crusaders in the short term), sections of the army wanted to storm Constantinople.

The Crusaders were, eventually, persuaded to hurry on their way east with reports of a large Muslim army preparing to block their path in Asia Minor. There they ignored Manuel's advice to stick to the safety of the coast and so met disaster and defeat. The Crusade was also a blow to Manuel's carefully constructed diplomatic alliances because, involving Conrad III in person, it provided a distraction which allowed Roger the freedom to attack and pillage Kerkyra (Corfu), Euboea, Corinth, and Thebes (where silk and skilled workers were spirited off back to Palermo). Manuel's attempt to persuade Louis VII, the King of France (r. 1137-1180 CE) who was leading the Crusade, to side with him against Roger failed. In 1149 CE the embarrassment of a Serbian uprising and an attack on the area around Constantinople by George of Antioch's fleet were offset by the Byzantines recapturing Kerkyra.

Italy & Barbarossa

From 1155 to 1157 CE the Byzantines invaded Italy, helped by their ally Conrad III, although the German king was by then too ill to participate in person. The family ties between the two rulers had been strengthened by the marriage of Manuel's niece Theodora to Conrad's brother, Duke Henry of Austria. The expedition, despite the acquisition of Bari in 1155 CE, was a failure thanks to stiff resistance from Roger II's successor William I of Sicily (r. 1154-1166 CE) who could also claim the support of Louis VII. Manuel was, essentially, let down by his own fickle mercenaries and gutless local rebels. William was thus able to sign a peace settlement with the Byzantines in 1158 CE through which Manuel recognised William as king.

Things got worse for the emperor when Conrad died and he was succeeded by Frederick I Barbarossa (r. 1152-1190 CE) in 1152 CE. The long-standing alliance between the two powers was terminated, largely over the issue of Byzantine support for the Lombards and a squabble over possessions in Hungary. Indeed, the regional alliances were reversed as Manuel's 1158 CE treaty with William also identified Frederick as their common enemy.

In 1172 CE Manuel installed and supported Bela III (r. 1172-1196 CE) on the Hungarian throne and thereby gained the advantage over Frederick. Ties were strengthened further when Manuel had his daughter Maria engaged to Bela, and the Hungarian monarch was given the official title of despot and made heir to the Byzantine throne. When Manuel later had a son of his own, Alexios, the engagement was called off and Alexios was, naturally, nominated as the emperor's official heir.

Venice

Venice had provided ships to bolster the Byzantine fleet in return for trade privileges at Constantinople and within the Byzantine Empire since 1126 CE but by Manuel's reign, the Italian Republic had gained a stranglehold on eastern trade. The emperor, therefore, sought to immediately reverse the situation by confiscating Venetian goods, property and ships, and arresting 10,000 traders throughout the empire in 1171 CE. The official pretext was the accusation that the Venetians had torched the quarter of their rivals the Genoese at Galata.

Alternative Italian states such as Genoa and Pisa were supported instead but the effect on Venetian dominance was negligible and, even worse, Venice sent a fleet to exact revenge. Fortunately for Manuel, who had no fleet to respond with, the Venetians were tricked into waiting out a diplomatic parley, and in the meantime, their crews were struck down by a plague. The Doge was forced to return home where he was stabbed by a mob outraged at his incompetence. Venice would have its revenge, though, as the city led the Fourth Crusade against Constantinople in 1204 CE.

Myriokephalon

Elsewhere, campaigns went well for Manuel in Armenian Cilicia, Asia Minor, and even against Antioch, still stubbornly in Crusader's hands. On 17 September 1176 CE, though, the emperor suffered a serious defeat at the hands of the Seljuks in Asia Minor, when he was on his way to sack their capital at Iconium. At the battle of Myriokephalon (aka Myriocephalum), Manuel's army was trapped in a narrow pass in the Phrygian mountains and a full massacre was only avoided by the Sultan Kilij Arslan II generously offering a peace deal. The conditions were that the Byzantines abandon the strategic fortresses of Dorylaeum and Sublaeum. With these losses in men and defences, any further Byzantine ambitions in the region were ended and an enemy had been created who would prove more than troublesome in the coming decades. The emperor's reign was now almost over, but there was, typically, one final diplomatic coup. Manuel married off his ten-year-old son Alexios to Agnes, aged nine, daughter of Louis VII.

Death & Successor

Alexios II Komnenos (r. 1180-1183 CE) inherited the throne following his father's death of natural causes on 24 September 1180 CE, but his reign would be a brief one. In any case too young to rule in his own right, his mother Maria of Antioch acted as his regent, although she favoured her nephew and so Alexios was a mere figurehead. Maria's pro-western policies and preferential treatment to Italian merchants meant that she quickly acquired enemies at court and amongst the wider public. In 1182 CE Andronikos I Komnenos, a cousin of Manuel's, led a successful revolt, a number of Latins were butchered in Constantinople, and the regent and young emperor were ousted. Andronikos forced Alexios to condemn his mother to death, and then, in secret, the boy-emperor was strangled and his body thrown into the sea. Andronikos would only rule himself for two years, after which he was overthrown by a popular uprising.

Manuel's reign, then, had achieved little of lasting substance. He had dazzled at times but really only garnered token victories - expensive ones at that - and whenever his armies were out of sight, the regions turned their back on the emperor and looked after their own interests. The Byzantine Empire had passed its peak and was sailing through troubled waters which would culminate in the terrible storm that was the sack of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusaders in 1204 CE.