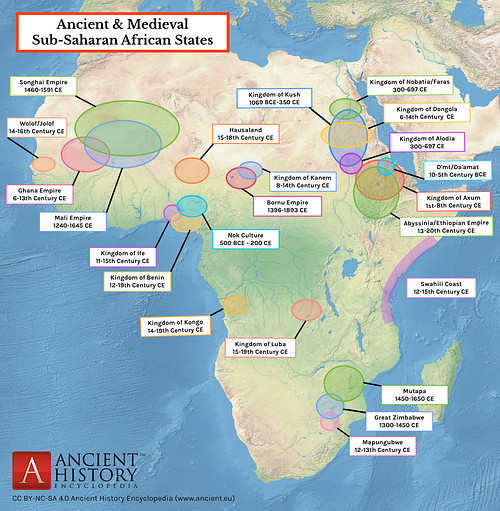

Mapungubwe, located in the very north of South Africa just below the Limpopo River, was an Iron Age settlement and kingdom which flourished between the 11th and 13th century CE. It was perhaps southern Africa's first state. Mapungubwe, whose name means either 'stone monuments' in reference to the large stone houses and walls of the site or 'hill of the jackal', prospered due to the savannah's suitability for cattle herding and its access to copper and ivory which permitted long-distance trade and brought gold and other exotic goods to the ruling elite. The site went into decline from the end of the 13th century CE, most likely due to an exhaustion of local resources, including agricultural land, and the movement of interregional trade to such sites as Great Zimbabwe further north. Mapungubwe was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2003 CE.

Mapungubwe Plateau

Without any contemporary written records, a somewhat incomplete history of the communities living in this area must be pieced together from archaeological finds only. There is also very little evidence for the existence of any state apparatus beyond the obvious wealth of the capital which would suggest a centralised authority which monopolised trade, wealth, and could command labour to build large stone structures.

The kingdom of Mapungubwe was formed by Bantu-speaking peoples who were pastoralists. The area controlled by the rulers of Mapungubwe has at its heart a large sandstone plateau, easily defended due to its inaccessibility. As with other kingdoms in the region of southern Africa, agriculture, especially cattle herding and the growing of sorghum and cowpeas, brought plenty of food and a surplus that could be traded for needed goods. Archaeology has revealed extensive layers of bones and manure, which indicate that from the 9th century CE there were large cattle herds, the traditional source of wealth and political power in southern African communities. The archaeological record for the 10th century CE shows a marked increase in the number of domesticated cattle in the area as well as cotton cultivation and weaving as indicated by abundant finds of spindle whorls.

Government & Society

The chief or king of Mapungubwe was likely the wealthiest individual in the society, that is he owned more cattle and precious materials acquired via trade than anyone else. There was also some sort of religious association between the king and rainmaking, a vital necessity for agriculture in such a dry landscape. The king and his court dwelt in a stone enclosure composed of stone walls and housing built on the highest level of the community's territory, a natural sandstone hill which is some 30 metres (98 ft) high and 100 metres (328 ft) in length. Occupation on the hill dates from the 11th century CE. That royal wives lived separately from the king is indicated by a number of separate dwellings where grindstones have been discovered. The whole complex was originally surrounded by a wooden palisade as indicated by postholes made in the rock.

The rest of the community lived in mud and thatch housing spread out below the hill, although there is one stone structure here. This area is known as Babandyanalo or K2 and, covering around 5 hectares (12.3 acres), its original settlement pre-dates the hilltop site above. Babandyanalo is abundant in cattle enclosures, burials and figurines, all attesting to the importance of this animal at the site. The total population of Mapungubwe at its peak in the mid-13th century CE was around 5,000 people.

The king was buried along with his predecessors at the top of the hill site in a demarcated area away from the dwellings while commoners were buried at the surrounding valley level. A wooden staircase connected the two levels, the sockets for the steps being clearly visible in the sandstone cliff face. There are some grander residences dotted around the outskirts of the lower level town, and these probably belonged to male relatives of the king. It is known that in Bantu society such males, serious competitors for the king's position, were not permitted to live directly within the community.

There are many other smaller but still impressive hilltop sites across the Mapungubwe plateau which are located anywhere from 15 to 100 kilometres (9 to 60 miles) from the capital. Containing stone residences and walls, they likely belonged to local chiefs who acted as vassals to the king at Mapungubwe.

Trade

The Mapungubwe plateau has a very high number of carnivore animal remains and ivory splinters, suggesting that animal hides and ivory elephant tusks were accumulated, probably for trade with coastal areas reached by the Limpopo River. The presence of glass beads, almost certainly from India, and fragments of Chinese celadon vessels indicate there was certainly trade of some sort with other states on the coast who, in turn, traded with merchants travelling from India and Arabia by sea. Contemporary with the Kingdom of Zimbabwe (12-15th century CE), located to the north on the savannah plateau on the other side of the Limpopo River, Mapungubwe would also have benefitted from locally-sourced copper and the gold trade that passed through from south-west Zimbabwe to the coastal city of Kosala. Indeed, initially, Great Zimbabwe may have been a client state of Mapungubwe. The prosperity that trade links brought would likely have led to a strengthening of political authority in order to control and even monopolise these lucrative interregional connections.

Art

Pottery was produced on a scale large enough to suggest the presence of professional potters, and it is another indicator of a prosperous society, perhaps with different class levels. Forms include spherical vessels with short necks, beakers, and hemispherical bowls while many are decorated with incisions and comb stamps. There are also ceramic disks of unknown purpose, whistles, and one giraffe figurine. In addition, cattle, sheep, and goat figurines, and small figures of highly stylised humans with elongated bodies and short limbs have been found, often in a domestic setting. The figures may have been used as votive offerings to ancestors or gods and relate to prosperity and fertility but their precise function is not known. Other finds include small jewellery items made from copper or ivory.

A particular type of decoration, only found elsewhere at Great Zimbabwe, was to beat gold into small rectangular sheets which were then decorated with geometrical patterns made by incision and used to cover wooden objects (which have not survived) using small tacks, also made of gold. One such covered object may have been a sceptre, while additional evidence of local gold-working is a rhinoceros figurine made from small hammered sheets, fragments of gold bangles, and thousands of small gold beads. These objects were found at the royal burial site, and, dating to c. 1150 CE, these are the first known indicators that gold had an intrinsic value of its own (as opposed to just a commodity currency) in southern Africa.

Decline

The kingdom of Mapungubwe was already in decline by the late 13th century CE, probably because of overpopulation putting too much stress on local resources, a situation that may have been brought to a crisis point by a series of droughts. Trade routes may also have shifted northwards and local resources run out. Certainly, the kingdoms that now prospered were to the north, such as Great Zimbabwe and then the Kingdom of Mutapa in northern Zimbabwe and southern Zambia, established c. 1450 CE.

When Europeans 'discovered' the ruins of Mapungubwe in the 19th century CE, just as with those at Great Zimbabwe, they could not believe such impressive structures were built by black Africans. Theories abounded to somehow explain their presence and confirm racist European beliefs such as attributing them to the ancient Egyptians or Phoenicians. Archaeology, however, has since proved both sites were indeed built by indigenous peoples in the medieval period. Many of the artefacts from Mapungubwe can be seen today at the University of Pretoria Museums, South Africa, while the site itself is protected as part of the Mapungubwe National Park.