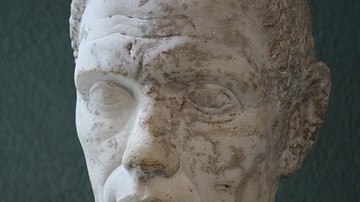

Marcus Claudius Marcellus (c. 270-208 BCE) was a five-time consul and, earning the nickname the 'Sword of Rome', he was one of the city's greatest military commanders. Active in both the First and Second Punic Wars, he also won honours for his campaigns in Gaul and the capture of Mediolanum (modern Milan). Battling Hannibal in southern Italy and then famously capturing Syracuse on Sicily, Marcellus' run of victories came to an end when he faced the Carthaginian general in 209 BCE. One year later the Roman commander was killed in an ambush near Venusia (modern Venosa), where his tomb marker still stands today. He is not to be confused with Emperor Augustus' nephew of the same name.

Early Career

Marcellus was born c. 270 BCE and first gained recognition as a military tribune during the final years of the First Punic War (264-241 BCE) against Carthage. He was made (at unknown dates) an augur, curule, quaestor, then an aedile c. 226 BCE, and finally a praetor as he climbed up the various political rankings of ancient Rome. According to the Greek-Roman writer Plutarch (c. 45 - c. 125 CE) in his biography Marcellus, he had a son, Marcus. Plutarch, in his opening paragraph, describes the character of Marcellus in the following terms:

He was, indeed, by long experience, skilful in the art of war, of a strong body, valiant of hand, and by natural inclinations addicted to war. This high temper and heat he showed conspicuously in battle; in other respects he was modest and obliging.

Northern Italy Campaigns

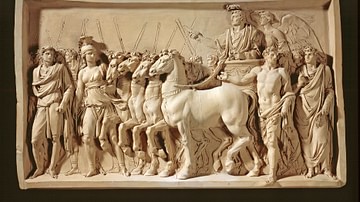

Marcellus was made consul for the first time in 222 BCE. It was a role he would take on four more times in 215, 214, 210, and 208 BCE, an unusual run made possible by the suspension of the usual election rules during the long Second Punic War (218-201 BCE). In his first consulate he established his reputation for skill and courage on the battlefield. Campaigning against the Gauls in northern Italy, he rescued Clastidium (modern Casteggio) from imminent collapse. Then, with help from Cornelius Scipio Calvus, he captured Mediolanum and famously led a cavalry charge which allowed him to kill the Insubrian chief Viridomarus in single combat. He received the great honour of the spolia opima or 'spoils of honour' for the deed - one of only a handful of such commander-duels in Roman history - and a triumph for his campaign. Marcellus' exploits were then celebrated in a popular play of the time by Naevius, Clastidium. Marcellus himself dedicated a temple to both Honos and Virtus, the Roman gods of Honour and Virtue respectively, although the project was not actually finished until 208 BCE.

Second Punic War

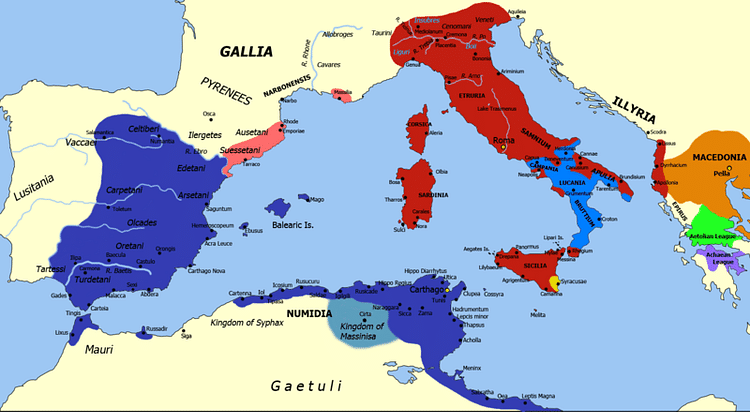

During the Second Punic War the horrors of war came much closer to home for the Romans, and commanders like Marcellus would have to face their greatest challenge. In 216 BCE Marcellus was praetor again and he was sent to defend the city of Nola in Campania from attack by the Carthaginian general Hannibal who had now invaded Italy and already won significant battles at Ticinus, Trebia, Lake Trasimene, and Cannae (218-216 BCE). Nola was held, and Marcellus was briefly given a consulship for the second time in 215 BCE before he was forced to step down, probably because his election meant neither consul was of the patrician class. Instead, he was given a proconsul command and then made consul the year after.

In 214 BCE Marcellus again defended Nola against Hannibal's forces and then recaptured from the enemy Casilinum on the Via Appia. The Roman general next switched battlefields to Sicily. After taking Leontinoi, Marcellus set his sights on the jewel of Sicily, fortress Syracuse. He blockaded the harbour with 60 artillery-mounted ships and attacked from the sea while Claudius Pulcher led an army on land to bombard the city from two sides. Still, the defenders had an ace up their sleeves in the form of the brilliant scientist and inventor Archimedes whose wicked artillery and grappling machines managed to keep the Romans at bay. After an eight-month siege, and despite Carthage sending an army of 23,000 in support, the city did finally fall in 212 BCE. The capitulation of the fortress was largely thanks to several mercenary leaders defecting to support the Romans. It was they who told Marcellus that the defenders were in the midst of a festival to honour Artemis, and the general took swift advantage by launching a night attack that took the city. In the chaotic aftermath of the city's occupation, Archimedes (and many others) were ruthlessly killed, although Marcellus had ordered that the scientist be spared.

Marcellus promptly shipped back as much fine art booty as he could lay his hands on from his new prize in an innovative and highly successful strategy to impress his fellow Romans. Marcellus would be criticised by the historian Polybius (c. 200-115 BCE) not because it was wrong to take from the conquered but because it was dangerous to adopt the luxury-loving ways which had softened them up for defeat. The range and excellence of the Greek art which found its way from Sicily to Rome did have one effect, to inspire Roman artists to greater endeavour in their own paintings and sculpture.

More victories on the island, which included dispensing with surviving Carthaginian forces at Agrigento, ensured Marcellus fully deserved his ovatio (one step down from a full Triumph) in Rome in 211 BCE. They were the first military celebrations of the Second Punic War and, with Scipio Africanus' victories in Spain in 209 BCE, the conflict was finally swinging Rome's way.

The wings of fortune might have been fluttering on the side of the Romans but they still had a lethal enemy encamped in the south of the Italian peninsula to deal with. Marcellus overturned the established Roman strategy of not trying to face Hannibal's army in direct battle. Ever since Cannae and their heavy defeat there the Romans had adopted the so-called 'Fabian policy', named after Fabius Maximus Verrucosus, the dictator of 217 BCE, who earned the nickname 'Cunctator' (Delayer). Fabius knew that Hannibal might win direct confrontations but he could be worn down by attacking his allies and blocking his supplies by sea. Marcellus, on the other hand, was now eager to meet the Carthaginian head on and settle the issue sooner rather than later. The more aggressive commander thus earned the later historian Posidonius' name for the pairing of Maximus and Marcellus as Rome's 'Shield and Sword' respectively.

Death & Legacy

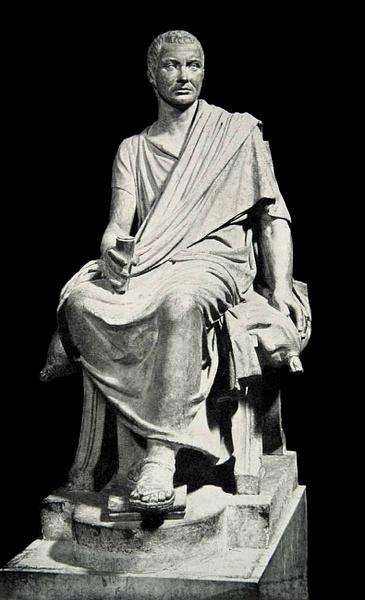

Made consul once again in 210 BCE, Marcellus was, no doubt, confident after his own victories against the Gauls and Sicilians that he could match Rome's great nemesis on a level battlefield. However, in 209 BCE, with Marcellus this time acting as a proconsul, when the pair finally met on the battlefield at Canusium the Carthaginian won. Criticised for being too passive at Canusium, fate would not give Marcellus an opportunity for revenge as he was ambushed near Venusium in southern Italy in 208 BCE. Again serving as consul and preparing to attack Locri with his colleague Quinctius Crispinus, Marcellus was killed outright while Crispinus was wounded (but died later). According to the Roman writer Livy (64/59 BCE - 17 CE), Hannibal showed the decency to give Marcellus a proper funeral but he also used the Roman's signet ring to try and deceive towns loyal to Rome with forged letters, notably Salapia. The ruse was unsuccessful because Crispinus had managed to inform them of Marcellus' death.

Meanwhile, Hannibal had the bones of Marcellus sent to Rome in a silver urn with a gold crown. Unfortunately, according to Plutarch, a contingent of Numidians intercepted the mission and cast the bones unceremoniously to the ground where they were left and lost. Livy, on the other hand, reports that the relics safely reached Rome. The speech of Marcellus' son, delivered at his father's funeral, was later published. The remains of the stone monument thought to mark the warrior's tomb still stands, rather forlornly it must be said, in modern Venosa, tucked away in an ordinary row of street houses. The great general was honoured by various statues and monuments around the Mediterranean and one, at Lindus, according to Posidonius (quoted by Plutarch) carried the following inscription:

This was, O stranger, once Rome's star divine,

Claudius Marcellus of an ancient line;

To fight her wars seven times her consul made,

Low in the dust her enemies he laid.

Marcellus's loss was a heavy blow for Rome - he had been in a position of imperium command throughout the previous decade - but Hannibal would soon be forced to return to Africa and defend Carthage against Scipio Africanus' attacks. Carthage's long war with Rome would end in defeat at the Battle of Zama in 202 BCE. Marcellus' reputation and fame would continue well beyond his own death. Livy was a little critical, suggesting the commander was rather pedantic and too superstitious, but Plutarch gives a more glowing character portrait, albeit one meant to fit in his scheme of parallel biographies with Greek commanders. Still, Marcellus' successes in Gaul and the taking of mighty Syracuse are undisputed history. In addition, as one of Rome's great commanders and a symbol of honourable leadership, his campaigns against the Gauls were cited in the Augustan fasti records two centuries later as the epitome of Roman virtue.