Mari was a city-state located near the west bank of the Euphrates River in Northern Mesopotamia (now eastern Syria) during the Early Bronze Age and the Middle Bronze Age. One of the earliest known planned cities, Mari is believed to have been founded as a trade hub, and copper and bronze-smelting centre, between Babylonia in Southern Mesopotamia and the resource-rich Taurus Mountains of modern Turkey. For 1,200 years, Mari served as a major centre of Northern Mesopotamia until it was destroyed by Hammurabi of Babylon between 1760 BCE and 1757 BCE and gradually eroded away from memory and quite literally - today only one-third of the city survives with the rest washed away by the Euphrates.

Geography & condition of the site

The ruins of Mari are located at modern-day Tell Hariri in eastern Syria. In the Bronze Age, the Euphrates was around 4-6 km from the city but has since moved farther east. The city is believed to have been constructed along with a 10 km long man-made "linking canal" that once cut through the city and provided water essential for the city's existence as the city itself was too far from the Euphrates for daily water retrieval on foot and the ground water is too salty for wells. As a result of the destruction of Mari by Hammurabi, Mari's linkage canal expanded outside of its intended boundaries and eventually eroded away two-thirds of the city, including most of the housing from the third and last phase of the city.

Canals: the life-blood of Mari

In addition to providing water for the city, the linkage canal also gave easy access for trading ships travelling on the river. Along with the linkage canal, two other substantial canals were constructed by the city's builders. One was an irrigation canal, 16 km long and 100 m wide, and the other was a 126 km long navigational canal which ran past Mari on the opposite side of the Euphrates and allowed boats to bypass the winding Euphrates in favour of a straight passage - Mari controlled the entry points and profited from tolls.

Technological & architectural innovations

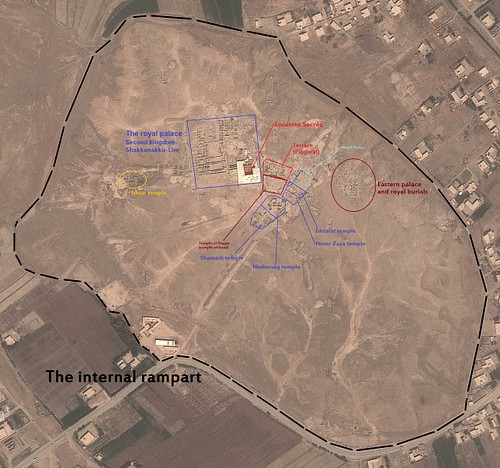

Mari is an early example of complex urban planning and is believed to have been entirely planned out prior to its actual construction by another unknown but complex society. This is evident in Mari's overall design as the city was built as two concentric rings, the outer ring intended to protect the city from the occasional violent floods of the Euphrates, and the inner ring designed to defend against attackers.

The earliest examples of certain Syro-Mesopotamian technologies were excavated by archaeologists at Tell Hariri, including the wheel and plumbing. Mari was built so that the whole city sloped gradually downwards, and the streets had complex drainage systems. This meant rainwater from the occasional torrential rains could be safely drained out of the city without risking damage to the buildings which were all made from mudbrick.

Archaeology & modern perils

Mari was discovered in 1933 CE by a local Bedouin who found a statue and informed the French government - this was a period when Syria was controlled by France. Since then, Mari has been a French-excavated site, with most of the literature on the site published in French. It was excavated by André Parrot from 1933–1939 CE, 1951–1954 CE, and 1960–1974 CE. In 1979 CE, a new expedition began under Jean-Claude Margueron, who ran the excavation until 2004 CE.

After he retired and gave his responsibilities over to Pascal Butterlin, Margueron went on to write a book on Mari, which compressed 70 years of scholarship on the site into a 159-page English-language summary, which forms the basis of this definition. Butterlin ran the excavations up to 2012 CE when the Syrian Civil War placed further excavation on hold indefinitely. Since 2012 CE, Mari has faced extensive looting, the impact of which is not yet known.

Mari tablets

Between 1933 CE and 1938 CE, excavators uncovered over 15,000 tablets at Mari. Many of these were concentrated in the "Great Royal Palace," but many also came from private homes. While some tablets are from an earlier period, most of the tablets are from the last 50 years of Mari's existence, and these help to recreate the Syro-Mesopotamian world of the time in great detail.

History

Mari's history as a city and regional power lasted from c. 2950 BCE to 1760 BCE, and this 1,200-year history was divided into three major periods by Margueron: City I, City II, and City III. After Hammurabi laid waste to the city between 1760 BCE and 1757 BCE, it became a backwater. The following history is based on Margueron's conclusions about the likely foundation and existence of Mari, combined with other sources.

City I - A superpower is born

The earliest part of Mari's history, c. 2950-2650 BCE, was called "City I" by Margueron.

Between 3000 BCE and 2900 BCE, an unidentified, but well-organised, complex society selected an inhospitable area near a bend in the Euphrates River to build their new capital. They likely wished to corner the market in trade and metal goods production in Northern Mesopotamia. After digging a canal to connect two bends of the river, they used the earth from this to raise a perfectly circular area that would form the heart of their new city and through which this canal passed, making the uninhabitable location habitable. Fortifications were constructed, and a grand capital enclosed within two concentric circles took shape, a design it would retain for its entire 1,200-year history.

Along with the construction of the linking canal, these people built two other canals on either side of the city. The eastern one on the eastern side of the river was a navigation canal. The other was an irrigation canal to feed Mari's crops.

As of 2008 CE there had been no religious or palatial structures found from City I. Many houses were found, however, and excavations of these houses paint a picture of a city filled with a vibrant and varied industry producing goods far beyond those made of metal.

At some point, c. 2650 BCE, City I ceased to be inhabited for reasons unknown. Over the next century, the canals silted up and the city lay empty.

City II - Mari reborn

In c. 2550 BCE, a new city was founded over the ruins of City I, which were levelled by the new inhabitants, hence the lack of evidence for the end of City I. The new inhabitants completely rebuilt over the old plan of the city and re-dredged the canals.

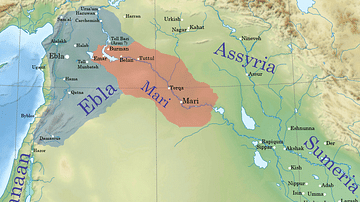

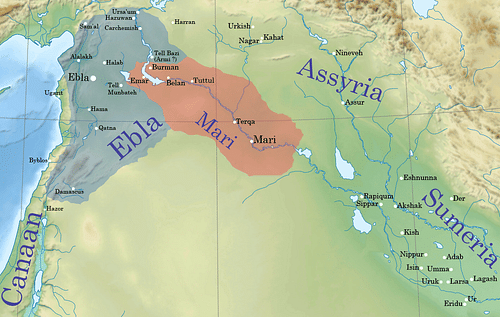

Much of the historical knowledge of Mari from this period, called "City II" by Margueron, is informed by texts found at the site of Ebla, Mari's on-and-off rival and ally. Mari is known to have controlled a significant portion of Northern Mesopotamia, and during the reign of Ishbi-Irra, it may have even controlled territories as far south as Ur in what is now southeastern Iraq and which was then a coastal city. Sometime in the latter half of the 25th century BCE, Mari and Kish are known to have been allied with Zuzu of Akshak in his unsuccessful campaign against Eannatum, King of Lagash.

From c. 2420 to c. 2360 BCE, Mari exacted tribute from Ebla, starting during the reign of Iblul-Il of Mari. This ended when a dispute over lands held by Mari on the eastern side of a bend in the Euphrates River escalated into a war which eventually ended in Mari's favour. However, Ebla managed to string together a northern trade route of friendly cities north of Mari's holdings and thus avoided having to rely on Mari for goods from the East. The rivalry between Mari and Ebla ended with the destruction of Ebla c. 2350 BCE.

City II was destroyed by the Akkadian King and grandson of Sargon, Naram-Sin. Naram-Sin sought to expand the Akkadian Empire, and c. 2220 BCE, he razed the city and its walls.

City III - Mari the Great & the Empire in the North

Mari was rebuilt under the Akkadians, and this incarnation of Mari is classified by Margueron as City III. Local governors called Shakkanakku controlled the city, and this administrative title became a hereditary title after the first ruler.

When the Akkadian Empire fell, c. 2150 BCE, Mari became independent once more and regained dominion over Northern Mesopotamia. The use of the Shakkanakku title continued despite Mari's freedom and was used for the rest of City III's existence.

For the first 150–200 years of City III's existence, the Shakkanakku lived in a palace for which the only details known are its existence and location, and that it and some temples were the first structures rebuilt following the destruction of City II. The lack of information results from the razing of this so-called "phantom palace" to make way for the "Great Royal Palace," a massive structure of over 250 rooms on just the ground floor.

In order to maintain peace in the region, Mari allied itself with Ur's Dynasty III, which controlled Southern Mesopotamia, and Mari cemented this through royal marriages. This peace continued until Ur's dynasty crumbled c. 2000 BCE, as a result of Amorite incursions and internal decay, and the south fell into chaos.

Around 2000 BCE, nomadic Semitic peoples known as Amaru or "Amorites" invaded from Syria and took control of the cities of Mesopotamia. Mari is known to have reinforced its walls in an effort to keep the Amorites out, but by c. 1830 BCE, this proved futile and the Shakkanakku fell.

Amorite Period

Around 1830 BCE, the Amorite ruler, Yaggid-Lim took control of Mari and replaced the "Shakkanakku Dynasty" with one referred to today as the "Lim" or "Amorite Dynasty." With a notable period of interruption, the rule of Yaggid-Lim's descendants lasted until 1761 BCE. The archive of inscribed clay tablets from Mari dates from this time, and as a result, many key historical actors and stories are known. The tablets help paint a picture of the political, economic, and social landscape of Mari in its last years, as well as in the wider world around Mari.

During his ten-year reign, Yaggid-Lim is known to have run afoul of the king of Ekallatum who conquered Mari and took Yaggid-Lim's son, Yakhud-Lim, hostage. In 1820 BCE, Yaggid-Lim died, and his son, Yakhud-Lim took the throne. Yakhud-Lim sought to increase Mari's influence both economically and militarily. Along with expanding Mari's already impressive irrigation systems and reinforcing the fortifications of Mari and Terqa, he also sent forces as far west as the coastal cities in the Levant and forced them to pay tribute to Mari.

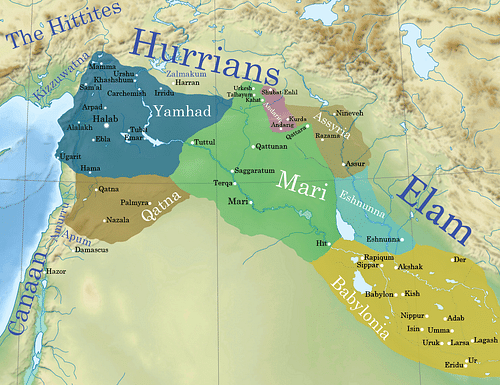

Despite these efforts, Mari under Yakhud-Lim became a vassal of Aleppo, but at one point was forced to become a vassal of another Naram-Sîn, this time of Eshnunna. Naram-Sîn died c. 1811 BCE, and Mari once more became independent and began to regain its old territory. However, this was not the end of Yakhud-Lim's troubles.

Amorite intrigues & the "Assyrian" Kings

Around 1808 BCE, Shamsi-Adad, who would be retroactively counted as a King of Assyria by later Assyrian kings, began conquering Northern Mesopotamia when he took control of Assur. When Shamsi-Adad's ambitions became apparent, a war erupted between him and Yakhud-Lim for control of the region. After a time, Yakhud-Lim lost and was later assassinated by his own son, Sumu-Yamam, c. 1798 BCE, who ruled Mari for two years before being crushed by Shamsi-Adad in 1796 BCE. Shamsi-Adad's son and co-ruler, Yasmakh-Adad was given rule over Mari at an uncertain date, possibly c. 1788 BCE.

Letters between Yamsakh-Adad and his father show that Yamsakh-Adad was an extraordinarily ineffective and dissolute ruler and that he had to call on his father - who showed a deep disdain for his son - frequently for assistance. A ruler named Zimri-Lim, who was a grandson or nephew of Yakhud-Lim, defeated Yamsakh-Adad with the help of Aleppo in 1776 BCE, after Shamsi-Adad's death, and retook the throne for the Amorite Dynasty.

Zimri-Lim: the last King of Mari & the end of Mari

Zimri-Lim sought to reclaim Mari's old glory, and after spending five years settling tribal disputes and battling with the Kingdom of Eshnunna, whose alliance Zimri-Lim had dismissed in favour of one with Aleppo. He cemented an alliance with Aleppo with a marriage to the king's daughter.

Mari is known to have been very tribal at this time - with the bulk of Marians calling themselves "Khanaeans", a reference to the Amorites' origins - and there are several known instances when the palace-bound Amorite rulers are known to have had conflicts with their fellow, nomadic Amorites. Zimri-Lim is known to have lived a life of splendour.

Around 1766 BCE, a coalition of Babylon, Mari, and Elam captured Eshnunna, but Mari and Babylon were betrayed by Elam, which they later managed to rebuff. Afterwards, though Zimri-Lim and Hammurabi of Babylon did not trust each other, the two frequently campaigned together against many powerful enemies.

In 1761 BCE, Hammurabi - once an ally of Zimri-Lim - captured Mari. It is not known what became of Zimri-Lim, whether he had been betrayed by Hammurabi or died on a military campaign. It is also unknown whether Mari was taken by threat of force - there is no evidence of this or that Mari was preparing to defend itself - or, finding itself leaderless, the city simply gave itself over to Hammurabi who then sent emissaries to seize the riches of the Great Royal Palace over a period of two years. Regardless, sometime between 1759 and 1757 BCE, Hammurabi razed Mari to the ground.

When Hammurabi burned the palace, he unintentionally baked the tablets inside - an event that has occurred in several ancient cities, such as Ebla and Ugarit, where the palace becomes an unintended pottery kiln - thus preserving the tablets for future excavators of the site. Mari never recovered from this destruction, and the city fell into obscurity. The site saw only occasional habitation until the time of Alexander the Great's successors when it was finally abandoned for good.