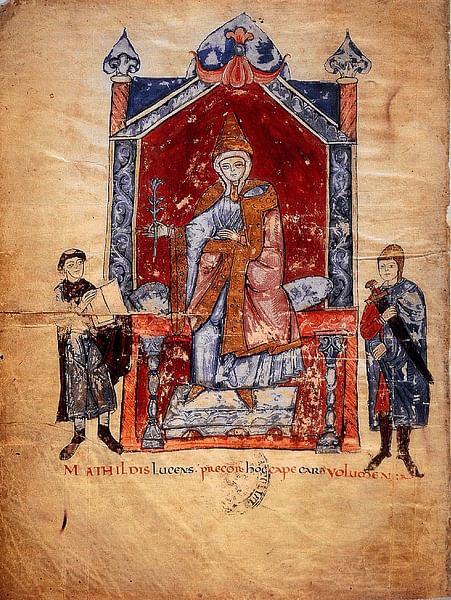

Matilda of Canossa (c. 1046-1115), the Countess of Tuscany (r. 1055-1115) and Vice-Queen of Italy (r. 1111-1115), was the final head of the noble House of Canossa following the deaths of her father in 1052 and her elder brother in 1055. One of the most influential women of medieval Europe, Matilda is noted for her military and political prowess, her ceaseless patronage of the Christian Church, and her defense of Papal authority. Though a vassal of the Holy Roman Empire, Matilda often acted independently. Her conflict with the imperial state included a nearly lifelong military conflict with Henry IV (1050-1106), the German king (r. 1056-1105) and Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1084-1105).

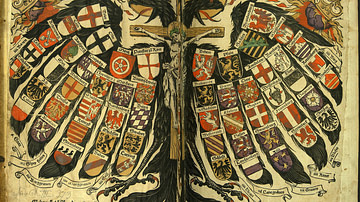

Most of Matilda’s holdings, including her family’s ancestral castle of Canossa, were located across the plains of the Po Valley in northern Italy, an invaluable intersection of trade routes between the Italian peninsula and Italy’s northern neighbors beyond the Alps. In the southern part of Matilda domain beyond the Po Valley was the Duchy of Tuscany, rugged with mountains in its north, rural hills throughout, and vital roads connecting to Rome. With these possessions and an impenetrable alliance with the Christian Church, she became an influential political figure in medieval Europe. Matilda was often referred to as the Great Countess (la Gran Contessa) by contemporaries and scholars, despite this title being lesser than her truer title, that of the Margravine of Tuscany. Although she was considered the rightful heir to her father’s northern Italian holdings, Henry IV never recognized her claims to the lands within the Holy Roman Empire.

Early Life

Matilda was a descendent of the House of Canossa, a noble family established by her great-grandfather Atto Adalbert of Lucca (d. 988), a 10th-century Lombard military leader from Lucca and vassal to the German kings of Italy. Adalbert and his son Boniface expanded their domain and by 1027, the Canossa family's influence encompassed the counties of Brescia, Cremona, Ferrara, Mantua, Modena, Reggio Emilia, and Veneto. In 1027, Roman Emperor Conrad II (r. 1027-1039) transferred the Duchy of Tuscany to Boniface. As Schevill explained,

With Tuscany added to his strength ... Boniface completely dominated central and northern Italy; and since he clung to his superior, the emperor, with more consistency than was usual among feudal magnates, he served as the main pivot of the imperial power in Italy in his day. (53)

In 1037, Boniface married Beatrice of Lorraine (c. 1020-1076), a direct descendent of Charlemagne and Conrad’s niece by way of marriage. Matilda was born to Boniface and Beatrice in 1046 after two older siblings: Frederick and Beatrice. Matilda’s place of birth has been disputed, though scholars have suggested Canossa, Lucca, and Mantua. On 6 May 1052, when Matilda was six years old, Boniface was killed by an unknown assailant, likely by an assassin of Holy Roman Emperor Henry III (r. 1046-1056). Frederick inherited the feudal land of their father while Beatrice governed on his behalf. Matilda’s older sister died shortly after Boniface in 1053, though details are unclear.

In 1054, Beatrice married her first cousin Duke Godfrey the Bearded of Upper Lorraine, while Matilda was betrothed to the elder Godfrey’s son, Godfrey the Hunchback. Although Pope Leo IX, another cousin of Beatrice, gave them his blessing to marry, neither received consent from their king, Henry III.

Using the marital transgression to his advantage in 1055, Henry imprisoned Beatrice and Matilda at Bodfeld in current-day central Germany and claimed their holdings. Frederick, the only son and heir to Boniface, is thought to have died in 1055, leaving the young Matilda as the sole child of the Canossa dominion. Since women did not have the right to own, govern, or inherit feudal land under imperial law, Frederick’s death made not Matilda but Henry III, Beatrice’s closest adult male kin, the rightful heir to Boniface.

The mother and daughter remained in captivity until Henry III suddenly died in October 1056. Until the adulthood of Henry’s heir, Henry IV, the widowed Queen Agnes acted as regent to the young king. In exchange for a renewed oath of fealty from Godfrey the Bearded, Agnes freed her deceased husband’s prisoners and authorized the marriage of Godfrey and Beatrice. Godfrey, therefore, controlled the Canossa holdings and established his court in the Duchy of Tuscany, where the family returned by the spring of 1057. Information concerning Matilda’s youth beyond these events is terse.

The marriage of Beatrice to Godfrey the Bearded remained intact despite Henry III’s efforts and was recognized by Queen Agnes. Matilda’s inheritance in Italy was passed to the governance of her stepfather, who, in 1064, also inherited the Duchy of Upper Lorraine. With her role as heir forfeited to her stepfather, Matilda abandoned her ancestral home in Italy in favor of her husband’s in Upper Lorraine. The betrothal to her cousin Godfrey the Hunchback was not fulfilled by marriage until May 1069 when Matilda was 23 years old and the elder Godfrey was expected to die after falling ill. Upon his death, the titles in Italy and Lorraine were transferred to the younger Godfrey. The only child of Matilda by Godfrey was Beatrice, named after her grandmother, but she died shortly after birth, sometime between May and August 1071.

Papal Alliance & the Investiture Controversy

Matilda returned to Italy without Godfrey and governed alongside her mother from their court at Mantua and presided over the land despite Godfrey’s inheritance of the domain. Matilda maneuvered over the following years to establish her influence in Italy with aid from her close ally, Hildebrand of Sovana (c. 1015-1085). Matilda had a strong personal relationship with Hildebrand, who was elected Pope Gregory VII in April 1073 CE. Matilda and Hildebrand in all accounts were the strongest of allies, and suggestions of their scandalous intimacy flourished. Whether or not the pair were intimate, the leader of Christianity and upholder of the medieval legal patriarchy turned a blind eye to Matilda’s abandoned marriage.

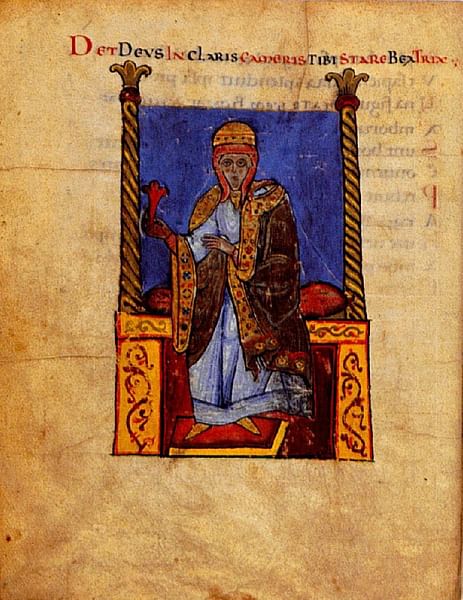

Throughout her life, Matilda sought to strengthen the authority of the Christian Church and the Papacy. Her formidable alliance with Gregory VII established a significant impediment to Henry IV’s dominance, and through the pope’s reform policies, known as the Gregorian Reforms, the Italian pair challenged the legal authority of her feudal lord and the Holy Roman Empire. The assertions of papal superiority over secular states ushered in a conflict between Gregory and Henry known as the Investiture Controversy. In 1074, Gregory disqualified members of the clergy who obtained office by secular appointment (investiture) and asserted that the clergy could only be appointed by the sitting pope, thereby removing the direct influence of the Holy Roman Empire in church jurisdictions. In December 1075, after months of political retribution, Henry IV sent armed envoys to Rome to imprison Gregory, only for the pope to be rescued by loyalists.

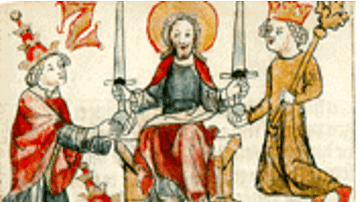

On 26 January 1076, Henry IV convened the Synod of Worms, during which an assembly of loyalists condemned the pope, nullified their allegiances to him, and demanded his resignation. Matilda’s estranged husband Godfrey the Hunchback remained loyal to Henry IV and attended the assembly at Worms, where he publicly accused Pope Gregory VII and Matilda of adultery. On 22 February, Gregory, with Matilda by his side, excommunicated and deposed Henry IV, releasing his vassals from their feudal contracts and prohibiting Christians from following his commands. Henry IV’s highest supporters followed the excommunication with an ultimatum: submit to the pope or abdicate.

On 26 February 1076, Godfrey was assassinated. Before he took his final breath, Godfrey the Hunchback disinherited Matilda by bequeathing his possessions to his nephew, Godfrey of Bouillon. Beatrice, governing the northern Italian lands, revived the civil law code of Emperor Justinian I (r. 527-565), citing his Digest to provide a legal basis for the inheritance to pass not to Godfrey of Bouillon but to her daughter. Accusations of Godfrey’s murder were charged to Matilda, who then mourned the death of her mother on 18 April 1076.

In September, the opposition leaders within the Holy Roman Empire requested Gregory VII’s attendance at an assembly in the coming winter to elect a new Holy Roman Emperor. In December, upon Matilda’s suggestion, Gregory VII accepted the invitation and began the journey to the assembly at Trebur, with Matilda alongside him.

The Walk to Canossa

In early January 1077 CE, Henry IV crossed the Alps into Lombardy with an army escorting him. Matilda and Gregory VII, upon news of his approach, rerouted to Matilda’s castle at Canossa. After arriving shortly before Henry IV, Matilda and Gregory VII watched the penitent Henry arrive at the Canossa’s walls seeking papal absolution.

The events that followed atop a mountain ridge crowned with Matilda’s medieval fortress have been immortalized as the Walk to Canossa. Matilda, the mediator of this encounter, greeted her royal cousin as he pled for papal absolution in the frozen winter snow of northern Italy. Within the castle, Gregory VII absolved Henry in exchange for the emperor’s submission to the Church. Henry obliged, though he later contradicted his promise and was denounced once more. Henry’s act of penitence, however, strengthened Gregory’s pursuit of creating a religious authority greater than that of secular kings. The balance of medieval European politics had been tipped at Canossa: the Holy Roman Empire descended into civil war in March, with Henry’s opposition faction having continued with its selection of Duke Rudolf of Swabia as his replacement.

Civil War

Later in 1077, Matilda relocated to Rome along the Tiber. As civil war engulfed the empire, she and Gregory VII aligned themselves with Rudolf’s rebellious faction of nobles. The pope issued a second excommunication to Henry IV in 1080, to which the German king again denounced the pope citing, among other things, his alleged adulterous transgressions with Matilda. As Henry’s military moved towards Rome to defeat the Gregorian opposition, Matilda fled to Canossa. Many of her vassals rejected her call to war against the emperor, who posed an imminent existential threat as he marched on Rome. The German army besieged the city from May 1081 to March 1083 when Gregory VII was captured. Giuberto, the bishop of Ravenna, was installed as Pope Clement III (r. 1080-1100), and he confirmed Henry IV as Holy Roman Emperor.

Henry IV, Clement III, and their army were pushed out of Rome in May 1084 by the advancing soldiers of Robert Guiscard (c. 1015-1085), the Norman duke of Apulia, Calabria, and Sicily. No longer occupied by the imperial army, Guiscard’s military sacked and pillaged the city. Gregory VII was liberated, but he remained deposed in favor of Clement III. He spent the next year exiled in Salerno to the south where he died on 25 May 1085.

The war with Henry IV severely damaged Matilda’s financial and military power. Although her holdings remained within the Holy Roman Empire, Matilda was never recognized by Henry IV as a feudal landlord of any possessions. Despite being unrecognized, disinherited by Godfrey, and having lost her dearest friend in Hildebrand, Matilda continued to govern.

In July 1085, she rejected a marriage proposal from Duke Robert of Normandy, the son of William the Conqueror. The union with the Norman rulers of England could have supplied the military strength to renew her fight against Henry IV. Reluctant to remarry, she chose independence. Matilda opposed the election of Pope Victor III (r. 1086-1087), an opponent of the Gregorian movement, and initiated the search for a successor to the Gregorian line to oppose the German papacy of Clement III. At the prompting of Matilda, an assembly of bishops elected one of Hildebrand’s chosen successors, Bishop Odo of Ostia (r. 1088-1099).

Odo, now Pope Urban II, became a close ally of Matilda and attempted to emulate Hildebrand’s papal philosophies. At Urban II's calculated suggestion in 1089, Matilda married Welf V of Bavaria (c. 1072-1120) whose father maintained a strong army in their domain to the northeast of Italy, opposed the authority of Henry IV, adhered to the leadership of Gregory VII, and rejected the papacy of Clement III, making the Bavarian house an ideal ally for Matilda.

Campaign Against Henry IV

Emperor Henry IV returned to Italy in 1090 to silence Pope Urban II and his openly-rebellious vassals, including the insurgent Matilda. Henry’s imperial army marched south, capturing much of Matilda’s Po Valley holdings. Though peace was offered to Matilda by Henry IV, entailing her submission to his authority and to Clement III, she rejected it outright. In October 1092, Henry’s military marched on Canossa and its surrounding fortresses. Matilda, the intelligent strategist, guided her small army at Canossa to a swift victory. Henry’s Lombard loyalists in Cremona and Milan repudiated their allegiance to the emperor following the retreat and agreed to a military alliance with Matilda. The coalition of Matilda in the south, the Lombards to the west, and the Bavarians to the northeast trapped Henry in Verona at the base of the Alps. Clement III joined the king at Verona to celebrate a Christmas mass and was unable to return to Rome through the military barrier, leaving the Holy See in the hands of Urban II.

In 1093, Matilda and the Gregorian alliance supported the rebellion of Henry’s son and heir Conrad (c. 1074-1101) against the emperor. The king of Italy since 1087, Conrad controlled much of northwestern Italy outside of Lombardy. In 1094, Henry’s second wife Eupraxia of Kiev, known by the German name Adelaide, fled and publicly denounced Henry IV as abusive and adulterous. Henry ascribed his family’s betrayal to the manipulations of his old rival Matilda, who sheltered Adelaide at Canossa and propagandized Adelaide’s desertion to garner wider support.

With Henry IV weakened and confined to northeastern Italy, the marital alliance of Matilda and Welf V had served its purpose and was annulled by Urban II in 1095. Henry, after negotiations with Duke Welf V, returned to Germany in early 1096. Shortly after his return, Henry IV disinherited Conrad and chose his second son, also Henry, as his next in line.

The First Crusade & Later Years

In November 1095, at the behest of the Byzantines, Pope Urban II decreed the launch of the First Crusade (1095-1102) to recapture the holy city of Jerusalem from Muslim control. Years earlier, Matilda supported Pope Gregory VII’s advocacy for Christian intervention in the eastern Mediterranean against Muslim influence. The devout Matilda of Canossa had maintained her ardent support for the Gregorian supremacy of the Church and its imperialism for the rest of her life, and Urban’s call to war was no exception. After repulsing the imperial army from Italy twice, Matilda had earned her reputation as one of the strongest European leaders of her time.

Throughout her life, Matilda supported the Church, and her twilight years proved no different as she continued to fund the construction of churches and acquisition of new land. In 1102, Matilda willed all of her property to the Papacy "in the person of Pope Gregory" (Spike 227), which allowed the Church to claim all of her property, including her holdings and castles, after her death. From 1101 to 1103, Matilda organized the seizures of Ferrara and Parma from loyalists of Henry IV. Around the same time and until just shortly before her death, Matilda "released citizens from feudal obligations and taxes" in many towns throughout her domain (Spike 221-222). These holdings would be included among her land donations to the Church.

Henry V, after ascending to the leadership of the Holy Roman Empire, demanded to be crowned as such by Pope Paschal II (r. 1099-1118). The German king marched his army on Rome from the Alps in 1109, arriving without Matilda’s intervention. After months of deliberation, Henry V was indeed crowned emperor in 1111. Matilda met with her enemy’s son at Canossa, where she was named the vicar of Liguria and given the enigmatic title of Vice-Queen, reinforcing her legitimacy as feudal heir to Boniface while doing the same for the credibility of Henry’s claim to her land.

Conclusion

Matilda of Canossa died on 24 July 1115. After her death, Henry V claimed her northern Italian possessions, while the Church claimed the Duchy of Tuscany. Some local leaders in her lands, citing Matilda’s release of towns from their feudal obligations, used the vacuum of power to establish a variety of city-states free of both imperial and church control. In the centuries following Matilda’s death, many northern cities, including Florence, Genoa, and Pisa, maintained or fought to maintain governments independent from the Church and their surrounding kingdoms.

Matilda’s reputation and influence endured well beyond her death. The reforms of Gregory VII, fostered by Matilda, altered the structure of the medieval Church for centuries to come. Scholars have suggested the Florentine writer Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) used Matilda as a model for the character of the same name in his Purgatory. Matilda’s body was exhumed from its original resting place in Mantua and reinterred at the newly constructed Papal Basilica of St. Peter in the Vatican in 1645, five centuries after her death. Her body still rests at the heart of the Church, the organization she committed herself to in life.