Matthew Flinders (1774-1814) was an English navigator and hydrographer. He was the first person to map the coastal outline of Australia in 1801-1803, following his circumnavigation of the 7.692 million square kilometres (2.96 million square miles) continent. To Dutch navigators, the landmass was known as New Holland (specifically, the western and northern coastline), but for centuries, the unknown southern land had been referred to as Terra Australis Incognita. Flinders gave shape to Australia, revealing it to the world through his charts and maps, and has been given credit for suggesting the name 'Australia'.

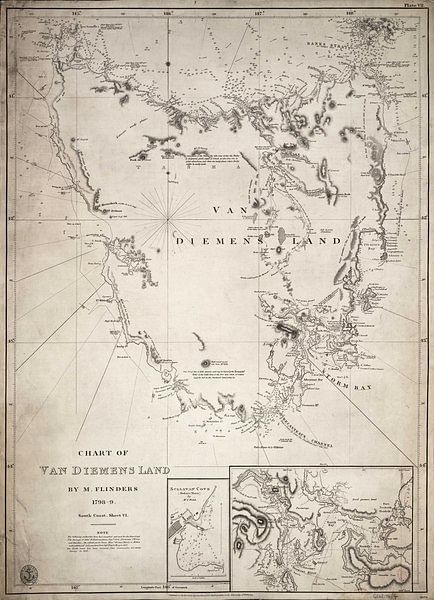

With his good friend George Bass (1771-1803), who was a British explorer and naval surgeon, Flinders circumnavigated Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) in 1798, proving it to be separate from mainland Australia. The strait that separated Van Diemen's Land from the mainland had first been detected by the Dutch navigator, Abel Tasman (1603-1659) in 1642, but Bass and Flinders confirmed its existence, and it was named 'Bass Strait'.

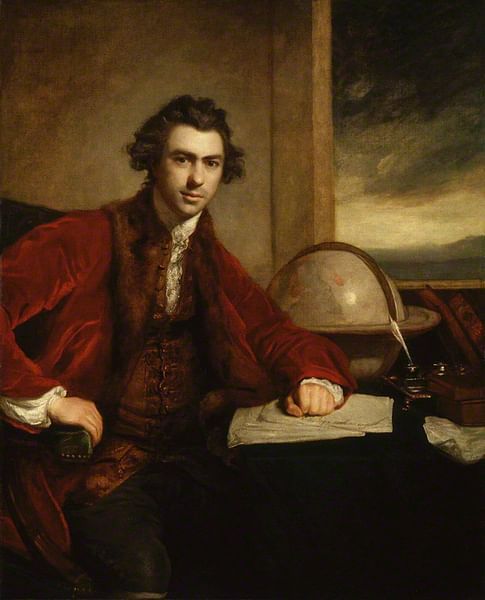

Flinders' passion for the sea and exploration led him to serve as a midshipman on board the Providence, commanded by Captain William Bligh (1754-1817), on a voyage from Tahiti to Jamaica, transporting breadfruit. Flinders was strongly supported by the famous botanist Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820), who convinced the British Admiralty to fund Flinders' expedition to accurately chart the Australian coastline. In 1803, while forced to repair his ship the Cumberland on a return to England, Flinders was detained for nearly seven years on Ile-de-France (Mauritius) and accused of being a spy.

Matthew Flinders' important contribution to Australian history is well-known to generations of Australian schoolchildren but was largely forgotten in his homeland. 40 years after his death, the location of his gravesite was no longer known, and it was not until January 2019, during burial ground excavations, that his gravesite was identified.

Early Life

Matthew Flinders was born in the market town of Donington, Lincolnshire, north of London, on 16 March 1774, to Matthew, a surgeon-apothecary, and Susannah Flinders. Although his father expected his son to follow the family tradition of becoming a doctor, from an early age, the younger Matthew had been enthralled with Daniel Defoe's (d. 1731) daring tale of Robinson Crusoe and dreamed of distant lands waiting to be discovered. Flinders later wrote:

I burned to have adventures of my own. I felt as I read that there was born within my heart the ambition to distinguish myself by some important discovery. (quoted in Scott, ch. 2)

He was largely self-taught, having studied Greek classics, navigation techniques, and Captain Cook's voyages of discovery. A cousin, who was the governess for the family of Captain Thomas Pasley (1734-1808), a highly regarded British Royal Navy officer, had mentioned Matthew's ambition to go to sea, and Pasley was impressed by the young man's wealth of knowledge.

Flinders enlisted in the Royal Navy in 1789 at the age of 15, and Pasley secured for him the position of a lieutenant's servant aboard HMS Alert. Flinders also served as a crew member under Pasley's command on HMS Scipio and learn the practical skills of being a sailor before becoming midshipman on the famous 74-gun fighting ship HMS Bellerophon in 1790. Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) would later surrender to Captain Frederick Lewis Maitland (1777-1839) aboard the Bellerophon in July 1815, following the Battle of Waterloo.

These postings, however, did not provide much in the way of sea time, but the chance to sail to remote places came in 1791 when Matthew Flinders was transferred to the Providence under the command of Bligh. Captain William Bligh, who had sailed with Cook, was a national hero in England. Bligh had been in command of HMS Bounty when it sailed to Tahiti in December 1788 with instructions to collect breadfruit as food for West Indian plantation slaves.

Some of Bligh's crew considered his leadership 'tyrannical,' and in April 1789, three weeks after leaving Tahiti, what became a legendary mutiny was led by master's mate Fletcher Christian (1764-1793). 21 crewmembers cast Bligh and 18 loyal crew adrift in the Bounty’s launch, a seven metres (22 feet) longboat. What the mutineers did not count on was Bligh's remarkable seamanship. He navigated more than 6,500 nautical kilometres (3,500 nautical miles) through high seas to Kupang in Timor, a voyage that took 48 days and necessitated a difficult passage through the Torres Strait, which separates Australia's Cape York Peninsula from Papua New Guinea. Flinders later sailed through the Torres Strait with Bligh. Nine mutineers made it to Pitcairn Island, a remote volcanic island in the south-central Pacific Ocean, and direct descendants live there today.

Sailing with Captain Bligh

The British Admiralty and Sir Joseph Banks (patron of Kew Gardens and president of the Royal Society) approved Bligh's second breadfruit expedition in March 1791 and also instructed him to navigate and chart Torres Strait more closely. Safe passage through the narrow, treacherous strait – a complex of reefs, islands, and shoals – would save around six weeks on a voyage from the new British penal colony at Sydney Cove, Port Jackson (New South Wales) to India or England. The alternative longer route was to sail around the northern coast of New Guinea.

The Providence and the Assistant (a companion ship) arrived in Adventure Bay, Van Diemen's Land in February 1792, where Bligh conducted surveys and had the ship's botanists plant fig and pomegranate before leaving for Tahiti to collect 600 breadfruit plants to take to St. Helena in the Caribbean and to the West Indies. Flinders drew a chart of the passage through Torres Strait, which took 19 days for the Providence to navigate through, and the crew had to fight off hostile Torres Strait islanders in canoes along the strait.

Flinders was meticulous at keeping journals, and he noted that on the run from the Pacific to the West Indies, there was a shortage of water. Bligh ordered the breadfruit plants be watered first, and Flinders and the crew had to resort to licking droplets from the watering cans. Nevertheless, on the voyage with William Bligh, Flinders gained tremendous knowledge about water rationing, how to ward off scurvy, and he honed his navigational and astronomical observation skills. Bligh had enough confidence in the then-18-year-old to assign him the task of winding the chronometers and recording the times at noon each day to ensure accurate time as the ships sailed through different longitudes.

The Providence and the Assistant returned to an England preparing for war in August 1793, amid the throes of the French Revolution, and Flinders took the opportunity to report to Pasley, who was commodore on the Bellerophon and part of the Channel Fleet under Lord Howe's (1729-1814) command.

A Taste of War & Bound for Australia

Pasley invited Flinders to be his aide-de-camp (personal assistant) onboard the Bellerophon, which patrolled the seas around England, protecting the country against enemy ships after France had declared war on Great Britain on 1 February 1793. The Bellerophon saw action in May 1794 when it spotted the French fleet and attacked the first-rate 110-gun Revolutionnaire, which lowered its colours several hours later when it was defeated.

Flinders only spent five days at the battlefront during what is known as the Glorious First of June – the first major naval battle in the war with Revolutionary France. Pasley was severely injured during a skirmish with the Éole, losing a leg from an 18-pound shot, and would never sail again. It had a profound effect on Flinders' career, for had Pasley obtained further sea commands, Flinders might have joined him as the two were close. Flinders was to meet the French again, but before doing so, joined the discovery vessel HMS Reliance that was preparing to sail to the Port Jackson penal colony. Onboard was Captain John Hunter (1737-1821), who had served during the Glorious First of June on the flagship Queen Charlotte and had been appointed as the second governor of New South Wales.

Flinders most likely learnt about the opportunity to return to the great southern land from his Bellerophon shipmate, Henry Waterhouse (1770-1812), who was given the position of second captain on the Reliance. Flinders' younger brother, Samuel Ward Flinders (1782-1834), who had been allowed to join the navy by their father, would also sail on the Reliance.

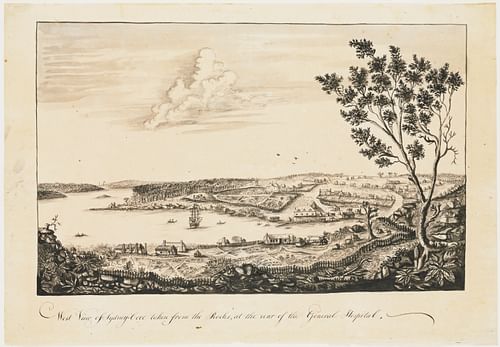

The ship arrived at Port Jackson in September 1795, nearly three years after the first governor, Arthur Phillip (1738-1814), had departed. Hunter found himself having to gain control of the New South Wales Corps - a permanent regiment of the British army also known as the Rum Corps because the currency of the colony had become rum. Control of the colony was firmly in their grip.

In late October 1795, while the Reliance was being refitted, Flinders set off in a small boat called the Tom Thumb to explore and survey Botany Bay (south of Port Jackson) and the Georges River, a major tributary that flowed into the bay. He was accompanied by George Bass, who was the ship's surgeon and also from Lincolnshire. The Tom Thumb "was a little boat of about eight feet keel and five feet beam" (Scott, ch. 6), and in March 1796, Bass and Flinders extended their surveying southward to the coastal area of the Illawarra (the location of modern-day Wollongong and Port Kembla).

The result of these voyages in a boat that was little more than the size of a bathtub was a refinement of the charts of New South Wales made by Captain James Cook, Hunter, and others. Flinders' report and charts were presented to Governor Hunter and dispatched to London, where the decision was made to establish a new settlement called Bankstown.

In early 1797, Flinders rejoined the Reliance and sailed to the Cape of Good Hope to obtain livestock for the colony at Port Jackson. Two things happened on this voyage: Flinders passed an examination to become a lieutenant, and he acquired a black cat called Trim, a feline that would sail with him for years to come. The Reliance returned to the colony in late June 1797, and Governor Hunter, who believed a passage existed between Van Diemen's Land and the southern coast of New Holland, gave Flinders command of the Norfolk, a sloop built by convict labour on Norfolk Island, 1,676 kilometres (1,041 mi) northeast of Sydney. Bass was part of the crew, and together, their circumnavigation and charting of Van Diemen's Land shortened the passage from England to Port Jackson by 555 nautical kilometres (300 nautical miles). Flinders recommended to Governor Hunter that the strait separating the island from the Australian mainland be called Bass Strait.

Return to England & Marriage

The Reliance left Port Jackson in March 1800 to return to England via Cape Horn with 26-year-old Flinders and his cat Trim aboard. Flinders' explorations had led to considerable recognition for the young lieutenant, and some of his charts had been published (and dedicated to Banks). He drafted a letter to Sir Joseph Banks, outlining the extent of his work and his desire to undertake a complete survey of the coast of New Holland, and wrote in his 1814 book, A Voyage to Terra Australis:

The plan was approved by that distinguished patron of science and useful enterprise [Sir Joseph Banks]; it was laid before Earl Spencer, then first Lord Commissioner of the Admiralty; and finally received the sanction of His Majesty, who was graciously pleased to direct that the voyage should be undertaken; and I had the honour of being appointed to the command. (quoted in Mundle, 214)

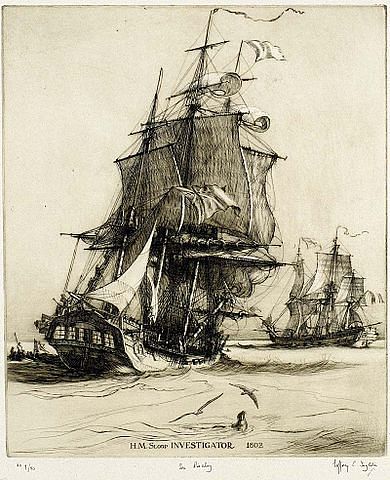

It was an attractive proposal since very little was known about the coastline of New Holland following Cook's survey of the east coast (1770). The French had also requested a passport from the British for a scientific voyage to New Holland under the command of Nicolas Baudin (1754-1803), who had instructions to explore the newly discovered Bass Strait. The East India Company was concerned the French wanted to establish a rival trade settlement in the southern hemisphere. So, Flinders was given the 22-gun sloop of war Investigator, a ship that would later prove to be in poor condition due to its conversion from a collier.

Sir Joseph Banks, a wealthy man, made sure the Investigator had the finest scientific equipment, but Flinders damaged his relationship with his mentor by marrying his childhood friend, Ann Chappelle (1772-1852), in April 1801. Flinders had intended for Ann to sail with him to New Holland, and she had moved into the captain's cabin. Banks read of the marriage in a local newspaper and quickly wrote to his protégé, telling him the Lords of the Admiralty were aware of the marriage and that it would be wise not to sail with his wife on board. Ann was sent to live with family, and Matthew Flinders did not see his wife or England for another nine and a half years.

The Investigator & Accusations of Espionage

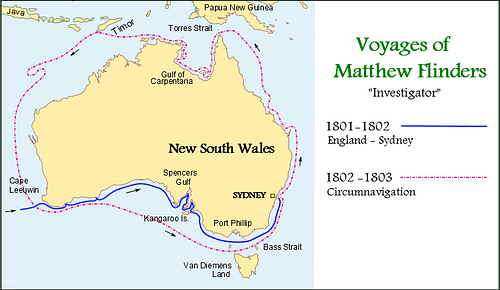

The Investigator left Portsmouth on 18 July 1801, with Flinders' beloved cat Trim aboard, and five months later, reached Cape Leeuwin (the most south-westerly point of the Australian continent). From 1801-1803, Flinders surveyed and charted King George's Sound, the Great Australian Bight, Spencer's Gulf, and Kangaroo Island before arriving in Port Jackson in May 1802. Flinders' surveying filled the gaps in Cook's charts and those of explorers like George Vancouver (1757-1798) and Antoine Bruni d'Entrecasteaux (1737-1793), who had partly mapped the western and southern coastline.

Flinders had an unexpected encounter with Baudin and his ship, Le Géographe, in Encounter Bay (South Australia), 55 nautical kilometres (30 nautical miles) north-west of Kangaroo Island. Their exchange was cordial, and they each presented their passports. Flinders' was made out in the name of the Investigator rather than its captain, and this would become a significant detail later.

After refitting in Port Jackson, Flinders charted the northeastern coast, Torres Strait, the Gulf of Carpentaria and Arnhem Land, arriving back at the settlement in June 1803, having completed the planned circumnavigation. The Investigator had been taking on water and Governor Phillip King (1758-1808), who took over from Hunter in 1800 as the third governor of New South Wales, sent Flinders home on the Porpoise so he could present his reports and charts to the Admiralty. The ship left in August 1803 only to be shipwrecked 1,296 nautical kilometres (700 nautical miles) north of Port Jackson. Like Bligh before him, Flinders and 13 crew had to make it back to the settlement over open sea in a cutter named Hope.

King then gave Flinders command of the Cumberland, which was locally built and designed for short coastal voyages. Flinders was forced to stop at Ile-de-France for repairs as the ship was leaking, but Flinders was not aware that England and France were at war. The governor of the island, General Decaen (1769-1832), a strong supporter of Napoleon Bonaparte, suspected Flinders was a spy due to his passport being for the Investigator and not in his name. Flinders also managed to insult Decaen by not taking off his hat in his presence or accepting a dinner invitation from Decaen's wife.

Flinders was arrested, and despite letters of support from Banks, he was incarcerated for nearly seven years. During this time, Trim disappeared, and Flinders' health deteriorated rapidly. Finally, in June 1810, Flinders, who now spoke fluent French, was released by Decaen and sailed on the Harriet, stepping foot on English soil once again in October 1810.

Flinders’ Final Years

Matthew Flinders did not return to the accolades he had hoped. Baudin's maps and charts had been published years before, and Flinders' reputation had faded. He spent the next three years preparing his charts and reports for publication. Matthew and Ann's only child, Anne, was born in April 1812 – she became the mother of the famous Egyptologist Sir William Flinders Petrie (1853-1942).

Matthew Flinders died in London on 19 July 1814, at the age of 40, one day after his two-volume work, A Voyage to Terra Australis, was published. Flinders had wanted to refer to 'Australia' in the title, and although Banks advised against it, the British Admiralty agreed in 1824 that the continent should be officially called Australia.

Flinders was a humble explorer, naming nothing after himself, but in Australia today, Matthew Flinders' contribution to Australian history is recognised by the naming of many landmarks after him, such as Flinders Ranges in South Australia, Flinders Street railway station in Melbourne, Flinders Chase National Park, and Flinders University.

With Trim as his companion, Flinders produced a definitive chart of the Australian coastline, and his research on wind strength and compass deviation led to the innovation known as the Flinders Bar, which is still used today – a soft iron rod placed vertically near a ship's compass to counteract variations caused by magnetism. On his many voyages, Flinders had observed how the presence of iron on a ship affected a compass.

The location of Flinders' grave in St. James's Garden, a former burial ground next to London's Euston station, was unknown by the mid-19th century, but it was rediscovered in January 2019 during excavations for a rail line. For the explorer who put Australia on the map, proposals have been made to honour Matthew Flinders' remarkable achievements with a reburial in his home village of Donington.