Medieval Castles were built from the 11th century CE for rulers to demonstrate their wealth and power to the local populace, to provide a place of defence and safe retreat in the case of attack, defend strategically important sites like river crossings, passages through hills, mountains, and frontiers, and as a place of residence.

Whether a permanent home for a local lord or a temporary one for a ruler embarking on a tour of their kingdom, medieval castles were converted from wood into stone and became ever more impressive structures with more and more defensive features such as round towers and fortified gates.

The Evolution of the Castle

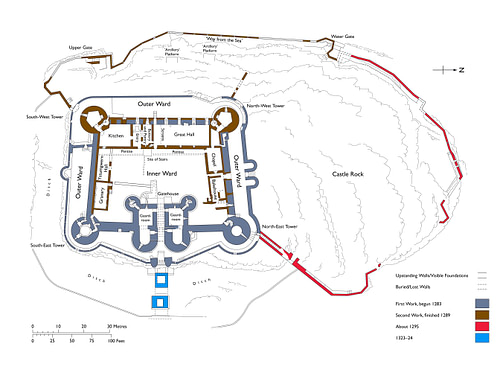

A good location for a castle was on a natural rise, near a cliff, on the bend of a river, or where older fortifications such as Roman walls could be usefully reused. Castles needed their own water and food supplies and usually a permanent defensive force, additional factors to be considered when choosing a location.

Castles were an expensive undertaking which could take years to finish. A master mason, who was, in effect also the architect, led a team of hundreds of skilled workers ranging from carpenters to blacksmiths and dyke specialists to common labourers. The transportation of materials was the highest cost of all so the proximity of a local quarry was a big plus.

The earliest form of castle was a simple wooden palisade, perhaps with earthworks, surrounding a camp, sometimes with a permanent wooden tower in the centre. This then evolved into the motte and bailey castle - a wall encircling an open space or courtyard (bailey) and a natural or artificial hill (motte) which had a wooden tower built on top of it. These were especially popular with the Normans from the 11th century CE.

In the next stage of development, an outer wall was built of stone on top of the motte and then known as a shell keep. Finally, in the 12th century CE, the outer wall and main central tower also came to be built of stone, but not usually on the motte itself as that was not stable enough to use as a foundation for such a heavy structure. Indeed, entirely new locations might be preferred or required, and the foundation of choice was bedrock which prevented any undermining by an attacking force. The keep became a staple feature of castles, although they were called a donjon (from the French word meaning 'lord') prior to the 16th century CE. Usually with three or more stories (tower keeps); some were lower and are called hall keeps. The keep was the heart of the medieval castle and the last point of refuge in case of attack or siege. Before they got to the keep, though, attackers had to negotiate a long list of defensive features.

Features of a Medieval Castle

The typical features of a medieval castle were:

- Moat - a perimeter ditch with or without water

- Barbican - a fortification to protect a gate

- Curtain Walls & Towers - the perimeter defensive wall

- Fortified Gatehouse - the main castle entrance

- Keep (aka Donjon or Great Tower) - the largest tower and best stronghold of the castle

- Bailey or Inner Ward (courtyard) - the area within a curtain wall.

Moat

An artificial ditch or moat was dug to surround the entire castle complex and could be filled with water permanently or temporarily during attack in some cases. As creating a moat was a huge undertaking, the presence of natural rises and depressions were important factors in choosing where to build the castle in the first place. The earth or stone excavated while preparing the moat could be used to build up the mound on which the castle would be subsequently built. The moat was made deep enough to impede attackers on horse, foot or equipped with siege towers. The sides were steep and could be riveted with wooden stakes to increase their slipperiness. Stakes might also be placed in the bottom to further impede crossing. If filled with water, only a half-metre depth was required to obstruct the enemy and make them more vulnerable to missiles fired from the walls above.

Barbican

The barbican was a defensive fortification built to protect potential weak spots like a gate. Typically consisting of a short stretch of fortified wall, perhaps forming an echelon form, it allowed the defenders to ward off a direct attack on the wall or gate proper. The barbican could be protected by covering fire from the towers behind it and was sometimes surrounded by its own wall and/or ditch (with accompanying drawbridge or swing bridge) when it was known as a courtyard barbican. A second type was the passageway barbican which was similar to a fortified corridor leading from a gateway outwards. By the mid-13th century CE, barbicans were set more distant from the outer wall, at an angle from a gate and incorporating a 90-degree turn within them (between the entrance and exit bridges) to further impede access to the castle proper.

Curtain Walls & Towers

Walls surrounding the castle proper presented a formidable challenge to attackers. If the foundations were not of rock then they had to be specially prepared to bear the tremendous weight. The most common method was to dig a trench wider than the width of the wall and fill it with rammed stone rubble. Alternatively, oak piles could be driven into the soil to make it more stable. Walls varied in thickness, but an average seems to have been around 2.5 metres. Some were thick enough to contain passageways or murals. Most walls were made of two layers of dressed stones covering a rubble and mortar core. To prevent undermining and make their scaling more difficult both walls and towers could be built on a sloped plinth or a sloped protective curtain (spur) was later added. This slope could also prove useful if projectiles were thrown down on the enemy as they tended to bounce off at unpredictable angles.

With a parapet of crenellations (aka battlements) along the top of the walls, defenders could hide behind the raised parts of the wall (merlons) if necessary and then fire their arrows and crossbows through the lower part (crenels), minimising their exposure to enemy missiles. Crenels might also be protected by hinged wooden shutters which could be lowered when an archer wanted to fire an arrow. Walls had raised internal platforms for defenders to walk along while the internal side of the wall was usually left open in case they were breached and were used to launch further attacks on the inner fortifications.

Towers were added to walls so that the defenders could fire down onto the enemy from multiple angles. Towers evolved from square to D-shaped (1180s CE onwards) and then circular in form, which gave a greater range of fire and eliminated the corner blind spots. Projecting towers gave additional firing possibilities on the enemy as they tried to either scale or undermine the walls. Circular towers were also more structurally stable and better resisted attempts to collapse them either by undermining or picking out stones with tools (corners being a favourite target for sappers). Curved towers had an additional advantage of better deflecting artillery missiles such as heavy stones. If the enemy did manage to climb one section of the wall, then the towers provided a refuge for the defenders from where they could continue to fire their arrows. Archers were able to fire through narrow vertical slits in the stonework which widened on the inside to give a better field of fire. Later, a small horizontal slit was added to further increase the firing range.

As castle design evolved, another, interior circuit of walls became a common feature - the concentric walled castle. Now attackers had to breach two walls, and if they did get through the outer wall, they were extremely vulnerable to fire from the even higher inner wall when crossing the space (ward) between the two lines of defence. Underground tunnels were sometimes excavated to link the two sets of wall and provide an escape route to outside the castle or a sally port which defenders could use to turn the tables and attack the attackers from behind.

From the 15th century CE, when battles were largely fought in the open and castle warfare declined, castles continued to incorporate their traditional defensive features, but these were now largely symbolic and for show only. Imposing towers and crenellations became easily recognisable symbols of power and so were added to large country houses and even to such peaceful institutional buildings as churches and universities.

Fortified Gatehouse

The main gate of a castle was potentially one of its weakest points, and for this reason, gates gained more and more protective features over time. Twin towers were built from the end of the 12th century CE with the gate tucked between them and recessed. The gate itself was protected by a heavy wooden door and a portcullis (or even two) - a metal and wooden grid which could be lowered to block access. There might be a drawbridge, too, which could be raised by chains or, in the quicker version, swung 90 degrees, which meant the enemy had to negotiate a ditch or water-filled moat before they got to the actual doorway. Additional defensive measures included 'murder holes' (machicolations) - holes in projecting battlements above the entrance gate through which missiles or burning liquid could be thrown. Similarly, a water chute allowed the defenders to douse any fires the attackers set against the vulnerable wooden gate door.

Over time, as gatehouses became remarkable strong points, rather than weak points, they were even used as residences, particularly by the castle's constable - he who was in charge of its daily management. Some gatehouses also had dungeons under them and rooms in the upper floors for more honoured prisoners who were being kept for ransom. A chapel, too, might be incorporated into the gatehouse. Larger castles might have a second fortified gate (typically on the opposite side of the circuit wall from the main gate) and one or more very small gates or posterns for single-person access in emergencies.

Keep

The tower keep or donjon was a multi-storied tower building with especially thick walls and a well-defended entrance, which made it the safest place in the castle when under attack. They began to appear in most castles from the early 12th century CE. A keep could be square or rectangular and often had its own small towers or turrets on top; alternatively, some were round and had wooden hoardings around their tops to act as covered firing platforms. Reaching up to a height of 40 metres in some cases (although around 20 metres is more common), these imposing structures were useful indicators of a local lord or sovereign's power besides a hypothetical place of retreat. Expensive to build, towering keeps were steadily being replaced by the 13th century CE with larger round towers in the circuit wall than had been seen previously.

As with any building, the weak spot of a castle keep was the entrance and so this was often accessed by a staircase going directly to the first floor (i.e. above the ground floor). This staircase could be removed if necessary in early castles, and later it was permanent but protected by its own passageway and towers added on to the side of the keep (a forebuilding). The forebuilding was sometimes separated from the keep by a drawbridge, portcullis, and ditch. A huge barred door was the last but still formidable obstacle to attackers who managed to get that far. Even if soldiers got inside the keep, they had to fight their way up the narrow spiral staircases to each succeeding floor, sometimes having to cross an entire floor to reach the next level's staircase.

Roofs were usually of wood and steeply angled. The outer roof surface was protected by shingles, tiles, slates, thatch or lead sheeting. Wood or lead-lined drainage channels, drainpipes, and projecting stone spouts ensured rainwater did not accumulate or damage the stonework of the building.

Typically, the basement of the keep was used for the storage of foodstuffs, arms and equipment. There was usually a deep well to provide drinking water, which could be supplemented by rainfall captured and directed into a cistern. On the ground floor were the kitchens and sometimes stables. The first floor typically contained a great hall for banquets and audiences. This was a room designed to impress and so often had a beautiful wooden beam ceiling or impressive stone vaults, large windows (opening onto the safe interior side of the castle), and a grand fireplace. On this floor too, and perhaps also the floor above as well, were private chambers and usually a chapel. The top floor, sometimes called the solar or 'sun room' because it was safe enough to have bigger windows, was for an uncertain purpose. Heating was provided by fireplaces and portable braziers while windows would have had wooden shutters to keep in the heat when required.

Bailey

In the inner bailey or courtyard, besides the keep, there could be several other buildings such as granaries, workshops (for blacksmiths, carpenters, weavers and potters), a buttery (for wine and beer storage), stables, secondary accommodation, and perhaps a space for hunting dogs and birds if in a bigger castle. These structures were built using stone or more simply with wattle and daub walls and thatch roofs. To ensure a greater self-sufficiency in times of siege, there were gardens and space for poultry and livestock within the protection of the bailey. Larger castles also had a secondary chapel here, too.

Finally, a note on toilets. The latrines of a castle were typically built using a protruding shaft of masonry down a portion of the exterior wall and the waste fell directly into the ditch or moat outside. Toilets had a simple wooden bench with a hole in it, but some were private with their own door while others were merely set in a recess. Triangular urinals were built into some tower walls so that defenders did not have to leave their post for very long. It seems that even such basic human activities were considered by architects to provide the best possible defence of the castle against all comers in all situations.