The Black Death is the 19th-century CE term for the plague epidemic that ravaged Europe between 1347-1352 CE, killing an estimated 30 million people there and many more worldwide as it reached pandemic proportions. The name comes from the black buboes (infected lymph glands) which broke out over a plague victim's body. The cause of the plague was the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which was carried by fleas on rodents, usually rats, but this was not known to the people of the medieval period, as it was only identified in 1894 CE. Prior to that time, the plague was attributed primarily to supernatural causes – the wrath of God, the work of the devil, the alignment of the planets – and, stemming from these, “bad air” or an unbalance of the “humors” of the body which, when in line, kept a person healthy.

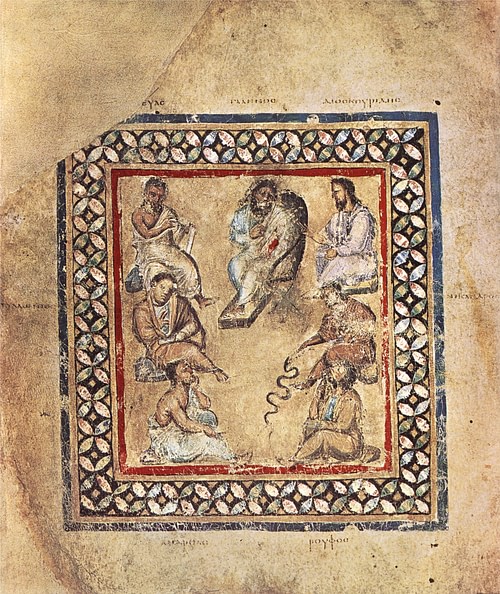

Since no one knew what caused the disease, no cure was possible, but this did not stop people from trying what they could based on the medical knowledge of the time which came primarily from the Greek doctor Hippocrates (l. c. 460 - c. 370 BCE), philosopher Aristotle of Stagira (l. 384-322 BCE), and the Roman physician Galen (l. 130-210 CE) as well as religious belief, folklore, herbalism, and superstition. These cures – most of which were ineffective and some of which were fatal – fall roughly into five categories:

- Animal cures

- Potions, Fumigations, Bloodletting, Pastes

- Flight from Infected Areas and Persecution of Marginalized Communities

- Religious Cures

- Quarantine and Social Distancing

Of these five, only the last – quarantine and what is now known as “social distancing” – had any effect on stopping the spread of plague. Unfortunately, people in 14th-century CE Europe were as reluctant to stay isolated in their homes as people are in the present day during the Covid-19 pandemic. The wealthy bought their way out of quarantine and fled to country estates, spreading the disease further, while others helped with the spread by ignoring quarantine efforts and continuing to participate in religious services and by going about their daily business. By the time the plague ended in Europe, millions were dead and the world the survivors had known would be radically changed.

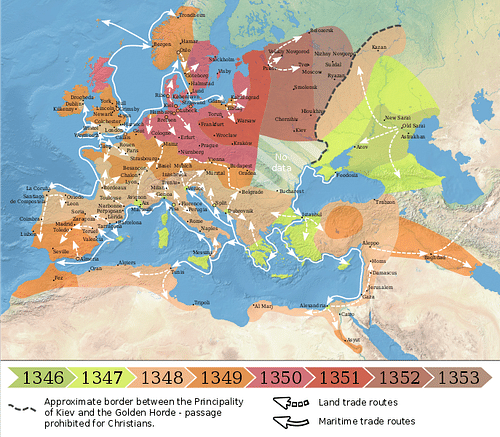

Arrival of the Plague & Spread

The plague had been killing people in the Near East since before 1346 CE, but that year it grew worse and more widespread. In 1343 CE, the Mongols under the Khan Djanibek (r. 1342-1357 CE) responded to a street brawl in the Italian-held Crimean town of Tana in which a Christian Italian merchant killed a Mongol Muslim. Tana was easily taken by Djanibek, but a number of merchants fled to the port city of Caffa (modern-day Feodosia in Crimea) with the Mongol army in pursuit. Caffa was then put to siege but, at the same time, the plague began to spread through the Mongol army between 1344-1345 CE.

The Italian notary Gabriele de Mussi (l. c. 1280 - c. 1356 CE) was either an eyewitness to the siege or received a first-hand account and wrote of it in 1348/1349 CE. He reports how, as the Mongol warriors died and their corpses filled the camp, the people of Caffa rejoiced that God was striking down their enemies. Djanibek, however, ordered the corpses of his dead soldiers catapulted over the city's walls and soon the plague erupted in the city.

It has been suggested by some modern-day scholars that the dead could not have infected the people of Caffa as the disease could not be transmitted by handling corpses but, even if that were true, many of these dead bodies – described as “rotting” – were most likely already in an advanced state of putrefaction and gases and bodily fluids could have infected the city's defenders as they tried to dispose of what de Mussi describes as “mountains of dead” (Wheelis, 2).

A number of the people of Caffa fled the city in four merchant ships which went first to Sicily, then Marseilles and Valencia, spreading the plague at each stop. From these ports, other infected people then spread it elsewhere until people were dying across Europe, Britain, and even in Ireland where ships from Europe had docked for trade.

Medical Knowledge

The physicians of the day had no idea how to cope with the outbreak. Nothing in their experience came anywhere close to the epidemic which killed people, usually, within three days of the onset of symptoms. Scholar Joseph A. Legan notes:

When the Black Death struck Europe in the middle of the 14th century, nobody knew how to prevent or treat the disease. Many believed they could cure it, but none of the bloodletting, concoctions, or prayers were successful. The overall intellectual framework of dealing with illness was flawed. The failure of medieval medicine is largely due to the strict adherence to ancient authorities and the reluctance to change the model of physiology and disease the ancients presented. (1)

None of Galen's works – and little of others' – were available in Latin or Greek to the European doctor who had to rely on Arabic translations which were then translated to Latin along with the Canon of Medicine of the Persian polymath Ibn Sina (also given as Avicenna, l. c. 980-1037 CE) whose brilliant work was often obscured by poor translations. Based on Galen's works, primarily, the basis of medieval medicine was the theory of humors – that the four elements of earth, water, air, and fire are linked to bodily fluids of yellow bile (fire), blood (air), phlegm (water), black bile (earth) and each “humor” was associated with color, a certain taste, a kind of temperament, and a season of the year.

One's health could also be affected by astrological alignment and, of course, by supernatural agencies such as God, Satan, diverse demons, and the “witchcraft” of marginalized peoples such as gypsies, Jews, and others considered “outsiders” who were thought to possess knowledge of the black arts. Scholar George Childs Kohn comments on the causes given for the plague:

The plague was attributed to any and all of the following: corrupted air and water, hot and humid southerly winds, proximity of swamps, lack of purifying sunshine, excrement and other filth, putrid decomposition of dead bodies, excessive indulgence in foods (particularly fruits), God's wrath, punishment for sins, and the conjunction of stars and planets. Religious fanatics asserted that human sins had brought the dreadful pestilence; they roamed from place to place, scourging themselves in public…There was panic everywhere, with men and women knowing no way to stop death except to flee from it. (27-28)

There were many people, however, who did not take to flight but tried to find some means of fighting the disease where they were. Based on the medical knowledge of the time, folk cures which had been passed down for generations, Christian belief, superstition, and prejudice, the people tried any suggestion offered to defeat death.

Animal Cures

One of the most popular cures was the “Vicary Method”, named after the English doctor Thomas Vicary, who first proposed it. A healthy chicken was taken and its back and rear plucked clean; this bare part of the live chicken was then applied to the swollen nodes of the sick person and the chicken strapped in place. When the chicken showed signs of illness, it was thought to be drawing the disease from the person. It was removed, washed, and strapped back on and this continued until the chicken or the patient died.

Another attempt at a cure was to find and kill a snake, chop it into pieces, and rub the various parts over swollen buboes. The snake, synonymous in Europe with Satan, was thought to draw the disease out of the body as evil would be drawn to evil. Pigeons were used in this same way but why the pigeon was chosen is unclear.

An animal much sought after for its curative powers was the unicorn. Drinking a powder made of the ground-up horn of the unicorn mixed in water was thought to be an effective remedy and was also among the most expensive. The unicorn could not easily be caught and had to be lulled into submission by a young virgin maiden. Doctors who managed to procure the powder of a ground “unicorn horn” used it to treat snake bites, fever, convulsions, and serious wounds and so it was thought to work equally well with the plague. There is no evidence that it did, however, any more than the cures involving the chicken or the snake.

Potions, Fumigations, Bloodletting, & Pastes

The unicorn potion was not the only – or most expensive – cure offered to the nobility or wealthy merchant class. Another remedy was eating or drinking a small quantity of crushed emeralds. The physician would grind the emeralds with a mortar and pestle and then administer it to the patient as a fine powder mixed with either food or water. Those who could not afford to consume emeralds drank arsenic or mercury which killed them faster than the plague.

One of the best-known potions was Four Thieves Vinegar which was a combination of cider, vinegar, or wine with spices such as sage, clove, rosemary, and wormwood (among others) thought to be a potent protection against the plague. It allegedly was created and used by four thieves who were able to rob the homes of the dying and graves of the dead because the drink made them immune to the plague. Four Thieves Vinegar is still made and used today in the practice of homeopathic medicine as an antibacterial agent; though no one in the modern-day claims it can cure the plague.

The most popular potion among the wealthy was known as theriac. Legan notes, “it was very difficult to prepare; recipes would often contain up to eighty ingredients, and often, significant amounts of opium” (35). The ingredients were ground into a paste which was mixed with syrup and consumed as needed. Precisely what the ingredients were and why it worked, however, is unclear. Theriac in its liquid form was often referred to as treacle but it seems it could also be applied as a paste.

Aside from potions, clearing the air was considered another effective remedy. Since the plague was thought to spread by “bad air”, homes were fumigated with incense or simply smoke from burning thatch. People carried bouquets of flowers which they held to their faces, not only to ward off the stench of decomposing bodies, but because it was thought this would fumigate one's lungs. It was this practice which gave rise to the children's rhyme “ring around the rosy/a pocketful of posie/ashes, ashes, we all fall down” in reference to the practice of filling one's pockets with flowers or sweet-smelling substances to keep one safely fumigated at all times. As the rhyme suggests, this was as ineffective as any of the other cures.

It was also thought that one could fumigate one's self by sitting close to a very hot fire which would draw the disease out by heavy sweating. Another technique was to sit by an open sewer as the “bad air” which was causing one's sickness would gravitate to the “bad air” of the sewage of the stream, pond, or pit used for dumping human waste.

Bloodletting was a popular remedy for all kinds of illnesses and was well established by the medieval period. It was thought that, by drawing out “bad blood” which caused illness, health would be restored by the “good blood” that remained. The preferred method was “leeching” in which a number of leeches would be placed on the patient's body to suck out the “bad blood” but leech-collectors were a highly-paid profession and not everyone could afford this treatment. For the less affluent, a small incision was made in the skin with a knife and the “bad blood” collected in a cup and disposed of. Another method along these same lines was “cupping” in which a cup was heated and applied upside down to a patient's skin, especially the buboes, to draw the sickness into it.

Aside from theriac paste, doctors also prescribed a cream made of various roots, herbs, and flowers which was applied to the buboes one they were lanced. Human waste was also turned into a paste for the same purpose which no doubt led to greater infection. Since it was believed that clean urine had medicinal properties, people would bathe in it or drink it, and urine collectors were paid well by doctors for a clean product.

Flight from Infected Areas & Persecution

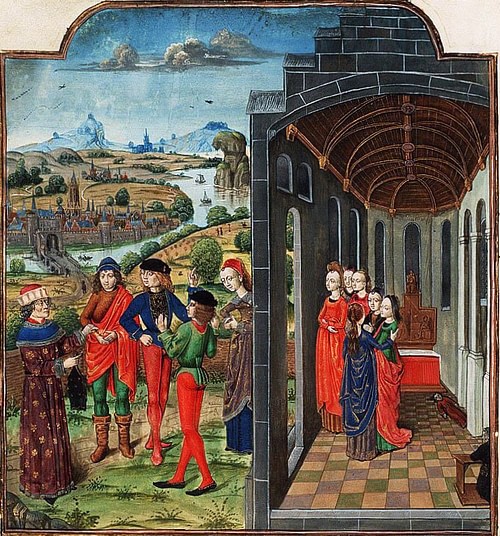

Those not wishing to bathe in urine, be smeared with feces, or try the other cures, left the affected region or city, but this option was usually only available to the wealthy. The Italian poet and writer Giovanni Boccaccio (l. 1313-1375 CE) describes the flight of ten affluent young people from Florence to a countryside villa during the plague in his masterpiece The Decameron (written 1349-1353 CE) where the characters tell each other stories to pass the time while the plague rages on in the city.

These types of people, and many others of all social classes, also tried curing the plague by striking at what they considered its source: marginalized groups who were considered outsiders. Kohn writes:

In places, the plague was blamed on cripples, nobles, and Jews, who were accused of poisoning the public wells and were either driven away or killed by fire or torture. (28)

In addition to those groups mentioned by Kohn, many others were also singled out who were in any way considered different and did not conform to the standards of the majority.

Religious Cures

That standard, for the most part, was set by the medieval Church which informed the worldview of the majority of the population of Europe at the time. Religious cures were the most common and, besides the public flagellation mentioned above, took the form of purchasing religious amulets and charms, prayer, fasting, attending mass, persecuting those thought responsible, and participating in religious processions.

The pope eventually put a stop to the public flagellations as ineffective and upsetting to the populace, but by that time, participants had spread the plague to every town or city they had visited. Processions, in which participants marched and prayed for mercy usually from a central point in town to the church or a shrine, did the same on a smaller scale as did public gatherings to hear mass.

Quarantine & Social Distancing

The only effective means of stopping the spread of the plague – though not curing it – was separating the sick from the well through quarantine. The port city of Ragusa (modern-day Dubrovnik, Croatia), at that time under the control of Venice, was the first to initiate this practice through a 30-day isolation period imposed on arriving ships. Ragusa's population had been heavily depleted by the plague in 1348 CE, and they recognized that the disease was infectious and could be transmitted by people. Ragusa's policy was effective and was adopted by other cities and extended to 40 days under the law of quarantino (40 days) which gives English its word quarantine.

Although quarantine and social distancing seem to have had a positive effect, governments were slow to implement the policies and people reluctant to follow them. Kohn writes:

The segregation of the sick was ordered in many cities but in some the quarantine practice and stations were put into effect too late, such as in Venice and Genoa, where half the people succumbed. (28)

Milan, on the other hand, imposed stricter measures and enforcement and had greater success in controlling the spread of the disease. The Milanese authorities tolerated no dissension among the citizenry in obeying the laws of quarantine, at one point completely sealing the infected occupants of three houses in their homes where, presumably, they died. In 1350 CE, they built a structure outside the city walls – the pesthouse – where plague victims were housed and caregivers could tend them. The plague doctors are famously depicted in cloaks and hats with beaked masks which were thought to protect the wearer by distancing the physician's face – especially the nose and mouth – from the infected patient.

Conclusion

As the plague raged on, other measures were attempted such as washing money with vinegar, fumigating letters and documents with incense, and encouraging people to think positive thoughts as it seemed to become clear that a patient's general attitude greatly affected the chances of survival. None of these proved as effective as separating the infected from the healthy but people still broke quarantine and continued the spread of the disease.

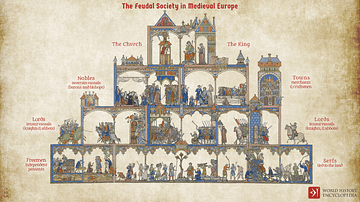

By the time the plague had run its course, over 30 million people – 30-50% of the population of Europe – were dead. The loss of population transformed European society, ending the feudal system, establishing wages for former serfs, and elevating women's status in that many mothers, wives, and daughters survived the males of the family and assumed their roles.

Kohn notes that, “to many historians, the Black Death marked the end of the Middle Ages and the start of the modern age” (28). This conclusion is sound in that, afterwards, people's disillusionment with the religious, political, and medical paradigms of the past inspired them to seek alternatives, and these would eventually find full expression in the Renaissance which lay the foundation for the world of the modern era.

![Ancient Medicine by Nutton, Vivian [Routledge,2012] (Paperback) 2nd edition [Paperback]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/215+XqWEjeL._SL160_.jpg)