Medieval Trades were essential to the daily welfare of the community and those who learned a skill through apprenticeship could make a higher and more regular income than farmers or soldiers. Professionals like millers, blacksmiths, masons, bakers and weavers grouped together by trade to form guilds to protect their rights, guarantee prices, maintain industry standards and keep out unlicensed competition.

As towns grew into cities from the 11th century so trades diversified and medieval shopping streets began to boast all manner of skilled workers and their goods on sale, from saddlers to silversmiths and tanners to tailors. Naturally, trades and trading practices varied over time and place throughout the Middle Ages and so what follows is a general overview of some of the common and interesting features of trades in medieval Europe.

Apprenticeship

Many children learnt the trade of their parents by informal observation and helping out with small tasks but there were also full apprenticeships, paid for by parents, where young people lived with a skilled worker or master and learned their craft. Very often a master who took on an apprentice also took on the role of parent, providing all their needs and moral guidance while in turn the apprentice was expected to be obedient to their master in all matters. An apprentice was not usually paid but did receive their food, lodgings and clothing. Boys and girls typically became apprentices in their early teens but sometimes they were as young as seven years old when they started out on the long road to learn a specific trade. There were many cases of apprentices running away and rules were established that the master and the apprentice's father had to spend one day each looking for the missing youth. There were time limits of one year, after which a master need not take the escapee back under apprenticeship.

The length of the apprenticeship depended on the trade and the master (the benefit of free labour was a temptation to extend the training for as long as possible) but around seven years seems to have been the average. A cook's apprentice might only need two years training while at the other end of the spectrum a metalworker like a goldsmith might have to learn their trade for ten years before they could set themselves up with their own business. An apprentice usually qualified by producing a 'masterpiece' which showed off his acquired skills. Earning the title of master cost money besides skill, though, and a qualified apprentice who could not afford their own place of business was known as a journeyman as they usually travelled around and found work with a master with premises wherever they could.

Medieval Guilds

Once their own business was up and running, from the 12th century master tradesmen became members of guilds. These organisations, managed by a core group of seasoned professionals known as guildmasters, sought to protect the working conditions of their members, ensure their products were to a high standard and outside competition was minimised. Regular inspections ensured (at least to some degree) that goods were exactly what they were advertised as, that regulation measurements and weights were adhered to, that prices were correct and that members did not unfairly compete with each other for clients. By imposing regulations on apprenticeship, guilds could also regulate the labour supply and ensure there were not too many masters at any one time and the prices of both labour and goods did not crash.

Women in the Trades

While there were very few guilds specifically for or managed by women, and although most apprentices were male and so too their masters, there was a significant minority of women involved in some trades. Widows, especially, were prominent in the trades as they could, if they were without a close male relative and they remained single, run their deceased husband's business. There were some restrictions, though; for example, they were not able to train an apprentice themselves. Some trades such as the poulterers of Paris did permit any woman with means to own businesses, while many trades such as silk production and veil makers were dominated by women workers. There are records (notably tax assessments), then, of all manner of trades being managed by women from lacemakers to butchers.

The Miller

Each castle or manor had its own mill to serve the needs of its surrounding estate, not only for the grain from the lord's lands but also that of the serfs who were usually obliged to grind their grain at the lord's mill. Mills could be powered by wind, water, horses or people. One essential item to set up business was a good quality millstone that did not wear smooth quickly but, unfortunately, this was a pricey commodity. The Rhineland gained a great reputation for producing the best millstones and one of those could cost 40 shillings or the equivalent of ten horses in England. With such a heavy investment and because a castle or manor did not need to use its mill very often (even if ground grains did not keep very long), the mill was often rented out to a miller who could then make whatever profit he could from it.

The miller enjoyed a high social status in the community because he was essential to it, had a steady income and it was not an unpleasant job to do. Still, because a miller had to make money in order to pay for the mill's rent, they were sometimes viewed with suspicion by other villagers who worried that they never quite got back the quantity of flour their grain had warranted. As one medieval riddle went:

What is the boldest thing in the world?

A miller's shirt, for it clasps a thief by the throat daily.

(Gies, 155)

The Blacksmith

In the Middle Ages, the cheapest materials were wood and clay but some items required metal, usually iron, which was much more expensive. Thus the blacksmith was as essential as the miller to any medieval community. Many agricultural tools needed iron parts, if only for their cutting edges, and so blacksmiths were kept busy producing new tools and repairing old ones. Cooking pots and horseshoes were other sought-after products from the blacksmith's near-magical ability with forge, hammer and anvil. However, such was the medieval necessity of making things last as long as possible that a village blacksmith might not be so busy that he could earn a living, and he also needed an impressive but costly range of tools and equipment himself in order to fulfill orders. Consequently, blacksmiths usually inherited the business from their fathers and many also farmed some land to make ends meet. A blacksmith at a manor or castle was better off as he might receive charcoal made from the trees of the lord's forest for free and have the benefit of a couple of the lord's serfs working his small strip of farmland while he was busy with his hammer and tongs.

The Baker

With bread forming such an important part of the medieval diet, especially for the lower classes, the bakers were another ever-present trader but they were, for the same reason, one of the most regulated. Regular inspections, at least in towns, ensured bakers were serving the right quality, size and weight of loaves. For this reason, bread was typically stamped with an identification mark of just who had baked it. Despite these precautions, it was not unknown for bakers to supplement the flour content of bread with something a little cheaper like sand. Those who tried to swindle their customers and were caught often found themselves chained to a pillory with the offending bread tied around their necks. In order for fresh bread to be available in the mornings, bakers were one of the few tradesmen permitted to work at night.

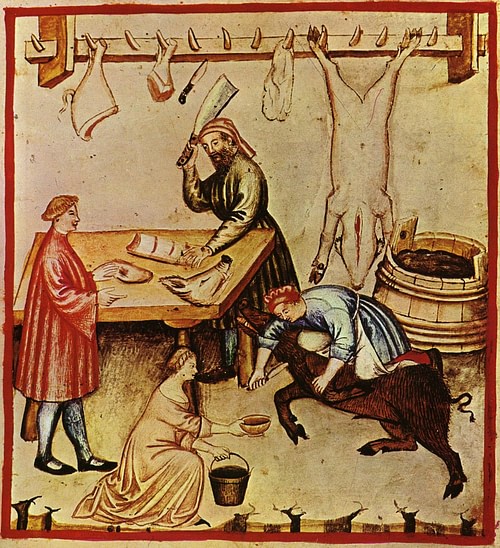

The Butcher

The butcher prepared choice cuts of pork, mutton, and beef as well as poultry and game. Selling an expensive commodity and occupying the dirtiest and smelliest part of the town, butchers were right down there with the fish merchants in the low popularity stakes amongst urban shoppers. In addition, as with the bakers, many people were suspicious of just what a butcher put in his sausages to save money. As one joke went:

A man asked the sausage butcher for a discount because he had been a faithful customer for seven years. “Seven years!” exclaimed the butcher. “And you're still alive!”

(Gies, 49)

To keep consumer confidence high, there were additional rules imposed by the butchers' guild which prohibited the sale of meat from such animals as cats, dogs, and horses, as well as outlawing the mixture of tallow with lard.

The Weaver

Many peasant women spun thread in the home and then sold it on to a weaver, who was usually male. Although some women would have continued to weave on an upright loom, by the High Middle Ages weaving was typically done on a larger scale by a skilled weaver using a horizontal loom which was beyond the means of a peasant. England and Wales enjoyed a high reputation for their wool in medieval times while Flanders became a major centre of wool cloth production. Wool was washed to remove grease, then dried, beaten, combed and carded. The wool was then spun and worked on the loom to make a rough cloth which was next fulled (soaked, shrunk and then usually dyed), sometimes using a water-powered mill or trampled underfoot. The cloth was then sheared and brushed, perhaps many times, in order to produce a very fine, smooth cloth.

Builders

One thing everyone needed was a roof over their heads. As societies became more prosperous, towns grew in size and construction techniques improved from the 13th century, so many people looked for better and more substantial homes to live in. Prosperous peasants looked to improve on their traditional mud and timber cottages while lords were looking to impress with manor houses that might look like the castle most of them could not afford. Consequently, there developed many specialised trades for each facet of any building's construction such as masons, tilers, carpenters, thatchers, glassmakers and plasterers. Carpenters, especially, were involved in the subsequent upkeep of houses and other structures such as barns, granaries, churches and bridges.

At the top of the building profession were the master builder and master mason, both of whom needed to be skilled in mathematics and geometry to produce their scale models and parchment plans upon which lesser workers would depend in order to make the real-life pieces of a building fit together properly. As they rarely lifted a finger themselves, they also needed to be good managers of the large team of skilled workers under their command on specific projects, especially the big ones like building a castle or church.

City Traders

Larger towns and cities, of course, had especially numerous and diverse tradespeople. There were tailors, drapers, dyers, saddlers, furriers, chandlers, tanners, armourers, sword makers, parchment makers, basket-weavers, goldsmiths, silversmiths and, by far the biggest industry sector, all manner of food sellers. Many of these trades might be grouped together in parts of a city so that guilds could better regulate their members or to attract visitors such as by the city gates or because a particular area had a tradition for one trade (like Notre-Dame in Paris had for books, which it still has today).

Medical Practitioners

Medieval doctors, at least in the later Middle Ages, learnt their expertise at a university and enjoyed a high status but their practical role in society was limited to diagnosis and prescription. A patient was actually treated by a surgeon and given medicine which was prepared by an apothecary, both of whom were regarded as tradesmen because they had learnt their skills via the system of apprenticeship. As a surgeon could be expensive, many of the poorer class took their minor physical problems to a much cheaper option; the local barber. When not cutting hair and trimming moustaches, a barber performed minor surgeries and also pulled teeth. The poor might also seek the skills of a peddler of folk medicine who dispensed advise and lotions based on traditional and natural remedies which, despite their dubious origins, must have worked to some degree in order for them to keep practising throughout the Middle Ages.