Ancient Mesopotamian Government was based on the understanding that human beings were created to help and serve the gods. The high priest, king, assembly of elders, governors, and any other officials were recognized as stewards chosen by the gods to care for the people in the same way a father was expected to care for his family.

The family in ancient Mesopotamia, in fact, was the model for Mesopotamian government as the king and priest were understood as the 'head of a household' who were responsible for the 'extended family' of the people of the city-state, kingdom, or empire. In the Uruk Period (4100-2900 BCE), the high priest was in charge of both religious and civic affairs, but this changed in the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE) when kingship was established.

Kingship developed in Sumer from the concept of the lugal ("strong man"), the head of a clan, who had been elevated to that position through effective leadership and military skills. The Sumerian King List (c. 2100 BCE) gives the first monarch "after the Flood" as Enmebaragesi (r. c. 2700 BCE) of Kish, whose historicity is attested by archaeological evidence, but it also gives the names of legendary kings who ruled from Eridu before the Great Flood (c. 2900 BCE).

With the rise of a king, a division of responsibility was established between the throne and the temple; the king dealt with the administration of civic affairs, and the high priest or priestess with the concerns of the temple. Both king and clergy, however, were understood as serving the will of the primary gods of the state, and so were the officials under them, eventually including:

- Prime Minister

- Judiciary Assembly

- Assembly of Elders

- Governors

- Temple Priests

- General of the Army

- Palace Chamberlain

- Palace Chief-of-Staff

- Royal Cup Bearer

- Tax Collector

- Palace, Temple, and Administrative Scribes

- Support Staff for All of the Above

The details of the government in operation changed with the rise and fall of successive powers – Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Kassite, Hittite, Assyrian, and so on – but the original paradigm of government as established by and serving the will of the gods remained the same. As with many of the innovations, inventions, and 'firsts' of ancient Mesopotamia, the concept of government began in Sumer.

Sumerian Government

The Sumerian King List begins with the line, "After the kingship descended from heaven, the kingship was in Eridu." Eridu was regarded by the Sumerians as the oldest city in the world, established by the god of wisdom Enki, and the site from which order was established. After the Great Flood, thought by modern-day scholars to be a local event involving the rivers around the city of Shuruppak, kingship moved to Kish. Precisely when kingship was established, however, is impossible to determine, as scholar Stephen Bertman notes:

There is no doubt that Mesopotamia was eventually and for most of its history governed by rulers we might call "kings." Indeed, we even know their names and can catalogue their careers. But exactly when kingship first came into being, under what circumstances it arose, and precisely what its nature was remain matters of scholarly contention. Theories abound, but facts are few. (63)

According to some scholars, kingship was established during the Uruk Period by c. 3600 BCE at which time the division of responsibility between throne and temple was recognized. This was the model of government by the time of the period of Early Dynastic I (2900-2800 BCE). The cities that developed throughout Sumer during the Uruk Period had by this time expanded, and it is thought it was no longer possible for one man to govern effectively managing both civic and religious duties.

The structure of the government was based on that of a household where the father was the head and all others below him. The king shared the role of 'head of the household' with the high priest, and then came the queen, the counselors, the lesser priests, the military command, and so on. The stability of the household model of government, in which the king was to care for his people as a father his children, provided the stability that enabled the development of Sumerian culture, but at the same time, the lack of unity among the Sumerian states, vying for food and water resources as well as trade routes, encouraged ongoing military conflicts.

The first war in recorded history comes from the period of Early Dynastic II (2800-2600 BCE) when Enmebaragesi of Kish defeated Elam in 2700 BCE. This is simply the first conflict recorded, however, and there were no doubt many earlier as the city-states established their territories. Trade in ancient Mesopotamia contributed to the wars between the city-states as each tried to outdo the others in acquiring long-distance and local markets and maintaining the fastest routes between production centers, merchants, and customers.

By Early Dynastic III (2600-2334 BCE), Enmebaragesi had already founded his empire in Sumer, and other kings – such as Gilgamesh of Uruk – had expanded his city's reach. The only queen on the Sumerian King List – Kubaba of Kish – built on the accomplishments of Enmebaragesi, but each Sumerian city-state not under direct control of another still had its own king, high priest, administration, and military.

Akkadian Empire

This changed after the rise of Sargon of Akkad (Sargon the Great, r. 2334-2279 BCE) of the Akkadian Empire (2334-2218 BCE), the first multinational empire in the world. Sargon retained the Sumerian model of division of responsibility between king and priest, but only in his capital city of Akkad. After conquering the Sumerian city-states, he created the position of Citizen of Akkad, trusted officials who were sent from Akkad as governors, administrators, and high priests or priestesses – who were not on equal footing with him – to over 65 different cities. Among these was his daughter, Enheduanna (l. 2285-2250 BCE), high priestess at the city of Ur, and the first author in history known by name.

Sargon attributed his military success to the goddess Inanna and so retained the Sumerian concept of government as mandated by the gods with a king and his court as stewards. According to this model, it was not Sargon who ruled by his own will and understanding, but the gods; Sargon was merely their instrument through whom they maintained order. By encouraging this understanding throughout his empire, Sargon established the largest sovereign state in the world up to that time. Scholar Thorkild Jacobsen comments:

The only truly sovereign state, independent of all external control, is the state which the universe itself constitutes, the state governed by the assembly of the gods. This state, moreover, is the state which dominates the territory of Mesopotamia; the gods own the land, the big estates, in the country. Lastly, since man was created especially for the benefit of the gods, his purpose is to serve the gods. Therefore, no human institution can have its primary aim in the welfare of its own human members; it must seek primarily the welfare of the gods. (Bertman, 65)

By presenting himself as a representative of the gods, Sargon was able to maintain control over his empire. Even so, he and his successors were forced to put down multiple rebellions by city-states who disagreed with his 'stewardship' and, when the Akkadian Empire finally fell to the Gutians, it was seen by many as a sign the gods had withdrawn their favor.

Ur III Dynasty & Babylon

The city-states did not object to the model of Akkadian government – it was the same they had known from the beginning – but to the policies of the Akkadian kings, the implementation of that model. Sargon and his successors treated each city-state in their empire as an occupied territory governed by officials loyal to and concerned with the affairs of the Akkadian state, not necessarily the people of the city they presided over. Sargon's grandson, Naram-Sin (r. 2261-2224 BCE), led more military expeditions than his predecessors and was the first Mesopotamian king to declare himself a god, making himself an equal of the gods worshipped in the individual cities. Scholar Paul Kriwaczek comments:

For a patrimonial state to be stable over time, it is best ruled with consent, at least with consent from the largest minority, if not from the majority. Instinctive obedience must be the norm, otherwise too much effort needs to be put into suppressing disaffection for the regime's wider aims to be achievable. (149)

The Akkadian kings needed to keep suppressing disaffection throughout the entire duration of the empire, but after the Gutians took control of the region, another king emerged who understood the value of government by consent of the governed: Ur-Nammu (r. 2047-2030 BCE) founder of the Third Dynasty of Ur in Sumer (the so-called Ur III Period, 2047-1750 BCE). Ur-Nammu publicly associated himself with the Akkadian kings (who, after the difficulties of the Gutian occupation, had become folk heroes), but as a better and kinder monarch, a true father figure who cared for his people.

The Akkadian kings had built roads, improved trade, restored cities and temples, established and maintained order, and the kings of the Ur III Period did the same, but with a much lighter hand. Instead of mandating behavior, Ur-Nammu issued laws – as a father would lay down rules for his household – the Code of Ur-Nammu – with fines for most infractions. He refurbished the cities and rebuilt the temples damaged or destroyed by the Gutians, including Ur where he commissioned the great ziggurat in the temple complex, dedicated to the moon god Nanna, patron of the city.

Ur-Nammu's son and successor, Shulgi of Ur (r. 2029-1982 BCE), encouraged literacy, improved roads, instituted inns, and roadside gardens, and although he was the second king in Mesopotamian history to deify himself, his inscriptions (though challenged) claim this was met with approval by the people.

The Ur III model was adopted by the Babylonian king Hammurabi (r. 1792-1750 BCE), who was known by the epithet bani matim ("Builder of the Land") for his many improvements to the infrastructure. Like Ur-Nammu, Hammurabi also issued laws – the Code of Hammurabi – which followed the same model as having been issued by the gods, in this case, the deities Anu and Bel through the champion-god Marduk and god of justice (and the sun) Shamash.

Hammurabi's Code not only legislated behavior but also defined one's social status and how one's position in the social hierarchy reflected treatment before the law, as Bertman explains:

According to the code, there were three types of persons in society: the awilum, or patrician (a member of one of the landholding families), the mushkenum, or plebeian (a citizen who was free but did not possess land), and the wardum, or slave (a member of society who neither owned land nor was free). Significantly, the most privileged were also held to the highest standard of responsibility under the law, while those who were less privileged were penalized less for breaking it, unless it happened that their offense was committed against a member of a higher class. (62)

Hammurabi's Code was based on the concept of retributive justice in which the severity of punishment corresponds directly to the seriousness of the crime and conviction is based upon evidence of wrongdoing. Even so, this 'evidence' was brought through the much older method of the 'ordeal' which usually took the form of the accused being thrown into a river or another body of water, and if they survived, they were judged innocent as the gods had spared them.

Assyrian Empire

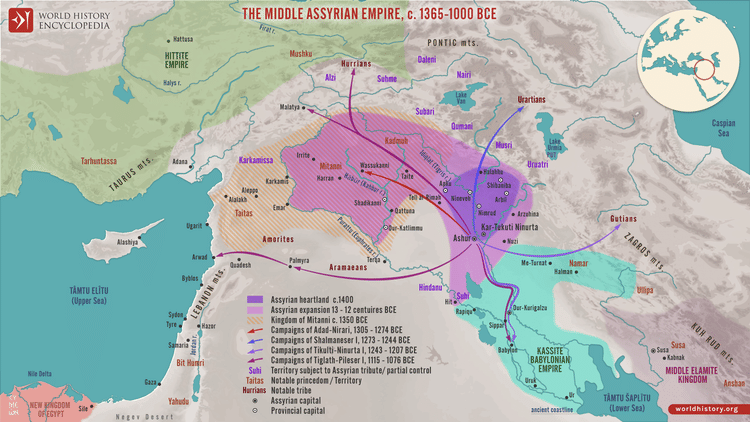

The gods also informed the government and legal system of the Assyrian Empire, which worshipped the god Ashur (also given as Assur) as the supreme deity just as the Babylonians had Marduk. From a minor god of the city of Ashur c. 1900 BCE, Ashur came to be regarded as one of the most important by the reign of Adad Nirari I (1307-1275 BCE). The Assyrian government represented the will of Ashur, and it was he who was believed to march with the armies and give them victory in their campaigns of conquest.

The symbols of kingship during the Assyrian Period were the same as they had always been – the crown, scepter, and throne – and the responsibilities of government were the same as well, but the Assyrian kings were much closer to the Akkadians and their policies of suppressing discontent than the Sumerian or Babylonian method of legal codes. Like all the kings before them, the Assyrian monarchs relied on taxes to fund the government, and it was one's sacred duty to pay what was owed as one was not thought to be giving to the government officials but to the gods – and in this case, Ashur – who empowered those officials and had placed them in positions of authority. Bertman comments:

Nominally, all the lands and waters of a Mesopotamian city-state belonged to its gods and were managed by their surrogates, the rulers and priests. Individuals who used the lands and waters and derived economic benefit from them were, in turn, subject to taxation. Because coinage had not yet been invented, taxes were paid in the form of goods and services. Normally the goods represented a share of what had been produced (such as grain, dates, fish, wool, or livestock) or a percentage of its worth in silver. Services could be rendered through military service or by laboring on communal projects (the excavation and maintenance of irrigation canals; the harvesting of crops grown on communal land; or the construction of temples and palaces). Merchants were also subject to special taxes when they shipped or received goods, or when they passed through cities along trade routes or crossed rivers. (67-68)

During the Assyrian Period, as with earlier eras, revenue also came through conquest. When Sargon II (r. 722-705 BCE) conquered Urartu in 714 BCE, he filled the government's treasury with the spoils. There is no evidence, however, of any tax relief for the people and the tax collector was as feared and hated during the Assyrian period as in any of the earlier eras. Under Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 BCE), the government not only collected taxes but also books for the library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh, creating the largest and most systematic collection of written works taken from every region of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

Conclusion

After the Neo-Assyrian Empire fell in 612 BCE, the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626-539 BCE) controlled the region and followed the same model of government established centuries before by the Sumerians. Nabopolassar (r. 626-605 BCE) founded and maintained the government of his empire on the same concept of the king as steward as earlier kings had done, and this policy was followed by his successor Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605/604-562 BCE).

The empire fell under the reign of Nabonidus (r. 556-539 BCE) to Cyrus II (the Great, r. c. 550-530 BCE) of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) who instituted a centralized government with decentralization of administration which was carried out by satraps (governors) of the various provinces. In many ways, the ancient Persian government was the same model as the Assyrians and Akkadians had observed but with significant differences.

The high priest was no longer a co-ruler with the king by the time of the Achaemenid Empire, and administration of civil affairs and finances in each province was solely the responsibility of the satrap; military matters were dealt with by a general who commanded that province's troops. Rebellion by a satrap was thereby neutralized before it could be mounted as the Persian governor of any region had no access to the troops while the general was prevented from accessing the funds he would require to mount his own insurrection.

This model of government was adopted by the succeeding Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE), Parthian Empire (247 BCE-224 CE), and Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE) and is considered the most effective model of the ancient world. By the time of the Sassanian Empire, the old gods of Sumer, Akkad, Babylonia, and Assyria had been displaced by the one god, Ahura Mazda, of Zoroastrianism, but the model still held of the monarch as steward of the lands rightfully belonging to the divine whose primary responsibility was the care of the people.