Ancient Mesopotamian Warfare progressed from companies of a city's militia in Sumer to the professional standing armies of Akkad, Babylon, Assyria, and Persia and from conflicts over land or water rights to wars of conquest and political supremacy. Developments in weaponry, training, and tactics made the armies of Mesopotamia among the most effective in the ancient world.

The first war in recorded history was between Sumer and Elam c. 2700 BCE, though there were no doubt military conflicts left unrecorded before that date. Afterwards, armed conflict is regularly attested through inscriptions, artwork, and archaeological evidence from the time of the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE) through that of the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE). Scholar Stephen Bertman comments:

The geography of Mesopotamia encouraged war. Mesopotamia is geographically defined by its mountains in the north, its alluvial plains in the south, and the rivers that connect them. The existence of not one but two major river valleys promoted the development of multiple settlements; the fertility of the valleys generated wealth; wealth, in turn, incited competition and greed; and the flatness of the plains made individual communities vulnerable to attack. The net effect in the south was a coalescence of power through imperialism: Akkad absorbed Sumer, and Babylon absorbed both. Eventually, mountainous Assyria in the north – which had always been topographically separate from the south and, because of its terrain, more defensible – marched upon the south and conquered it, and then went on to build an even wider empire. To life in Mesopotamia, therefore, warfare was a natural condition. (262)

Bertman's claim is supported by the inscriptions of kings, Mesopotamian literature, archaeological evidence, and Mesopotamian art (including the Royal Standard of Ur) and architecture (especially in the form of defensive city walls), all strongly suggesting a state of ongoing warfare for over 3,000 years broken by periods of peace briefly maintained by victors.

Sumerian Warfare

Among the many 'firsts' of ancient Sumer, as noted, is the first recorded war as well as the first monument to a military victory, the Stele of the Vultures, dated to the period of Early Dynastic III (2600-2334 BCE). The stele commemorates the victory of Eannatum, king of Lagash, over Ush, king of Umma. The monument, which takes its name from the depiction of vultures flying over the bodies of the fallen, shows Eannatum leading his victorious army over the corpses of the men of Umma on one side while, on the obverse, the war god Ninurta captures Eannatum's enemies in a net and the Mother Goddess Ninhursag is shown giving her blessings.

The two sides of the Stele of the Vultures (which today exists only in fragments in the Louvre) illustrate how wars were fought in ancient Sumer as well as the rationale given: the war was not between two kings but between their gods. In this case, Ninurta, patron god of Lagash, was warring with Shara, patron god of Umma; Eannatum and Ush were merely the instruments they worked through. Humans were thought to have been created to serve the gods and kings to be those gods' representatives. Accordingly, warfare was justified as the will of the gods to maintain the established order.

The war of Lagash and Umma was over a piece of irrigated land that lay between the two cities which had been marked by a boundary stone. Ush had removed that stone and entered the territory of Lagash. Open land for grazing livestock in Mesopotamia was vital to a city's survival as the fields directly surrounding a settlement were given over to agriculture. Farther fields were necessary for livestock, and there were no doubt many more unrecorded conflicts over these spaces as well as over water supplies.

By removing the boundary stone, it would have been thought, Ush transgressed against the will of the gods, who had created order out of chaos, as well as failed in his responsibility to help maintain that order. Eannatum, responding according to the will of Ninurta, claims in the stele that he triumphed in the name of justice, of the restoration of order, and Ush is depicted as promising to never threaten the stability of the region again.

Whether a king actually believed this is unknown. Eannatum's war against Umma was only one of many as he steadily conquered Sumer to create an empire and, although he may have believed he was doing so to maintain order, it seems more likely it was for control of centers of production and trade routes that ran through the region. The king Lugalzagesi of Umma (r. c. 2358-2334 BCE) would later follow the same course and, probably, for the same reasons.

Each of the city-states Eannatum or Lugalzagesi marched against had its own militia mobilized as needed. The soldiers carried bronze or iron spears for thrusting, javelins for hurling, axes, daggers, slings, and simple bows. Chariots, pulled by donkeys, were four-wheeled heavy vehicles, which moved slowly and seem to have served as mobile armories as they are usually depicted with a supply of spears or javelins. The armor and helmets of the troops were initially leather but, by c. 2500 BCE, were copper and bronze. The Sumerians also have the honor of the 'first helmet' – the so-called Golden Wig (Helmet of Meskalamdug) – dated to 2500 BCE.

The Army of Akkad

Militia forces could number from a few hundred to 6,000 or more, depending on the size and wealth of a city. Scholar Paul Kriwaczek describes the troops as they would have been formed for battle:

We should see a Sumerian military unit as consisting of a central shock-force, a tightly packed phalanx of several hundred, perhaps thousand, spearmen. To control them, drill them, and keep them in proper formation would have required many skilled and loud-voiced NCOs; to keep them in step, marching steadily forward or maneuvering in close order, they would have needed music, perhaps a corps of drummers. And behind this central strike-force another thousand or so slingers, the equivalent of today's riflemen, fusiliers, or even gunners, would have been drawn up in loose formation, buzzing around like angry wasps, sending lethal showers of both small and large projectiles into the heart of the enemy's formations, supported by the ass-drawn battle chariots carrying supplies of missiles. (93)

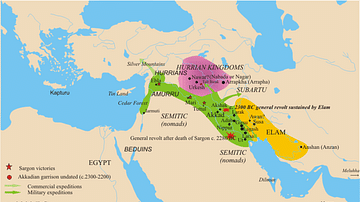

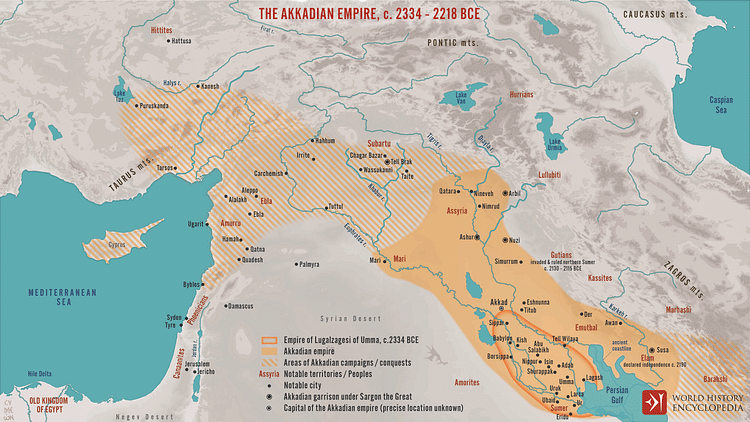

This would have been the kind of army Eannatum led against the other city-states, and it would form the basic model improved upon by Sargon of Akkad (Sargon the Great, r. 2334-2279 BCE) who conquered Sumer in 2334 BCE and established the Akkadian Empire (2334-2218 BCE), the first multinational empire in the world. Sargon began his conquest with troops loyal to him and then conscripted others from the cities he vanquished. Once he had consolidated power and Sumer was subdued, he established a professionally trained, standing army and expanded his empire up through the region of modern-day Syria, down through Lebanon, and over to the Zagros Mountains and the region of modern-day Iran.

To maintain order throughout his empire, he installed trusted officials and family members as governors, high priests and priestesses, and administrators in all his cities, people who were loyal to him, not necessarily to the people of a given city, and garrisoned each with his troops, having disbanded the militias of the cities. Kriwaczek writes:

This must have been a highly militarized society, with armed warriors often seen patrolling the streets, particularly in provincial cities, on whose loyalty the center could not always depend. Sargon wrote that every day 5,400 men, perhaps the nucleus of a standing army, took their meal before him in Akkad. (125)

Having replaced the local militias with a professional army, Sargon then improved upon their formation and reach. He had the troops trained to fight in a tightly formed, six-man-deep phalanx with the front line protected from enemy fire (from slings and bows) by long, rectangular shields. As the phalanx marched toward the opposing army to break their front line, slingers and archers behind it would open fire on the enemy with the archers using the most significant improvement in warfare: the composite bow.

The composite bow, made of layers of wood and bone (or sometimes wood from different types of trees) glued together, with sinew as string, had greater strength – and so farther reach – than the simple bow of the Sumerians and was more accurate. Bertman quotes the historian Yigael Yadin's comment, writing:

The invention of the composite bow with its comparatively long range was as revolutionary in its day, and brought comparable results, as the discovery of gunpowder thousands of years later. (265)

As Sargon improved his weaponry, his opponents tried to match him with their own, as Bertman notes:

Offensive and defensive equipment evolved reciprocally and supported an ongoing arms race: developments in weaponry led to countermeasures in armor, and innovations in armor inspired further advances in weaponry. The introduction of the metal helmet, for example, led to the introduction of a battle-axe with a head like an adze to pierce the helmet's metal shell. (264)

Sargon also moved the heavy chariots further to the rear and relegated them to transport vehicles to keep them from interfering in troop movements and because he no longer needed the mobile armories as he had his new bow, and the archers carried their own arrows. Slingers created their own projectiles from the abundant clay outside any Mesopotamian city, forming them into 'bullets' that could be fired from the sling with substantial accuracy and speed. Some of these, recovered from sites in the modern day, show how they were not fully dried when used in battle as trace materials had adhered to them, as opposed to fully dried 'bullets' which have no such additions.

The Akkadian army also traveled with scribes who were responsible for calculating the amount of force to take down a city wall or how much earth was needed to build an offensive ramp up a battlement. Scribes also calculated the number of prisoners taken and noted what was done with them, as in which of them were sold as slaves, kept by generals, or executed. With this army, Sargon conquered Mesopotamia, securing the trade routes and centers of production, as Eannatum had done earlier, only on a much larger scale.

Ur III & Babylonian Conquest

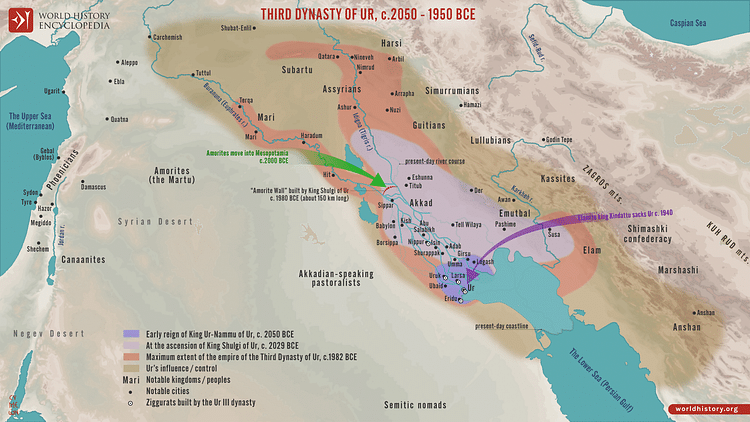

The Akkadian Empire declined and fell to the Gutians who were defeated and driven from the region by the Sumerian kings of the Ur III Period (2047-1750 BCE). Ur-Nammu (r. 2047-2030 BCE) associated himself directly with Sargon and his successors, but as a kinder and more fatherly version of the Akkadian kings. His son, Shulgi of Ur (r. 2029-1982 BCE), seems to have drawn on Sargon's military model to defeat the Gutians but, like his father, encouraged a gentler image of the monarchy than the Akkadians had. The literary poetic cycle, Matter of Aratta, written during the Ur III Period, presents a vision of non-violent resolutions to political conflicts.

By the 20th century BCE, the Amorites had established themselves in the region, ruling important trade and cultural centers including Babylon. The Amorite king Hammurabi (r. 1792-1750 BCE) also drew on Sargon's military model. When he first came to power, he quietly trained a professional fighting force and allied with Larsa to defeat the Elamites. As soon as the Elamite threat was neutralized, he turned on Larsa, took from it the cities of Uruk and Isin by allying himself with Larsa's rivals, including Lagash and Nippur, conquered them afterwards, and then took Lagash. By this process, he subdued all the city-states of Mesopotamia and ruled from Babylon.

Hammurabi perfected a tactic for taking cities used by his father, Sin-Muballit (r. 1812-1793 BCE), of either damming up the water supply of the city until it surrendered or, when circumstances suggested it, damming the water and then releasing it suddenly to flood the city just prior to his attack. This tactic proved effective, and, after his conquest of the region, Hammurabi ruled effectively, issuing his famous laws, the Code of Hammurabi, and rebuilding or improving upon what he had damaged or destroyed.

Assyrian Empire

Hammurabi's empire barely outlived him and was then taken by the Kassites c. 1595 to c. 1155 BCE. The Hittites, by that time, already held significant cities and controlled most of the region between 1700 and 1200 BCE, also using a professionally trained army that drew on the Babylonian model. Their king Suppiluliuma I (r. 1344-1322 BCE) conquered the Kingdom of Mitanni which had held the Assyrians as vassals, and, with Mitanni power broken, the Assyrians under Adad Nirari I (r. c. 1307-1275 BCE), asserted themselves and established the Assyrian Empire.

Tukulti-Ninurta I (r. c. 1244-1208 BCE) defeated the Hittites at the Battle of Nihriya in c. 1245 BCE and, that same year, sacked Babylon, using the plundered wealth to fill the Assyrian treasury. Although he was later assassinated for the sacrilege, as Babylon was considered a holy city, the wealth accrued helped fund the military and enabled the later success of Tiglath Pileser I (r. c. 1115-1076 BCE) who revitalized the economy and improved the military.

The Assyrian Empire expanded through military conquest and, by the time of Ashurnasirpal II (r. 884-859 BCE), they had perfected the art of the siege in taking cities. Scholar Simon Anglim writes:

More than anything else, the Assyrian army excelled at siege warfare, and was probably the first force to carry a separate corps of engineers…Assault was their principal tactic against the heavily fortified cities of the Near East. They developed a great variety of methods for breaching enemy walls: sappers were employed to undermine walls or to light fires underneath wooden gates, and ramps were thrown up to allow men to go over the ramparts or to attempt a breach on the upper section of wall where it was the least thick. Mobile ladders allowed attackers to cross moats and quickly assault any point in defenses. These operations were covered by masses of archers, who were the core of the infantry. But the pride of the Assyrian siege train were their engines. These were multistoried wooden towers with four wheels and a turret on top and one, or at times two, battering rams at the base. (186)

The Assyrians perfected the art of war and continued the tradition of justifying conflict as the will of the gods. Eannatum had invoked Ninurta, Sargon called on Inanna/Ishtar, Hammurabi claimed the great god Marduk as his commander, and the Assyrians elevated their god Ashur (Assur) to an almost monotheistic level of supremacy as the leader of their troops. When Sargon II (r. 722-705 BCE) of the Neo-Assyrian Empire defeated Urartu in 714 BCE, against all odds, he took no credit for the victory but attributed it to Ashur.

Conclusion

The Neo-Assyrian empire fell in 612 BCE to a coalition of Babylonians, Medes, and Persians, and, afterwards, the Persian king Cyrus II (Cyrus the Great, r. c. 550-530 BCE) established the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE), which, again using a professionally trained army, conquered a larger expanse than even the Assyrians had managed. Alexander the Great toppled the Achaemenid Empire, which, after Alexander's death, was replaced by the Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE), which gave way to the Parthian Empire (247 BCE-224 CE), which fell to the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE). Although there were significant reforms along the way, including the much faster and more mobile two-wheeled chariot, the paradigm of all these armies was based on the one first established by Sargon of Akkad.

The Sassanian Empire fell to the invading Muslim Arabs who also invoked a deity to justify their conquest. The claim that a god is on one's side in a military campaign has been made by many leaders over the centuries and continues, in one form or another, into the present day. Each time, the claim is presented as self-evidently true and completely novel when, actually, it is only a repetition of a justification for violence and bloodshed going back over 4,000 years.