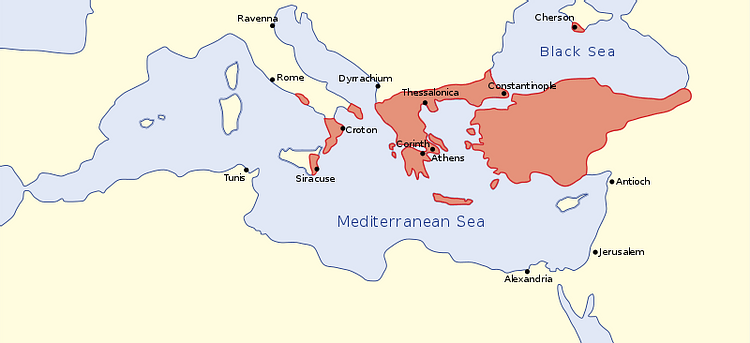

Michael II the Amorion, also known as Michael “the Stammerer”, was emperor of the Byzantine Empire between 820 and 829 CE. He founded the short-lived Amorion dynasty, named after his hometown in Phrygia, which would last until 867 CE. Surviving the major rebellion and siege of Constantinople led by Thomas the Slav, the emperor's reign witnessed little else of success as the empire continued to crumble at its edges, with Sicily and Crete being notable losses.

Succession

Michael hailed from the strategically important city of Amorion (aka Amorium) in Phrygia, the capital of the military province of Anatolikon. Amorion protected the road from the Cilician Gates to the Byzantine capital Constantinople. Michael was a seasoned military commander in the Byzantine army and is described by the historian J. J. Norwich as "a bluff, unlettered provincial…of humble origins, with an impediment in his speech" (131). Michael rose to become Emperor Leo V the Armenian's (r. 813-820 CE) right-hand man and was given the top job of Commander of the Excubitors, an elite regiment of the palace guard.

Michael wanted rather more, though, and he took his chance and seized the throne in 820 CE in one of the most shameless and shocking episodes of self-promotion the Byzantines had witnessed, and they had seen a good few over the centuries. Michael's supporters did not go for the quiet stab in the back down a dark alley assassination plot but murdered the reigning emperor right in front of the altar of the Hagia Sophia church, and on Christmas day of all days.

Actually, Michael and his supporters had been rather pushed into this dramatic action as he had just been condemned to death by Leo the day before - the novel method of execution decided upon involved tying the victim to an ape and putting the pair into the furnaces which heated the palace baths (quite what the ape had done to deserve his sentence is unclear). Michael, accused of plotting a rebellion and confessing his guilt, had been due to be executed on Christmas Day but Leo was persuaded by his wife Theodosia that such an act was not a particularly appropriate one for that special day and so the sentence was postponed to the day after. The decision was a fateful one, and Michael was saved from this ignominious end by his supporters who disguised themselves as a choir of monks and butchered the emperor. Leo proved not such an easy target, though, and he defended himself, according to legend, with a large metal cross for an hour before finally succumbing to the assassins who lopped off his head.

Michael II was immediately released from his prison and crowned, still wearing his chains around his ankles as no one could find the keys. Meanwhile, Leo's mutilated body was dragged naked around the Hippodrome of Constantinople for public ridicule. Leo's wife and children were exiled to the Princes' Islands where the four sons were subsequently castrated. The Isaurian dynasty, which had had eight emperors, one empress, and ruled since 717 CE, was swept away, and the Amorion dynasty begun.

Thomas the Slav

Fortunately, Michael benefitted from Leo V's defeat of the Bulgars in 814 CE and the sudden death of their leader, the Khan Krum. A 30-year peace allowed both the Bulgars and Byzantines to concentrate on other threats. Unfortunately, though, almost immediately, Michael had to defend his throne against a rival usurper, the fellow general Thomas the Slav (although actually from Gaziura in Asia Minor). Rallying support from those outraged at Leo V's murder and backed by all but two of the provinces (themes) in Asia Minor, Thomas led a damaging three-year rebellion against Michael's regime.

The charming and wily Thomas made sure he appealed to just about every group who might have a grievance against the emperor - the overtaxed poor, those in the Church who opposed Michael's (albeit moderate) stance against the veneration of icons in the Byzantine Church, and even those old followers of the deposed Constantine VI (r. 780-797 CE) - bizarrely, Thomas even claimed to actually be the blinded Constantine VI and had himself crowned as such in Antioch. Thomas, unknown to the majority of his followers, was actually receiving cash from the Caliph Mamun (r. 813-833 CE) and in return, he would probably have turned Constantinople into a fiefdom of the Abbasid Caliphate.

Crucially, Thomas could also call on the naval fleet of the province of Kibyrrhaiotai, located along the southern coast of Asia Minor, and the height of the crisis came when Thomas besieged Constantinople from the sea in December 821 CE. Heavy winter storms saw off the initial attacks, and then, in the longer term, the massive fortifications of the city, the Theodosian Walls, and the judicious placement of catapults and mangonels ensured the capital resisted Thomas' own catapults and siege engines.

The emperor was also fortunate to have the Bulgar Khan Omurtag (r. 814-831 CE) as an ally. Omurtag's army helped to finally break the stalemate and end the siege in March 823 CE. Thomas' army was crushed on the plain of Keduktos near Heraclea and swept up by Michael's force riding out from the capital. Thomas fled the scene and, with a mere handful of followers, barricaded himself in the fortified town of Arcadiopolis. Michael pursued his foe and laid siege to the town, nicely reversing the roles of attacker and defender. Thomas held out for a few months, but he and his men were forced to eat their own horses to survive. Finally, in October 823 CE, Michael offered a pardon to the defenders if Thomas was handed over. Thus, the would-be usurper was captured and executed, first having his feet and hands cut off and then his body impaled on a stake.

The Eroding Empire

Michael might have survived a siege at home and put down the greatest rebellion the Byzantine Empire had ever witnessed but farther afield events were anything but encouraging. There were significant defeats at the hands of the Arabs in both Crete and Sicily in 825 CE and 827 CE respectively. Crete, in particular, became a major problem for just about everyone in the Mediterranean as it turned into an impregnable base for pirates, while the city of Candia (Heraklion) developed into the biggest slave market in the region. Michael launched three separate attacks on the island between 827 and 829 CE but all failed to retake it. The loss of parts of Sicily would also have significant repercussions as the Arabs used it, like so many armies before and after them, as a landing stage to attack and conquer southern Italy.

Relationship with the Church

Michael had been only a moderate iconoclast who did not take very much interest in the debate which some of his predecessors had fuelled by their persecution of those who venerated icons. He even pardoned such notable iconophiles as Theodore of Studium, and his moderate policies generally made him popular with both sides of the debate. One area which did ruffle some ecclesiastical feathers was the emperor's second marriage. As an important representative of the Church, the ruler was not meant to remarry, but after Michael's first wife Thecla died, he married Euphrosyne, the daughter of Constantine VI. To make matters worse, Euphrosyne was a nun. Nevertheless, Michael managed to get around the Church and the past vows of his betrothed to marry his new sweetheart, who, with her royal blood, also gave his reign and, more importantly, his heir, an air of legitimacy.

Death & Successor

Michael died of natural cause in October 829 CE and he was succeeded by his son Theophilos (r. 829-842 CE), then aged just 25. It was Theophilos who would continue where Leo V had left off to vehemently continue the destruction of icons in the Church and the persecution of those who venerated them. Theophilos was succeeded by his son Michael III (r. 842-867 CE), the last of the Amorion emperors whose early reign was dominated by his regent mother Theodora.